Of the musicians I’ve interviewed, only a very few have shown a true interest in visual art. Don’t know if that observation can be generalized, but it’s however safer to guess that it would be much harder to find a visual artist who’d be entirely indifferent about music, personally or artistically. Interest in music is more universal in this sense.

Not all visual artists like music to the same degree, or in the same manner, of course. Some use music on the background while painting (Pollock, for instance), some listen to music only when they’re not painting. Some artists (eg. Kandinsky) theorize about music and make music be at the core of their artistic ambitions, some other (this being perhaps the largest sub-group) simply seek inspiration from music in one way or another, in order to get in the mood, and get back to work, and so and so forth. In short, there are countless ways of how visual artists relate their work and life as artists to music, ranging from explanations that are fairly simple and naive, ending up in nobler and more powerful arguments.

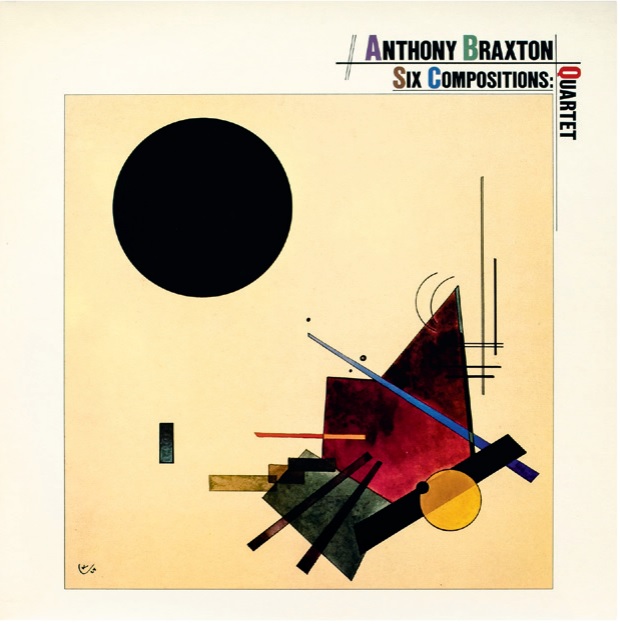

Lars-Gunnar Nordström (1924 – 2014) is an internationally recognized Finnish painter, a master of non-figurative (no representation) abstract art, best known for his precise geometric paintings showing angular and curved flat colour surfaces that form clear, strong, dynamic compositions. Nordström is considered to be one of the leading representatives of Concrete Art in Europa during the second half of the 20th century.

