Imagine being in the countryside early in the morning and opening the window of your room. Birds singing, the sound of a stream, your neighbour chopping wood. Many other sounds and noises can suddenly happen, just use a little imagination. Voilà! What if this landscape replaces an orchestra that could play you a welcome tribute in the morning? But how could the natural soundscape perform tuned frequencies that are perfectly timed as on a musical score? How can a chance occurrence of sounds that express themselves freely in these surroundings coincide with an orderly and codified system of notes that runs parallel in real time?

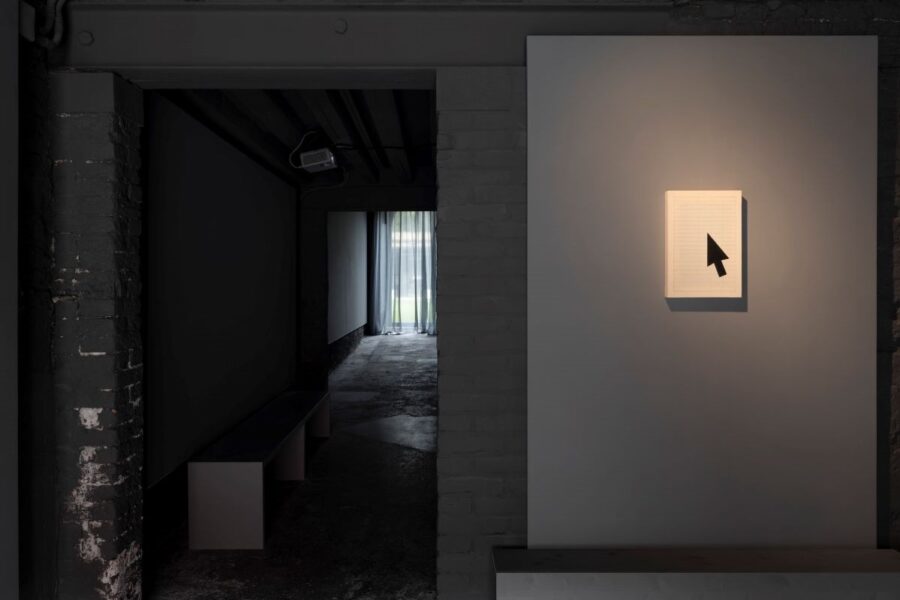

The opening image above: Installation View. Alessio de Girolamo: Real Time. Capsule Venice, Venice, Italy. Ph. Andrea Rossetti. Courtesy of the Artist and Capsule.

Real Time, software implemented by the Italian artist Alessio de Girolamo (b. 1980, Sanremo, Italy; currently lives and works in Lecce, Italy) in collaboration with LIM – Laboratorio di Informatica Musicale (Music Informatics Laboratory) at the Università degli Studi di Milano, answers these questions. Developed over several years, Real Time represents a significant breakthrough in the way that a musical composition is conceived. It uses the elements of the natural soundscape that are closest to the notes of a chosen musical score – without any pre-sampling or pitch alteration – to create a brand-new score in which the natural and the artificial meet, and inevitably clash. This software replaces the “silenced notes” in the original track with the closest acoustic frequencies. Real Time highlights the breach between the spontaneous, non-numeric, circular, and aleatoric patterns followed by a soundscape and the time-based, numerical logic of traditional musical composition that result from a composer’s awareness and intention. The software thus represents an (occasionally impossible) attempt to reconcile these two contrary systems.

Real Time is also the title of Alessio de Girolamo’s most recent solo exhibition, which was presented on the premises of Capsule Venice concurrently with Biennale Musica (2024), when the artist unveiled his most recent audio and video experiments using the Real Time software.

