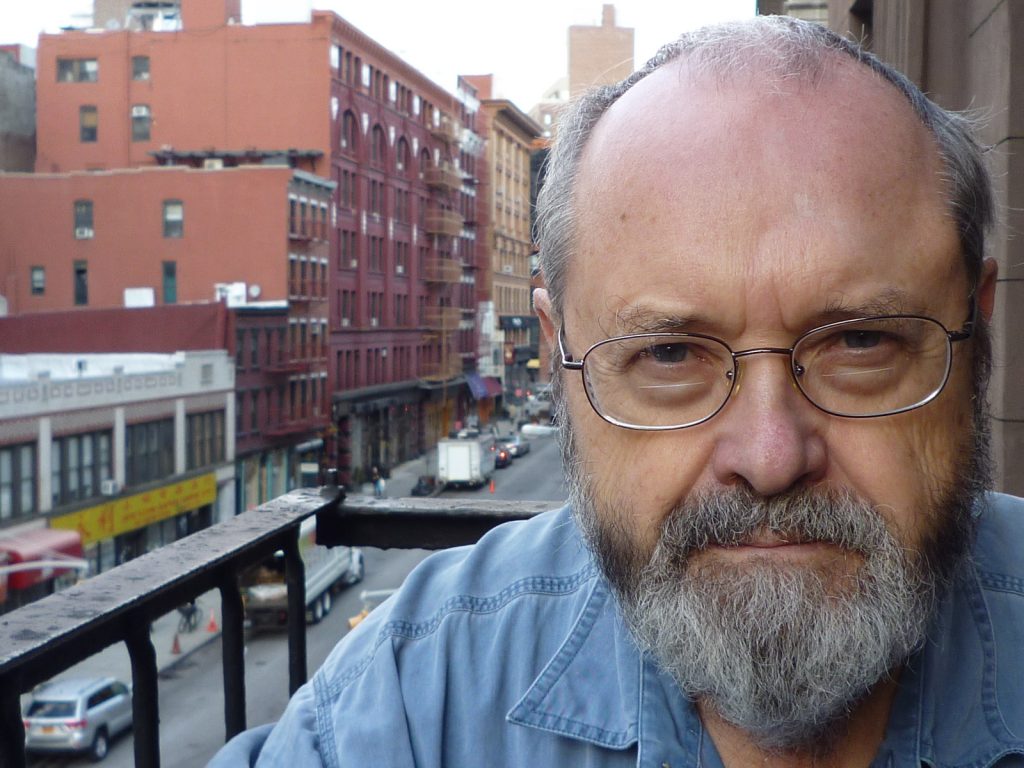

It was not until the last decade that Phill Niblock (b. 1933), the pioneer of minimalism and drone music, became more widely known as an influential film/video artist and composer.

His special interest is in compositions that focus on one acoustic instrument at the time. He would typically record the exact sound frequencies (tones, not notes) one by one. The signal is then routed to a machine in order to enable Niblock accurately define, to tune, the correct tone. The instrument player must not play vibrato.

When the individual long tones, only very slightly distinct in pitch, are combined into one as layers, a wholly new sound, according to a plan, is created, including also combinatorial sounds (complex overtone patterns) not present in the original tones, creating fascinating psychoacoustic effects.

Thus, Niblock’s highly original and distinctive music is characterized by a constant tension between static surface textures and very active harmonic movements, not unlike with early drone-based minimalism. Niblock’s signature sound is filled with microtones of instrumental timbres that generate many other tones where the performance takes place.

About his early influences, Niblock remembers Morton Feldman’s concert in 1961, and how he was fascinated about Feldman’s new composition entitled Durations and its long tones. He was interested about this composition that did not have melodic structure, rhythm, or harmonic progression. Niblock got the idea that he could possibly make music.

In 1968, seven years after Feldman premiered his piece, Niblock began composing and created his first compositions and the first intermedia performance Environment. During the same year, in 1968, Experimental Intermedia Foundation was founded and Niblock moved into spacious loft at Centre Street in New York, where he has arranged concerts and events regularly since 1973.

In the early phase of his career, Niblock did his music with multitrack tape machines, overdubbing unprocessed recorded tuned long tones, but later he begun to work using computer technology.