ART & MUSIC

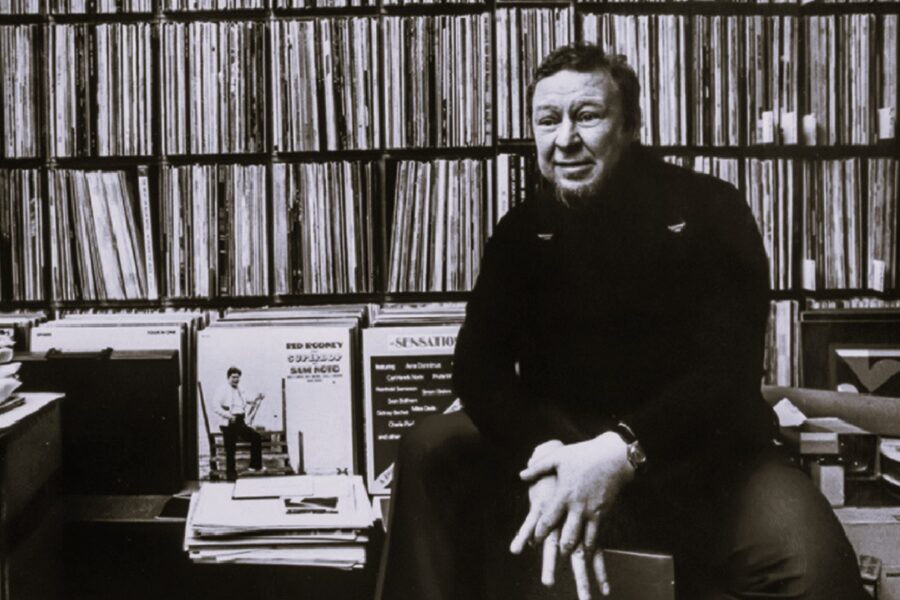

Nordström was also an unrelenting jazz freak. A big one. He was an owner of a substantial record collection, starting from the 1930s and extending up to early 2000. The collection, apart from being one of the largest in Scandinavia, was remarkable also culturally because it told much about how jazz landed in Nordic countries. Was Nordström’s art related to music? And jazz, in particular?

Apart from some obvious, partly figurative painting from the 1950s (see above), more relevant is how music related to his purely abstract paintings. Visual artists sometimes wish to establish a deeper aesthetic and philosophical connection between their work and music, and Nordström was no exception. He would often parallel the two by phrasing that he paints “music for eyes”: “I construct art mathematically, as happens in music, I make music for the eye, it has harmony and rhythm, which are based on the colours’ own innate mechanisms.” On another occasion he described his paintings as having rhythm and chords, the shape giving them a theme. In real life, however, he kept the two completely separate: he would never listen to music while painting or doing other art. Instead, he tried to secure 2-3 hours per day for a more focused exclusive listening to his records. No matter how one looks at it, Nordström attempts to tie together his art and his zeal for jazz, are fairly general and obvious, not based on some systematic art-theoretical thinking. If I’m asked, his art can be perfectly well evaluated in isolation of any reference to music he was listening to.

LOVE OF MUSIC?

Was Nordström a music lover? Or was his vast record collection just a cover story for something deeper? What a question! After all, we’re dealing here a man who devoted much of his adult life in order to be surrounded by jazz, concerts or records. Given his endless enthusiasm, it’s fair to say that he was genuinely sensitive to music (music’s sound), and verifiably able to get fascinated by it. But at the same time he wasn’t a melomane (a true amateur of music), nor took the kind of attitude toward music that eg. musicologists do. His love for music was that of a record collector! Being a record collector is one way of loving music, just like being an audiophile is, both being special ways of being in this world (being a Hi-Fi journalist is yet another). Nordström’s passion for music became concrete, and was manifested in his activity of collecting records. To live on the nerve of music meant, not just listening to it, but making a regular and fervent effort to grow his already substantial record collection. Listening to music was no doubt pleasant but did not provide final fulfillment. His interest in music was perfected and completed through collecting the records.