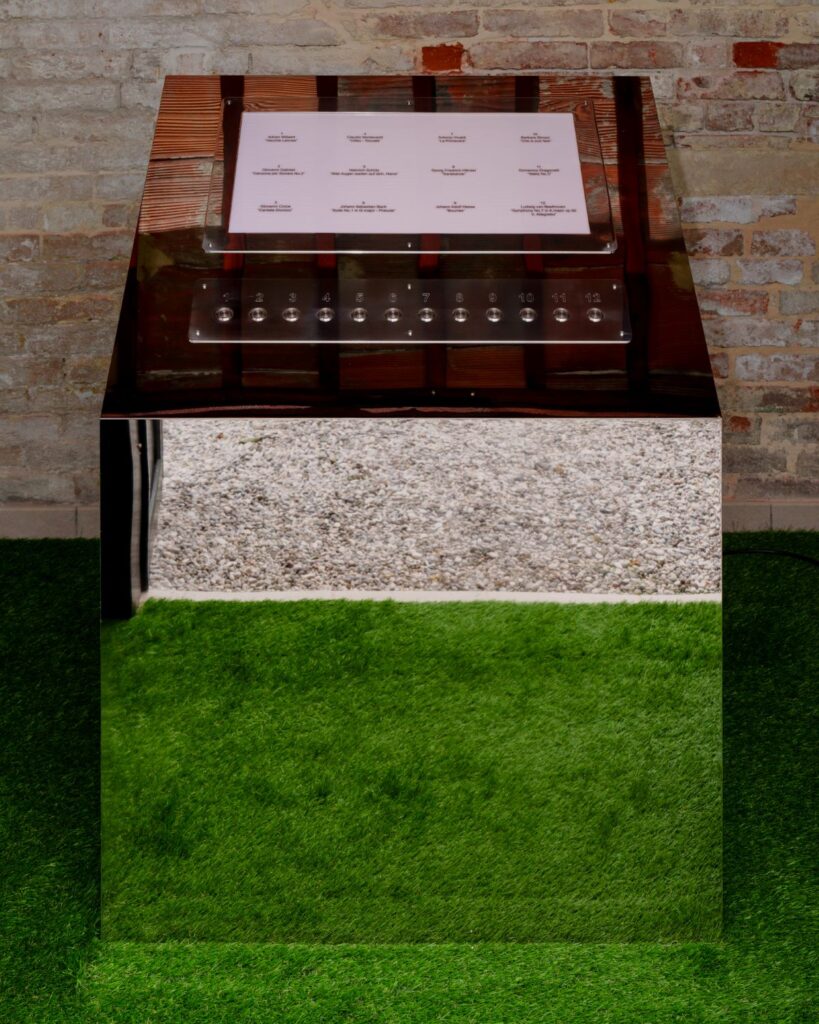

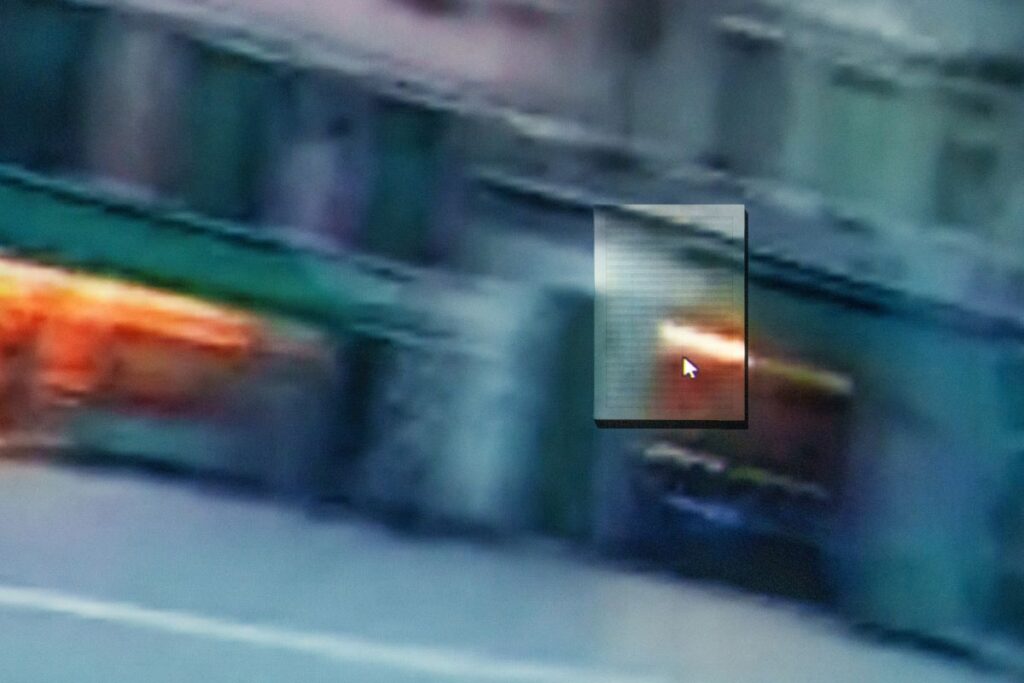

The project was specifically conceived for Capsule Venice and featured two interconnected bodies of work reflecting the artist’s will to explore the nexus of sound and visual art: Joog Box (2024), a custom-made jukebox covered in super-mirror stainless steel displayed in the garden shed, Real Time (Venice, Sept. 21, 2024) (2024), an audio-visual work intertwined with a series of hand-drawn scores on canvas including Real Time / Music Score (Venice, Sept. 21, 2024) (2024) and Music Score (Venice, Sept. 21, 2024 No.1) (2024), all arranged in the annex gallery space.