In the unpublished interview below, Phill Niblock explains Inner his compositional techniques, early intermedia works, also things that are systematically misunderstood in the literature (eg. cutting out attacks). He also explains how in live performances musicians, wandering through the audience, play their part changing the sound texture through reinforcement of or interference with the existing tunings. These performances are simultaneously accompanied by Niblock’s films and videos.

Internationally awarded Niblock currently directs the Experimental Intermedia Foundation (a foundation for avant-garde music and intermedia art) in New York, whose artist-member he’s been since 1968. In 1993, he opened a branch with window gallery in Ghent, Belgium.

In 2014, Niblock was honoured with the prestigious Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award. Year before his diverse artistic career was the subject of a retrospective realised in partnership between Circuit (Contemporary Art Centre Lausanne) and Musée de l’Elysée.

The interview

Inner: In the late 60s you started making music, and I think your first piece (1968) was realized with an organ. Did you play the piece by yourself?

PN: Yes, I played myself, and the piece gets its driving from its micro-tonality by using different stops of the organ (of Judson Church), because they were never quite tuned the same, so there was some beating and stuff like that going on.

Inner: But what’s the story behind the first piece?

PN: Well I was interested to make music, which had long duration and which didn’t have rhythm or melody in the traditional sense, or traditional harmonic structure for that matter. I was interested specifically to work with the idea of the microtonal intervals that cause different tense. I later recorded instruments in a studio, but I would record each instrument separately, and since nobody was tuning – it was time before tuning meters and stuff like – I got micro-tone intervals just because people weren’t in tune with each other. So when they played ‘A’, it wasn’t 440 Hz but something else. Those early pieces were multitrack, using actually one of the first 16 track Ampex multitrack recorders based on the Ampex 2 inch quad video machines. 1)

Inner: But then there was a change. You went from photography to music?

PN: Well it wasn’t a change but simply an addition.

Inner: But you did do photography for many years?

PN: Well, not so many. I started to do photography in 1960. I never studied anything, so I did everything myself including printing. I can explain how I got started. I begun to photograph lot of jazz people in 1961, 62, 63 … , and then for a short time, I also did some commercial and freelance stuff, but very little actually, before I begun to photograph other things like some theatre people, and started to be much more in the art scene of NY. There I met people who were around jazz and dance theatre. I begun to work with Elaine Summers (1925 – 2014) 2) who just had a very big concert at Judson (Judson Church in Greenwich Village) that I missed, actually. Which was an intermedia event, with film and dance and music. People like Phil Corner and Malcolm Goldstein were doing music with her for that piece (Fantastic Gardens, 1964). So I begun to work with her to do film. 3)

At the same time I had done a lot of photographs, and met this guy (Norbert Kleber) who had the only photography gallery in New York at the time, showing only photographs, so I had a one-man-show in that gallery (Underground Gallery, at 51 E. 10th Street in New York) in early-1966, but after that I sort of stopped doing black and white photography, because I was working, as a day job, for a publishing house, and I was going out a lot of night to see performances and so on, so I simply couldn’t support all the kind of work I was doing.

I also, about that time, was beginning to work on some interactive installation things – sound being generated by images and changed by images – so there were fairly complicated but also simple things, as I was working with simple materials, the setup being quite interesting though. But I couldn’t support all that time either, so I eventually wanted to do this first intermedia concert or event. I had to concentrate and start working more on film by itself and music. It was for that concert (1968) I made that first piece of music. 4)

One of the pieces of the concert was a collaboration with Max Neuhaus and I found it very difficult to collaborate and specifically with Max.

Inner: Max Neuhaus was a percussionist?

PN: He was a percussion player before, but at that time he was beginning to work with the feedback and noise. In fact he was one of the very first real noise guys, you know, he was using very noisy feedback.

Inner: How did you find your loft in Soho?

PN: At the time (1968), I was living in a very small apartment and started living with someone more readily, and we wanted both to move to a bigger space. I was really interested to come to a big industrial space, and it was time when that kind of industrial space could be found from an industrial area, which later became to be known as Soho. It was full of little shops that had machines and stuff like that. So there were big former industrial spaces, but for the most part, for that kind of company that occupied the space, the space wasn’t big enough or the rent was too high or something, so they were moving out to Brooklyn or to New Jersey. So there were empty spaces and they were great for artists to go in. For example, my space was ten meters wide, by twenty meters long and 5 meters ceiling, so it was an immense space for a new yorker.