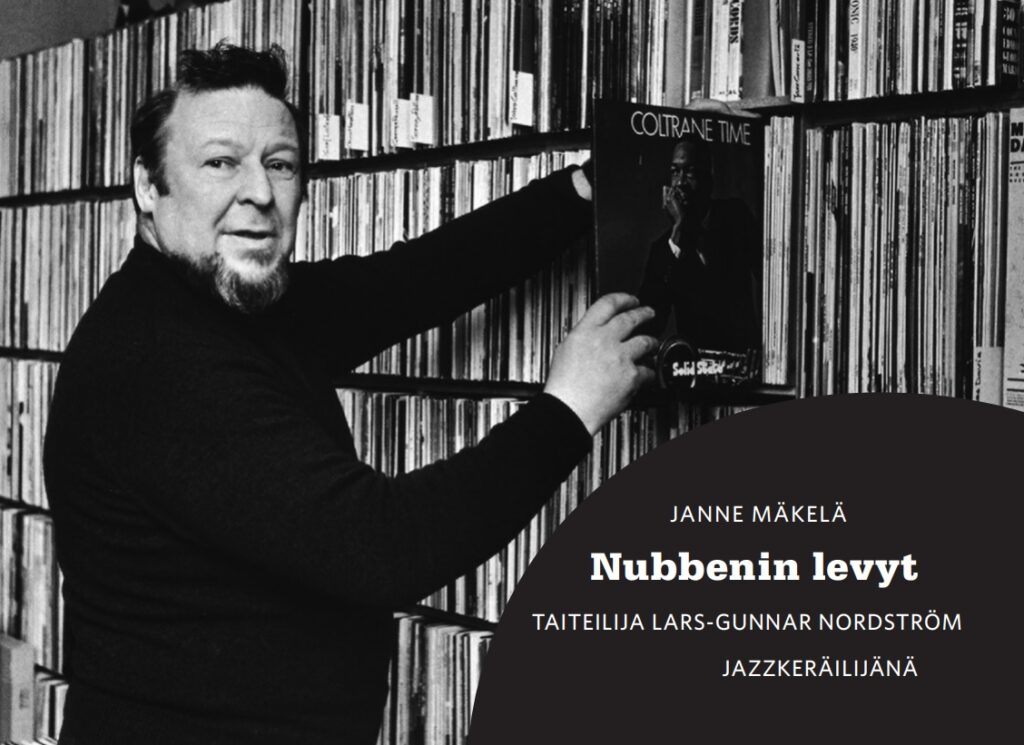

The proof? The proof nicely shines through from the 2019 book by Janne Mäkelä, a researher at the Finnish National Library. In the book, Mäkelä not only to makes sense of Nordström’s vast record collection per se, but also makes an effort to understand what was Nodström’s true driving force. To enter in his head, so to speak. What follows is taken from this excellent book.

Firstly, at some point, it so happened that Nordström bought more records than he had time to listen to even though he had stressed that he buys records only to be able to listen to good music. Well, that happens to everyone, but. There was a time period when Nordström bought loads of LPs without owning a proper playback system for his acquisitions. He still had his gramophone for about 1000 of 78 RPM’s, including many very best and super rare recordings by Ellington, Billey Holiday etc. Seems that while buying more and more LPs he contented himself with listening to his shellacs, the sound quality of which he often complained about, or he might have taken his new LPs to his friends’ place, those who already owned a turntable. Anyway, for 13 years Nordström kept buying LPs without being able to listen to them with a record player! A music lover?

