Of all the Hi-Fi devices I had previously heard, her father’s B&Os were unsurpassed. It made me think even more about her. She, American folk, young Leonard Cohen, Modern Jazz Quartet’s Bach interpretations, red wine and the largely colorless sound of the B&O speakers, the ability of the tonearm and the cartridge to dig new depths and details out of the record groove, created my latent interest in sound quality when I was 14-15. Listening to music on B&O was the most civilized thing I could think of.

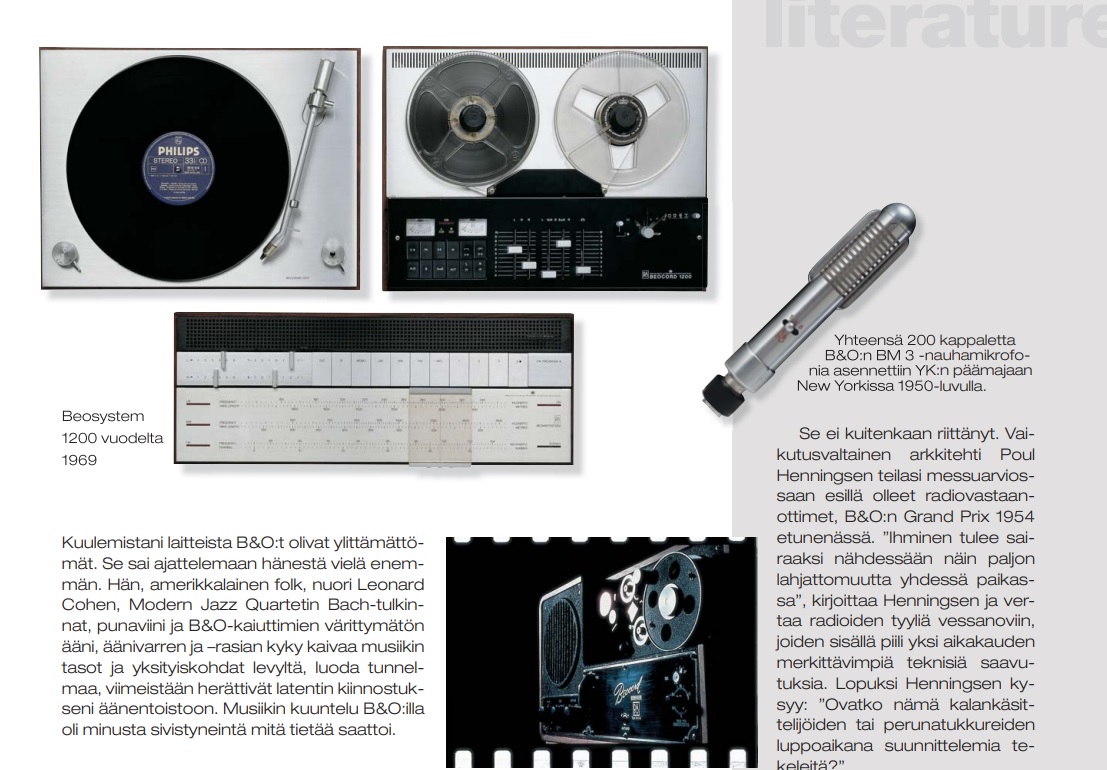

The images below are not from the Book but from an old article about the book.

From crisis to crisis as a winner

It was time when B&O had – once again – made its way out of one of its many crises. The Nazis and their minions had burned the B&O factory down during the last months of the war. Tape recorders and televisions offered new opportunities, but the markets were still uncertain. With its new products lines and especially televisions, B&O was able to maintain its pre-war reputation as a manufacturer of quality Danish products.

But that was not enough. The influential architect Poul Henningsen evaluated radio receivers displayed at a trade fair, the B&O Grand Prix from 1954 among others. “One feels sick looking at so much lack of talent in one place,” Henningsen wrote, comparing the style of the radios to toilet doors, which hold inside one of the most significant technical achievements of the era. Finally, Henningsen asked, has these things be designed fish processors or potato wholesalers in their spare time?

B&O felt indignant but learned a lesson. Cooperation with architects was intensified. In the late 1950s, both traditional-looking and elegant ‘architectural models’ were available on one and the same B&O’s equipment. The design versions did not sell, but B&O gained more experience working with technicians and designers. The below Modular system from 1958 was presented at the trade fair in 1958. The use of colors strongly predicts the 1970s.

And this was not the first time. Already in the 1930s, architect Ole Wanscher criticized B&O’s Art Deco and exoticism driven gramophone/radio receivers. This time, a recently hired salesman of the furniture store was suspected to be the designer. A year later, B&O launched the modern, Bauhaus kind of Hyperbo 5 RG Steel radiogram recorder whose obvious model was Marcel Breurer’s steel-legged Office Chair.