Though the first “jukeboxes” were known by many names during their introduction in the 1890s – mostly often as “nickel-in-the-slot machines” – the roots of the word “jukebox” go much further back than the first reference found in Time magazine. The term reaches back to the jook houses that emerged during the period. The term originated, however, in the Sea Islands, just off the Carolinas, where Gullah, a creole of several West African languages and English that grew up among slaves, was brought to the region in the eighteenth century. In Gullah, the word “joog/jook” meant “disorderly” or “living wickedly.” A jook house was a sort of dance hall, gaming room, and brothel all rolled into one.

Joog Box was purposely selected, employing the original spelling, as the title for the piece on view. On first hearing, the sounds emitted when a visitor pushes the button of the jukebox is an anarchy of harmonies, an auditory derailment that seems barely related to the scores listed on the screen, and representing the original scores from which the compositions depart. The twelve tracks selected pay homage to the work of composers spanning two hundred years, from the Renaissance to Romanticism. All of the artists once lived and worked in Venice or are somehow related to the city’s history or to one another.

This selection does not aspire to be philologically complete, or offer a strictly historical survey. It is rooted first of all in the artist’s own taste and understanding and it offers scores spanning a wide range of styles and eras, from the founder of the Venetian School, Adrian Willaert (1490-1562), to Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643), from Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) to Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827). What the audience hears comes from a specific process that overturns conventional compositional grammar.

The soundscape – including animal, landscape, and human sounds – was recorded using a microphone, then it was transmitted into the Real Time software. Whenever the software detects and decodes – without manipulating – the sounds or noises in the ambient soundscape most like the notes in the original score, the relevant note is captured by the software and linked to the relevant notes in the chosen piece. In this way, the sounds from the natural soundscape replace the original performance. When no sound is found, there remains a void, causing a feeling of disjunction where the original score interferes with the one performed by the soundscape. What lies at the core of the work is a miraculous incident the function of which plays a leading role in the artist’s poetics.

As the artist affirms:

The incident is, in light of all this, the annulment of the void through a fortuitous occurrence, a ‘collision,’ in our case, between a codified language and the continuous acoustic flow of the landscape. In this sense, it is implicit that categories such as ‘beautiful’ or ‘ugly’ are not applicable; even less so ideas of ‘success’ or ‘failure.’ Coincidence becomes the unique and foundational value to consider, both in its occurrence and in its not happening. The manifestation of an overlap that becomes, in this case, a true fusion between the expectation of a written sign and a natural occurrence, placing us, as never before, within the flow of time, and, for the same reason, beyond it. From listening to the results, produced together with the LIM, I want to express a further consideration as well: returning to nature, the musical execution historically assigned by civilisations to the artificial emulation of it yields a surprising result. It necessarily makes us reflect on the human construction of language and its rules.

Ph. Riccardo Banfi. Courtesy of the Artist and Capsule.

Visually, Joog Box exemplifies a typical trait of the artist’s practice: although its reason for being is sonic in character it has evolved into a mixed-media artwork that includes a strong visual component. It is impossible not to be fascinated and surprised by the striking visual effects of the polished surface encasing the jukebox that reflects the surrounding landscape of the lush garden. The material chosen for the jukebox stresses its alien nature, as if it were a monolith coming from an outer dimension, a time capsule condensing past and future and whose way of communicating doesn’t adhere to any known logic. Joog Box thus expresses the conflictual aspects of the dialogue between human beings and nature; time emerges as the central subject and the critical reason for the artistic dialogue.

The videos projected in the annex gallery space intertwined with a series of hand-drawn scores on canvas unfold another type of visual tension. They visualise the way in which the software works by combining images captured in the Giardini area, which portray human “catalysers” moving in the space as they create a new version of Antonio Vivaldi’s La Primavera (Spring). Here, the audience witnesses a visualisation of the openness of the score, of time, of a never-ending process in which the flow of life and nature – which has no consciousness of numbers or timelines – encounters the rigid logic of humans who rely on numbers to compose. This real time, unconscious composition brings an unexpected aspect to the work going beyond standards of beauty or harmony, because the actual “actors” have no sense of being involved in creating a new piece; they just create it by existing, thus expressing a new mode of authorship.