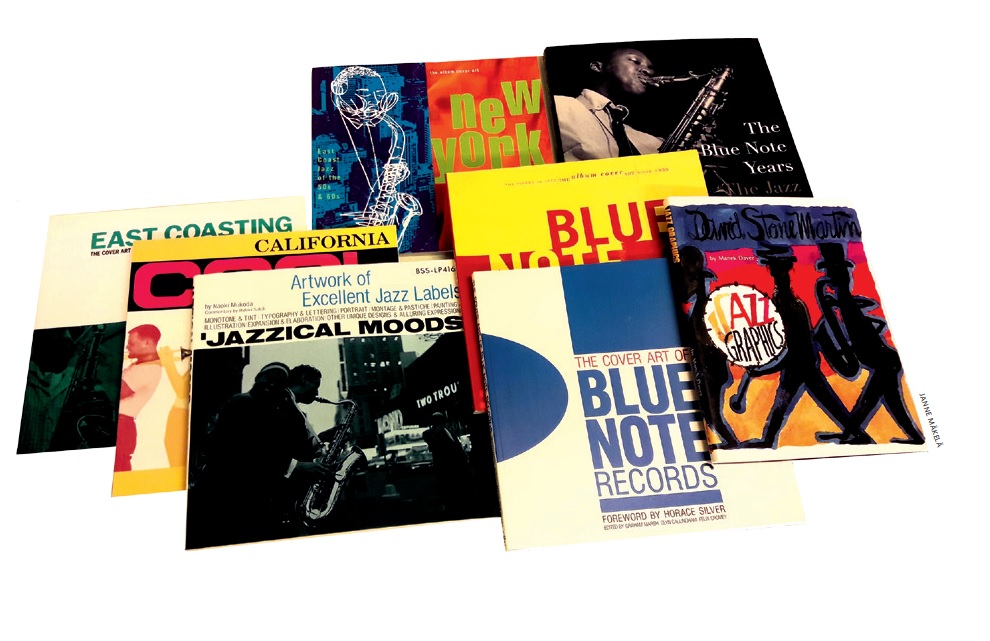

If he did not listen to his growing pile of records, what did he do? Like all true collectors, who primarily approach music through their records, he often preferred to talk about music, jazz especially. And when he did, it was less about the music, and more about records and related stuff based on cover texts and linear notes. By reading LP covers he also learned English, an asset which later turned out to have great value for growing his collection (Nordström’s mother tongue was Swedish). In addition to reading, he liked to watch album covers, their art. In those days, many LP covers, jazz especially, flirted with modern visual art, and that of course didn’t go unnoticed by Nordström. His favourite cover artist was David Stone Martin whom he considered to be one of the greatest of all times. Nordström also owned a number of books on album covers. No doubt, he would have loved to be able to design album covers for his jazz idols.

Nordström is remembered to have been in a constant mood of collecting records. He had those famous ”restless fingers” of true collectors. He was a frequent sight at record shops always carrying a big bag of records back home. At least once, he was nominated as the Record Collector of the Year in Finland. Searching and buying would calm him down, made him relax and feel at home. As the book concludes: “He (Nordström) was definitely mentally dependent on it (collecting), harmlessly perhaps but dependent still. It’s of course hard to say from outside what part of his emotional life Nordström projected to collecting but that it was some tormented unfilled feeling, need not be doubted.” All in all, it is safe to conclude that Nordström’s love for jazz was motivated equally much by the act of collecting records than the music itself. It is only logical then that he didn’t seek fulfillment and abundance, but expectation and imperfection, the felling of getting something that he not yet had gotten.

WAS NORDSTRÖM AN AUDIO NUT?

Eventually Nordström purchased his first real turntable/speaker system, the Braun SK 6, the famous design by Dieter Rams. Technically it meant an advanced pick-up (no more steel or bamboo needles), stepless volume adjustment, tone controls, channel balance control, four speeds (incl. 78 rpm) etc. It was a dream come true. The music sounded much better now, and soon the Braun’s SK 6 became the centerpiece of the house, almost a mythical device that only a few were allowed to touch.

But he wasn’t a Hi-Fi nut as we nowadays understand it. The SK 6 sports two built-in loudspeakers, but it had also the outs for possible separate stereo speakers. It’s nor clear whether Nordström ever acquired separate stereo loudspeakers or not, but if he was listening to the Braun’s internal speakers, he basically kept listening to a mono-sound even from his stereo-LPs, assuming that he wasn’t sitting closer than 1 meter from the SK 6 (ie. near-field). Be as it may, it is arguable that Nordström wasn’t an audiophile in the modern sense, and only cared about the sound quality as most collectors do. Records came first, the sound quality second.

However, Nordström was far from being indifferent about the sound. He much appreciated that the sound of the turntable was better than from his gramophone. He was also among the first to acquire a portable C-cassette player (for copying his shellacs), and also one of the first to get a CD player already in the 1980s. More importantly, he could easily retreat from a live concert and go back home to listen to his records, without no one’s pushing, disturbing, making noise etc. He wanted to hear what’s going in music. As the book explains: “Already in the 1930s, listening to music solo had become an ideal, especially in the field of classic music. A serious music lover was expected to collect his own record library, and, by sitting in an armchair, enjoy the sweet sounds in peace. Later, the same style was adopted in jazz, especially when, from the 1940s onwards, the dance element in jazz began to give way to virtuoso-like playing and artistic ambitions. At the same time, technically much higher quality of sound reproduction spread to homes and created Hi-Fi as a hobby, underlining the bliss of focused home listening.”

THE RECORD COLLECTION

What prompted Nordström’s love for jazz was a mind-blowing experience he had in hearing, for the very first time, Duke Ellington’s Moon Indigo on the radio in 1941. When he years later got hold of the Ellington’s record, it wasn’t on par with the initial experience. (I know people whose first encounter with Billy Holiday has been 78 RPM mono records from the 1930s, and who have never recovered from the experience no matter what LPs they have later heard.) Anyway, it was Ellington’s Moon Indigo that lit a spark to get hold of such records and to start collecting other records from the famous American jazz musicians and bands.

