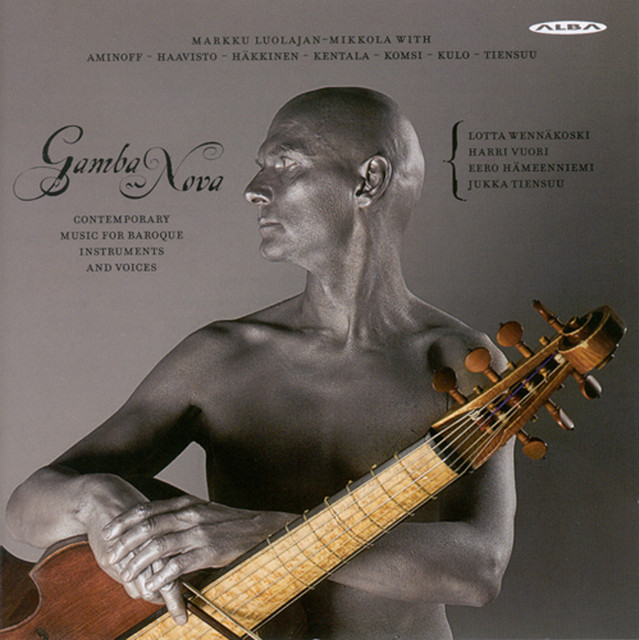

Indian classical music, as well as other Asian music, has attracted Western world composers since ages (well, at least Romanticism onwards), but the interest has mostly stayed on the level of superimposed exotica rather than be a deeply integrated part of the musical language. Not so with Eero Hämeenniemi (born 1951), a Finnish composer, musician and a writer.

Hämeenniemi is a productive composer. He’s written four symphonies, a number of concertos, string quartets, vocal music, music for jazz combos etc., in addition to working for the University of the Arts Helsinki in the capacity of a docent and professor.

India came to Hämeenniemi’s life early on in the 1960s when, according to Hämeenniemi, Karlheinz Stockhausen recommended him Sri Aurobindo’s book Life Divine. He begun to study Indology and Sanskrit at the University of Helsinki.

Having learned some Hindi, he travelled to India in 1984 under a cultural exchange scheme. Soon India became a life-long obsession to Hämeenniemi who regularly spends time in India to participate in local musical events and to make music with a large network of Indian musicians.

No wonder then that Hämeenniemi’s music has been strongly influenced by Southern Indian classical music. The influence can be seen eg. in his appreciation toward improvisation, the techniques largely lost in Western classical music, but which Indian musicians have a natural affinity with. Many of Hämeenniemi’s works contain improvisation elements, even by a whole orchestra.

Hämeenniemi has stated that he’s primarily keen on musicianship – playing, composing, performing, improvising. In India, a composer without being also a performer, the musician, is almost a conceptual impossibility.

When it comes to handling complex rhythms, Hämeenniemi often assigns the job to Indian musicians. When the question is about harmony he calls up Western musicians, “melody and its development being very much the communal ground”. In an interview Hämeenniemi describes how Indian musicians are specifically good at Indian rhythms, meaning that they do not usually play the basic rhythm that do exists, but instead, a number of levels over it.

Hämeenniemi himself often composes at the so-called second rhythmic level. He’s been especially interested in Karnatic rhythms, because of the very important structural role they play in Karnatic music. While in the West, explains Hämeenniemi, rhythm is mainly a way for creating movement, in Karnatic music it can also create structural tension and release as well as a sense of arrival. In Western music harmony is normally used to achieve these ends.

Hämeenniemi collaborates closely with a number of Indian musicians, such as the celebrated singer Bombay Jayashri. In these encounters Hämeenniemi has found that while Western musicians may find it hard to cross the border, Indian musicians – and jazz players for that matter – know at once how to play together. Both are accustomed to “just choose a suitable scale and start playing”. Out of 72 different scales in Southern India, some area readily familiar to jazz players.

Even though South Indian influences are clearly present in the music of Hämeenniemi, he denies that he would be doing so called fusion music, an Indian bit here and a Western bit there. The question is not about having a mixture of two different musical cultures, but rather art in which “both spread out in an infinite number of directions”. “There is no country on the map where people make this sort of music. You couldn’t create music like this by mixing, because music reflects the personalities of all the musicians involved in making it.”, has Hämeenniemi said.

Apart from making music with South Indian influences, Hämeenniemi has written three books about South Indian music culture, as well as translated Tamil poetry into Finnish.