Inner: Being in New York the spaces must have been very expensive?

PN: No, it was very cheap because companies were moving out, and the landlords couldn’t find anybody to rent the spaces out, basically no company wanted them. The first space I rented was 225 dollars per month, and even then it was cheap.

Inner: Plus, you probably didn’t have any problems with the neighbors?

PN: No, not for me. It was an industrial building and it stayed industrial. Most of the buildings in Soho were taken over, either bought and sold off, apartment or lot by lot, to people who had money. But there were a few buildings that artists moved into and co-operated, so that the artists owned the building, and the famous Fluxus artist and the originator of Fluxus, George Maciunas was behind many of those early buildings, converting them to artist spaces. But they were relatively few and most of the Soho became suddenly a place for doctors and stockbrokers and people like that who moved in.

So I begun doing concerts, because I had a sound system from my own work. I begun to do concerts in 1973, five years after I moved in, and to invite people to come and play, first rather informally, you know. We would call people, and have a small mailing list and send our postcards, and eventually it got funded within two or three years, and we began to do more formal announcements and some advertising. By the late seventies we were doing a lot of concerts, 35 to 50 a year, they were easy, informal, people came in … One might see a different audience in every concert because people would come who knew the person whose concert it was, and they were always called either concerts by composers or intermedia events, so it was based on the work of one composer or occasionally two collaborators. It wasn’t about performers.

Inner: What kind of differences were there between downtown and uptown music scenes?

PN: What differentiates the downtown scene from the uptown, more academic scene in NY, is that the uptown scene is one of ensembles, and the ensemble is fixed and the directors choose the composers and they play the works of 4 to 6 composers, and the ensembles are usually fixed instrumentations, sometimes guests, but basically it is the set ensemble that is playing, and they’re playing essentially more academic music, like music from Juilliard or music schools or older composers who were very well known, and classical music. It was definitely a classical music scene.

Whereas the downtown stuff, sometimes it was obviously classical music, but more often it was some other variant of electronics or improvising or something like that happening.

Inner: If I recall correctly, you didn’t like to make records?

PN: One of the reasons I didn’t like records was because I was interested in the way the music sounded in a performance situation where I had a relatively decent speakers, and that was the way music should sound. So to send the music out to somebody’s tiny hifi system played with low volume, was not the music I wanted, so it was difficult for me to make records.

Inner: Working with the tape machines, what kind of techniques or methods you used? You cut out the attacks of the instrument sounds, but did you change the speed of the tape or use EQ?

Phill: I didn’t use EQ except much later in the mid-80s. With one piece I did use the change in speed which I can describe, but otherwise I didn’t change the speed. I didn’t for the most part have a recorder that could change the speed, as I was using a Revox or later techniques which didn’t have any pitch control.

No, it was quite straight uses of the material, and about the attacks: at the very beginning I did cut out attacks and the trail outs, but I stopped doing that, and yet somehow that has remained in the literature that I cut out the attacks, because of some reviews or like, and all of the pieces which that was mentioned as being what I did, I didn’t do it. I actually let the note trail off and cut out the breathing space, it was a wind instrument, and then the attack begins, so I moved the two together, but with a short space in between, that was the idea. So the note trails off and begins again like in a quarter of the second or less but in a very natural way, so the truth is that I did not cut out the attacks, and I like to go on record right now as saying, “No, I didn’t cut out the attacks” … ha, ha …

Inner: Can you tell more about your practical work with musicians?

PN: There are two times and two places where I work with musicians. One is to record material to make a piece, that’s one situation, the other is for live performances where the musicians were playing with a recorded part of the piece, making additional live sounds with the piece. In the first case, I would normally in the days of a multitrack tape, go with a decision of what pitches I wanted to play to use in a piece, so I would go to the studio, recording a musician tuned precisely to play those pitches, normally tuned by my having a sinewave generator and a frequency counter, so I could dial in exactly to the pitch I wanted, to one hundredth of a hertz, not one hertz or one tenth, but a hundred of a hertz, so I had a very exact pitch, and I would feed that to an oscilloscope and the microphone, and when the musician played, exactly in tune, it was a stable pattern, and if he was flat, it would start to rotate in one direction, and if he was sharp, it would rotate to another direction, so he could see as it begun to rotate that his pitch was varying. That’s how I can record then the whole string of notes of a calibrated pitch, and every ten loads I might end up with two minutes of material of one very specific pitch, and then go on to the next pitch. I might record like a dozen or fifteen pitches in one session.