Young Nubben bought his first audio record at the turn of the 1940s. It was Ellington, Blue Harlem published by the American Brunswick company. Other Brunswick records followed, including Count Basie’s 1938-1939 production. Later, it was Louis Armstrong that became one of the main objects for Nordström’s jazz collection (Nordström later claimed that it was Armstrong’s 1949 Helsinki concert that triggered his record collecting hobby). Soon he found Lunceford, Henderson, Webb etc. etc. In the beginning, it was mostly big bands. Then came Coleman Hawkins and Roy Eldridge.

At the time if in Finland one wanted to get hold of certain American jazz records for a reasonable price, there was only one option: travel and buy them. In those days not many people could afford that. However, Nordström was lucky and he was offered visiting USA on two occasions. Those visits increased his collection by several book shelf meters.

Did Nordströn collect records only from male artists? Nope. On the contrary, the collection contains many performances by women, including recordings by Lil Hardin Armstrong and plenty of releases by Bessie Smith and other early blues stars from the 1920s. He loved Billie Holiday, whose recordings he acquired already in the gramophone era. The collection of Holiday’s LPs alone makes 45 pieces, Ella Fitzgerald came with 39 LPs.

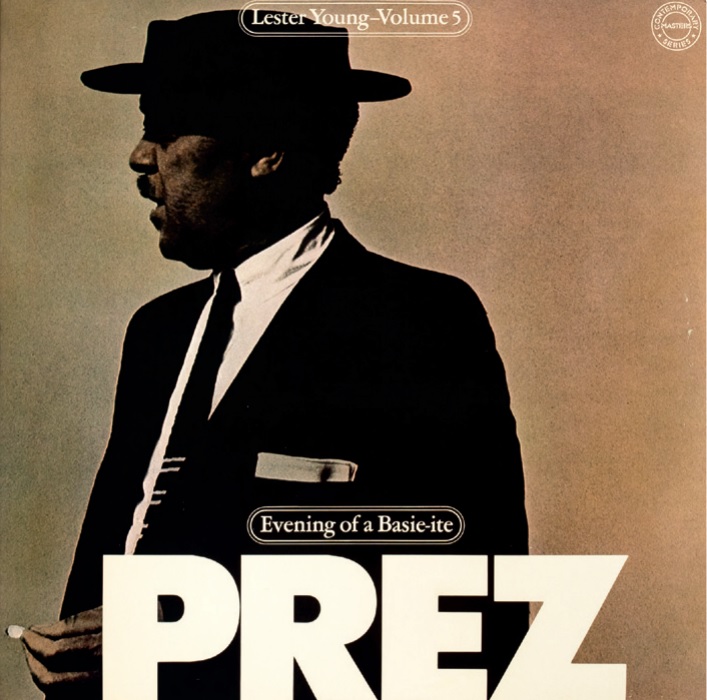

The jazz performed by the blacks was particularly interesting to Nordström. There are hardly any Frank Sinatra or Bing Crosby records in the collection, no romantic “lonely boy” swing records or the cool albums of the late 1950s. Compared to the cool jazz of the saxophonist Lester Young and trumpeter Miles Davis, the stylized cool jazz by Frank Sinatra etc. was too hedonistic for Nordström. However, Nat King Cole, Mel Tormé and Cab Calloway are fairly well represented.

