From a context to another, it has emerged that for people working in the cultural scene in Pakistan it has not been straightforward to establish contacts with their foreign counterparts. So with India too, although the cultures of India and Pakistan are deeply interconnected. It must be remembered that mutual mistrust and discontinuity is rarely one-sided.

Nevertheless, and as one would guess, from music’s standpoint national borders are transparent. Bollywood productions, for example, are immensely popular on both sides of the border. Building on the ideal that music could once again be a binding force, and a seed for new collaborations, across the South Asian region, the Found Sound Nation, a Brooklyn artist collective and production team, set out to make that happen by bringing together a group of musicians from Pakistan, India, and the U.S. in the spring of 2015 and 2016 for a month-long residency and tour. The venture was called the Dosti Music Project.

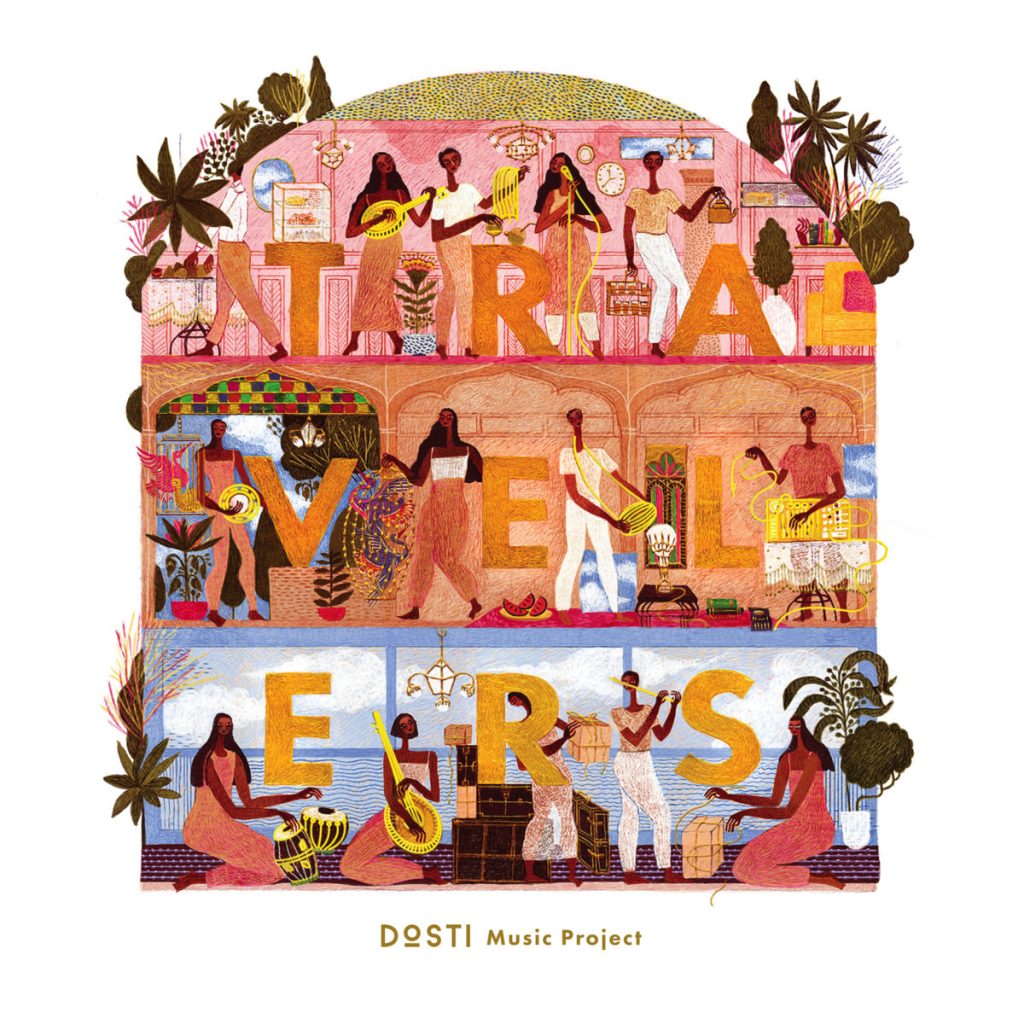

Now the Found Sound Nation has released its first worldwide album: “Travelers: Dosti Music Project”. It’s a compilation of 12 tracks, and accompanying music videos, from the first two years of Dosti. Dosti means friendship in both Urdu and Hindi. The release is a “statement to transcend political and cultural barriers through cross-cultural musical collaboration”.

Artists present on the album included Pakistani experimental electronic artist Slowspin, Virginia born singer/songwriter Abakis, multi-instrumentalist, guitarist Danish Khawaja from Lahore, Pakistan, bass player Darbuka Siva from Chennai, India, horn and accordion player Jeremy Thal from Madison, USA, … and many other talented musicicans from the three countries.

Artists present on the album included Pakistani experimental electronic artist Slowspin, Virginia born singer/songwriter Abakis, multi-instrumentalist, guitarist Danish Khawaja from Lahore, Pakistan, bass player Darbuka Siva from Chennai, India, horn and accordion player Jeremy Thal from Madison, USA, … and many other talented musicicans from the three countries.

Apart from two tracks, all music was collaboratively written and recorded during the residency. “The artists performed original music while reinventing traditional music, and developing initiatives that would make a positive impact on their communities.”

As said, this release had loftier goals than sheer music making, and it should not be ignored while listening to the album. However, the philosophical foundation does not remove the fact that the group has managed to create music that combines a wide variety of musical traditions (Sufi singing fused with indie-rock tendencies, beatmaking and avant-garde jazz are picked up, but which exactly the influences are is not that important), and do it in the way that the unique cross-cultural collaboration is wrapped into a fairly uniform style that traverses and enlightens all the pieces.

If one listens to the music carefully and attentively, one will notice that there are pieces that if taken out of the context, would expose hardly any Asian connotations (inclusion of Western percussion instruments and electric bass speaks for this too), but when offered as part of the Dosti whole, blend beautifully into the Asia-influenced sound world. The variety is refreshing, and despite the music’s apparent superficiality, relative to more sacred traditional music, the ultimate feeling is that the group has not given up for commercialism.

If the project could continue, and the musicians from the three countries let deepen their collaboration in order to reconnect different musical traditions, I’m sure their musical thinking would go on growing and develop into finer and more complex dimensions. But equally important is the way in which the Dosti musicians have “modelled creative, cooperative, and egalitarian cultural exchange” in order to re-link the politically fractured South Asian subcontinent”.

“People-to-people diplomacy” in the most tuneful and encouraging manner.