Inner: During the recording session you didn’t want have any vibration to the sound. The sound had to be a steady sound?

PN: It’s very steady … and single! So that the placing of the tones on the tape, to make the multitrack, is the combination, which makes the difference tones, which is as if we work with a stereo and have tones that are very close together in pitch on different channels, so the effect is that they were in made in space rather than in electronics of the tape.

For example, in A Trombone Piece (1977), it’s three octaves of A’s, and sharp A’s, and so the lower octave was 55 Hz and then 57, 59, 61, and the octave above that was 110, 113, 116, 119, and the octave above that was 220, 224, 228, (232) … a 4 Hz difference, but when you sounded the 57 Hz against 113 Hz, it was only one Hz difference. In the performance situations, normally the musicians aren’t tuned, occasionally they are but not normally, and they listen to the recording and play notes that are close together in pitch but slightly off in the mass of sounds, and usually the mass of sounds is like a lot of pitches anyway. So they create different set of difference notes particularly around them. They frequently wander around the room, and when they’re standing in one place, the people who are around them are hearing something different than the people who’re on the side of the room.

Inner: The films you made in the 60s, what kind of films were they?

PN: There were six films that I finished 5), 16mm films with sound tracks, by 1970. There was some experimental film-like techniques and some time-lapse stuff etc. The material that I used in those days was more nature stuff. In the first piece there was a good mixture of nature and some other things. By the time I made the second intermedia event, it was very much nature material that was driving it, and the third one was really releasing that material, I think.

Then I had trouble because I was using live dance things in these concerts and events, and it was so difficult doing the whole setup and having the dancers and having to deal with the dancers and trying to get gigs and stuff that I decided I wouldn’t work with dancers, and I was looking for substitute material for the film material to use. I then started to do these series of things which look as The Movement of People Working (1973 – 1985), and that became the material, and I assumed that I would do what I did with the other stuff, namely that I will work for three years, and then do something else, but in fact it was so perfect for me that I simply continued to work for 18 years using and shooting that material.

The music has always been pretty much absolutely separate, there’s no temporal or particular aesthetic link between the two. They are intended to be separate entities, and not directly related, or to have to be synced in any way so that in a typical concert I show at least two images and I play music, but the order of the music, the pieces that I play, can be totally different.

Inner: Thanks Phill for the interview!

1. In 1967 Ampex introduced the world’s first 16-track professional tape recorder put into mass-production).

2. Elaine Summers was a founding member of the Judson Dance Theater in 1962 and founder of Experimental Intermedia Foundation in late-1968.

3. With Summers, Niblock created films connected with the performances.

4. The first intermedia performances, which included music, film, and dance, came in December 1968 in Judson Church. There were four altogether, the last one took place in 1972. Niblock called them “Environments.” Later Niblock digitized the archive materials of these events and at Tate Modern in 2017 he screened the films from the last two Environments under the title 100 Mile Radius (Environment III) and T H I R (aka Ten Hundred Inch Radii) (Environments IV).

5. Morning (1966-1969) from an idea by Phill Niblock and Jean Claude Van Itallie, filmed by PN, text by Lee Worley and Michael Corner, with members of the Open Theater group. Starring Lee Worley, James Barbosa, Cynthis Harris, Sharon Gans, Joseph Chaikin; text read by Lee Worley, James Barbosa, Barbara Porte, Dorothy Lyman, Michael Corner. Black & white 16mm film.

The Magic Sun (1966-1968) with members of the Sun Ra Arkestra, music by Sun Ra and the Arkestra. Filmed on high-contrast black & white 16mm film.

Dog Track (1969) — a film by Phill Niblock, with a found text read by Barbara Porte. Color 16mm film.

Annie (1968) — a portrait of the dancer Ann Danoff, with a sound collage soundtrack. Color 16mm film.

Max (1966-1968) — an image collage film/portrait of percussionist/sound-artist Max Neuhaus, with a collage soundtrack by Max Neuhaus. Black & white 16mm film.

Raoul (1968-1969) — a portrait of the painter Raoul Middleman, with extensive use of time-lapse film technique. The soundtrack is improvised by Raoul Middleman and Phill Niblock. Color 16mm film.