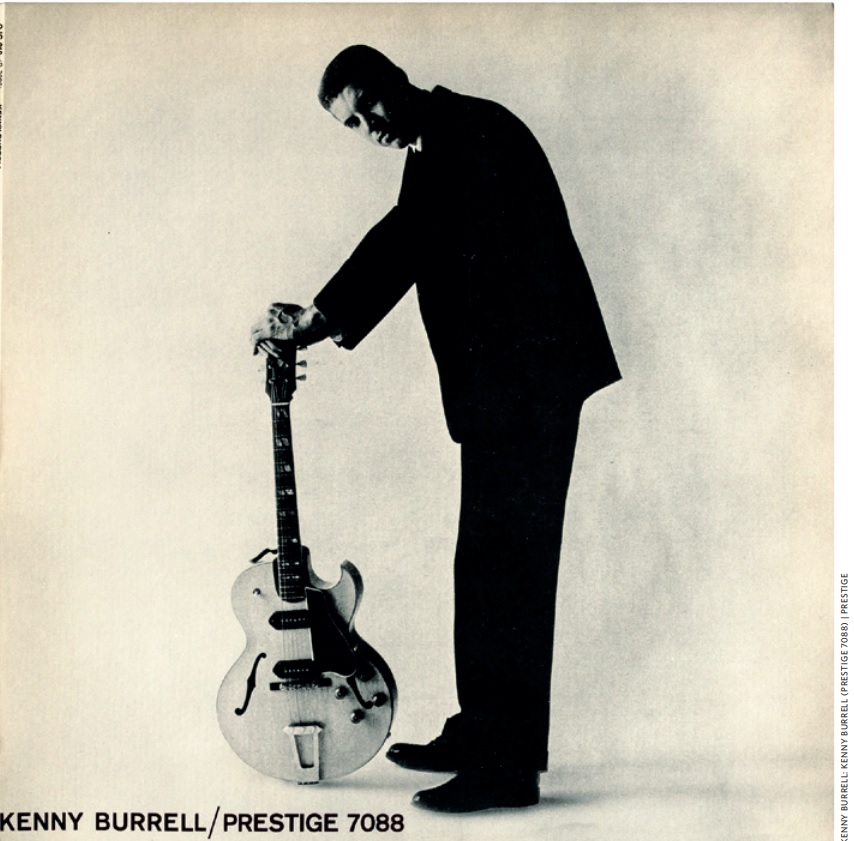

American jazz is well covered as long as it wasn’t “electrified”, which Nordström was suspicious of. In particular, it was the electric bass that sounded foreign to him. The electric organ was fine, and so was electric guitar given it a semi-acoustic one and sounded dry. Wes Montgomery, Kenny Burrell and Grant Green were accepted, as were some later guitarists as long as they were smart enough to stay away from electronic effects and funk rhythms. But no such guitarists as Al DiMeola or John McLaughlin, not even Pat Metheny, and certainly no fusion jazz (eg. Weather Report). The book: Aged between fifty and sixty, Nordström was no longer enthusiastic about new styles. In the 1980s, Wynton and Branford Marsalis could make him happy for a while, because the brass brothers understood elegance and history, even if there was too much electric bass at times.

That American jazz is well represented is no surprise: for Nordström American jazz was the best jazz in the world. Of other, the Danish bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen stands out in the collection thanks to his connection with many legendary American musicians. Swedish jazz is also remarkably well represented. Baritone saxophonist, pianist and composer Lars Gullin is covered by almost twenty LPs, as are older Thore Ehrling’s and Thore Jederby’s recordings from the 1930s. In addition to Nordic jazz, the collection occasionally includes Japanese and Eastern European jazz. The key exception in Nordström’s collection is the Belgian guitarist Django Reinhardt whose albums Nordström had almost forty.