The final change in strategy came with the transition to stereo in the early 1960s. B&O discontinued its two-model business idea, and was now targeting the international market exclusively with “all in one” products that would also appeal by their visual look. In marketing, consumers who care about quality and design rather than price were chosen as the target audience. “For those who discuss taste and quality before the price” was the new slogan. In addition to the products themselves, the company felt that it needed to be able to communicate properly with its customers.

The new strategy led to a series of famous integrated devices such as the Beomaster 900 from 1964. It was B&O’s first mains-operated transistor receiver with speakers on board. However, its most unique feature was flatness, which became a trademark of B&O well into the future. And still is.

The Beomaster 900 with its small but powerful speakers was a success story for B&O, both in Europe and domestically. It helped B&O to cope with the post-war shock and pressure on the Danish radio industry, and to make a move to the European common market. The Beomaster 900 taught B&O that design is not just for experts but a universal language.

The next milestone was the Beolab 5000 from 1967. B&O decided to take part in Europe’s emerging High Fidelity markets with the “world’s best” stereo HiFi system. The Beolab 5000 had a sensitive tuner section, and a 2 x 60 W distortion-free amplifier. What was new, however, was the design. B&O wanted to stand out from the American rack-based look that had a strong reference to professional audio, with its own sleek European style. The transparent slide switches familiar from the counting stick and the aluminum gray front panel were part of the new style.

The next breakthrough, the Beogram 4000 turntable, caused turmoil inside the company but B&O survived and became stronger. Beogram 4000 was one of the most popular record players of its time.

B&O’s decades long investment in design, sometimes ambivalent, was rewarded in the 1970s. The MoMa New York acknowledged the universality of the B&O design language by acquiring seven B&O devices for its permanent collection in 1972.

When B&O was finally convinced that sleek simplicity and adherence to the essentials were its way, and not eg. the technically oriented Japanese style, the future looked brighter. After the Beogram 4000 came the Beomaster 1900 in 1975. Its flat feminine shape, technology hidden under a smooth cover and touch keys immediately took it to many museums around the world, and was part of the 1978 MoMa exhibition dedicated exclusively to B&O products, 39 pieces of them. Only Olivetti, Braun and Thonet had previously received similar treatment. The Beomaster 1900 also became B&O’s best-selling model for the next 20 years.

The Beomaster 1900 was followed by the Beocenter 2200 in 1983; Beocenter 9000 with a CD player in 1986; Beosystem 2500 from 1991; Beolab 8000 active speakers in 1992; BeoSound 9000 in 1996; and so on. And the rest we already remember.

Handsome book

“Bang & Olufsen – From Spark to Icon” is as handsome history book of the company edited by Jens Bang, the son of the founder Peter Bang. The style of the company is reflected in the book too. In the 1960s, B&O hired a graphic designer, Werner Neertoft, to create a new strategic look for the company. Norfort softened B&O’s image and aggressive advertising, adding certain delicacy to it. Following Norfort, B&O’s product catalog, which for long was B&O’s most important means of communication with the general public, received a new graphic look. The products now spoke for themselves without the distracting technical herring salad. In addition, Neertoft introduced elegant ‘blank’ pages that, with their musical and other connotations, counterbalanced prosaic product pages. Jens Bang and his assistants have applied the same look in the book with spacious layout and big clear pictures.

The book tells the company’s journey from its early stages onward. We get to learn how the radio hobby of Peter Bang, the co-founder of the company, led to one of the very first mains-operated radio receiver in the 1920s, partly thanks to Svend Olufsen’s mother’s tax-free income from chicken farming and despite of stern opposition from battery manufacturers.

We learn about the B&O sound system featuring a 25-watt tube amplifier driving three field-coil elements in a big baffle, through which the Danes, for the first time, heard what Mickey Mouse’s voice sounds like. And we learn how Benjamino Gigli, the famous Italian tenor, praised the sound of the B&O’s “Five Lamper” radio receiver from 1929 as beautiful and clear sounding. And how the first Five Lamper with a gramophone was bought by the Danish royal family costing the annual salary of a B&O employee.

Facts like these are nice to know, but the true value of the book is elsewhere, eg. how enjoyable Jens Bang’s book is to browse and view. The text parts are not overly long, and yet informative, and go straight to the point. A less rosy picture of the history of B&O could have been written, but considering the whole, the book is well balanced. “Bang & Olufsen – From Sark to Icon” is a great demonstration of the journey of one of the finest European industrial companies, and a tribute to traditional Danish know-how in sound reproduction and design.

Did you know where the prefix Beo come from? Bakelite. Belgian Leo Hendrik Baekeland gave his name to the plastic he invented. While visiting New York in 1924, Peter Bang realized the enormous potential of bakelite in enabling rounder design of radios and the more versatile use of color. B&O’s first bakelite radio was not completed until 1938, and Bang named it Beolit 39 (pic above). Since then B&O’s products have carried the Beo prefix in their names. Beolit 39 was modeled on Peter Bang’s father’s Buick Y.