THE COLLECTION IN NUMBERS

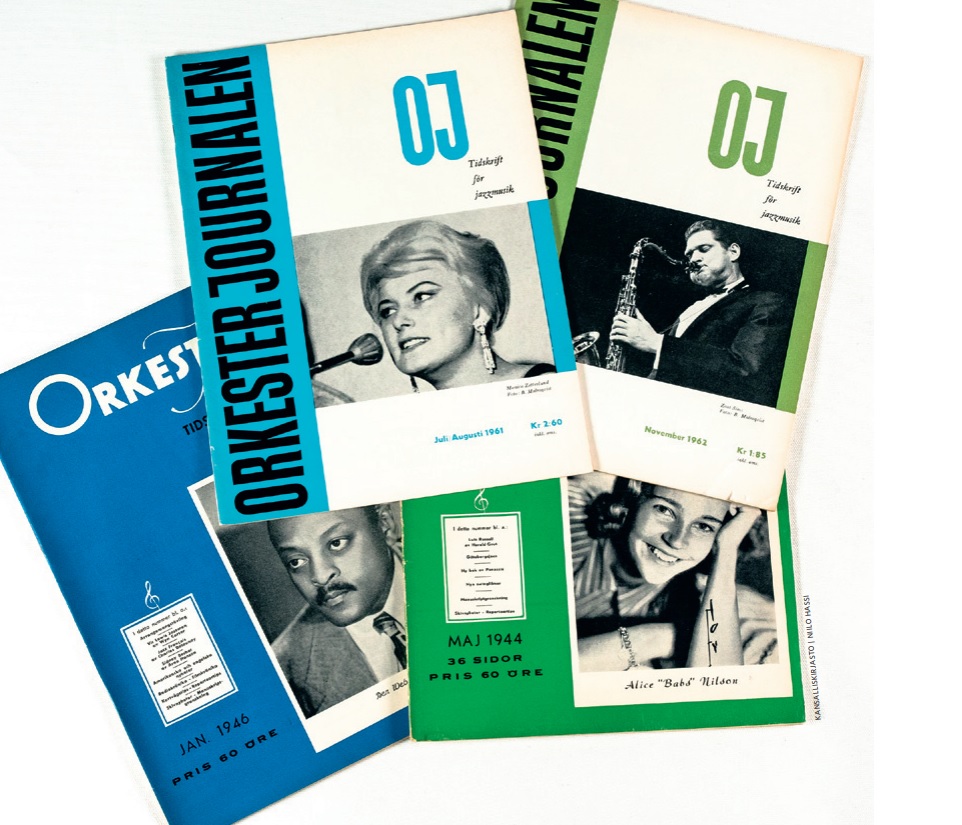

When he stopped collecting records in the early years of 2000, the largest part of the collection consisted of altogether 11,000 LPs, first LPs from the late 1950s onwards, that is, 51 bookshelf meters (c. 220 LPs per meter). On top of that the collection contains just over 1000 pieces 78 RPM shellacs, about 3600 CDs, C-cassettes, video tapes, books, discography, magazines, catalogs, reproduction equipment, etc. Altogether material exist equivalent to over 100 bookshelf meters.

Some sources claim that Nordström’s collection was the largest private collection of jazz records in Finland, and possibly also in the Nordic countries. True or not, it’s a huge collection by any measure. However, more than the exact number of items, what really makes Nordström’s collection unique was the fact that he collected his records over 60 years! And he did not do it by buying large quantities at once but almost one by one. It is for this reason that the collection provides an indebt view of and insight into how jazz, in the form of records, landed in Finland and in Scandinavia from the late 1930s to early 2000. Nordström’s record collection possesses great cultural and historical value.

So how did Nordström collate his vast records? At first the collection was easy to manage, but when it expanded in the 1960s and especially in the 1970s, all systematicity faded. Nordström sorted his albums into different blocks, mainly by artists. Blocks could also be based on other attributes such as genres (eg. boogie-woogie) or regions (eg. Sweden). Like all genuine record collectors, he had no trouble in finding the album he wanted to find, if not otherwise then thanks to the written sticky notes he placed in between the records.

The book

Towards the end of his life Nordström, partly due to his illness, lost his interest in records and listening to music in general. The collection was nearly lost before the Finnish National Library intervened and together with the Nordström Foundation agreed to save it for public interest, and place it in the cellar of the National Library as a uniform unchanged collection, for researchers etc. to study and enjoy. The author of the book, Janne Mäkelä, was hired to sort out the collection and go through all the acquired material starting off from LPs. He did, and as a result of two years of hard work, the book was published in the Series of National Library’s publications (no 85). A book that makes thought-provoking reading also for audiophiles!