Every while and then it is useful for each of us to stop for an inner debate on the ontology of modern abstract art, this time regarding Concrete Art. Concretism is an art movement characterized by the use of non-representational forms, structures and geometry. It was born in Europe in the 1920s and 30s in the mind of such artists as Theo van Doesburg (Netherlands), Max Bill (Switzerland) and later eg. Alberto Magnelli (Italy). And many others. It was van Doesburg who first founded the group Art Concret, with a strong emphasis on geometrical abstraction, and it was him who replaced the term ‘abstract’ with a more positive ‘concrete’.

A joint manifesto from the May 1930 declares that (i) Work of art must be entirely conceived and shaped by the mind before its execution, and shall not receive anything of nature’s or sensuality’s or sentimentality’s formal data (no lyricism, drama, symbolism, and so on); (ii) The painting must be entirely built up with purely plastic elements, namely surfaces and colors (a pictorial element must not have any meaning beyond itself); (iii) The construction of a painting, as well as that of its elements, must be simple and visually controllable. (iv) The painting technique must be mechanic, and exact (ie. anti-impressionistic); (v) An absolute clarity is mandatory. (Wikipedia)

It followed that for the art to be universal, it must abandon all subjectivity and find impersonal inspiration purely in the elements of which it is constructed: line, plane and color. Theoretically the origin of Concrete Art (pure abstraction) has been identified with the synthesis of Russian Constructivism and Dutch Neo-Plasticism in the Bauhaus, in close connection with architecture and engineering (providing new materials: steel, aluminium, glass, synthetic materials etc.).

Experiments in Concretism (06.03.2024 – 02.03.2025) is an exhibition of the EMMA (Espoo Museum of Modern Art) that aims to takes a fresh look at the diversity of concrete art, after 100 years of its invention. More than fifty artists from the 1950s to the present day are represented. The works, selected from the EMMA Collection (plus artworks acquired or commissioned specifically for this show), are said to highlight the formal variety and complexity of concretism and the diversity with which the featured artists use materials, structures and colours. Experiments in Concretism also celebrates the centenary of the birth of Lars-Gunnar “Nubben” Nordström (1924–2014), a pioneer of Finnish concretism, by showcasing the legacy of his work.

COILS

What could be a more appropriate beginning to the journey toward ___ of concrete art than a coil, a piece of electric cable (conductor) wrapped into a coil, just as in Guðmundsson’s (b. 1941) Current Roll (1987). The purpose is to make otherwise invisible electric current inside a cable visible to the eye. “The end of the cable will give you an electric shock!” warns the text below.

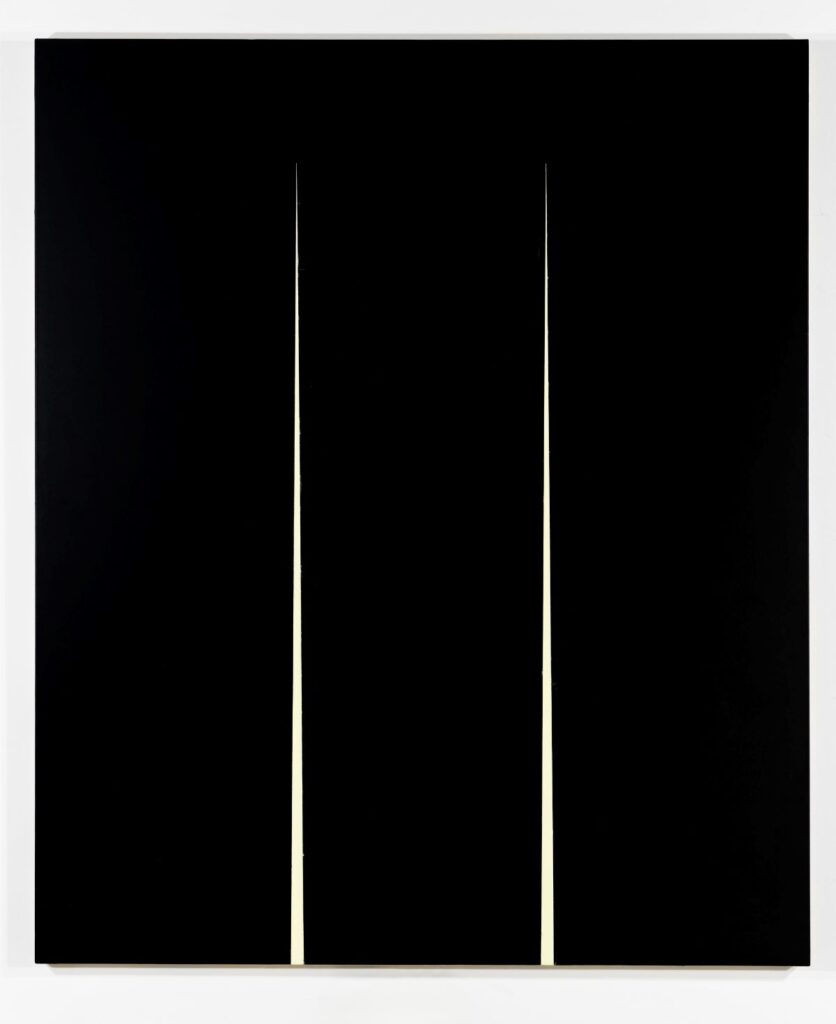

SPIKES

Geometric abstraction can take many forms. Some artists in the tradition are obsessed with the aesthetics of sharpness and spikes. In Ann Edholm’s (b. 1953) Lichtzwang the viewer sees a black surface with two white, narrow, sharp shapes in front of it, but the work also seems to suggest a bright space at the back of the work behind a dark curtain. Edholm says she seeks to attain a sense of the sacred and the physical in her paintings.

SEVERE AND PLAYFUL

Abstract art, and concrete art especially, often appears severe and strict, inhumane. And that’s as it should, but there are more playful examples as well. Maija Närhinen (b. 1967) makes her works mostly with recycled materials, such as used round and rectangular plastic pots that fit inside each other with precision. The colours, shapes and variations in size make the pots not stand still.

BLOCKS AND COLOURS

This work by Silja Rantanen’s (b. 1955), named as Knowledge on the Floor, follows the Doesburg’s manifesto to the letter. Simple plywood blocks (brick-shaped monochromatic objects) in colours taken from a lipstick color chart. That’s it. The colour samples are for Rantanen nothing but colour charts, and she likes them just as they are, without commenting any further on modernism or gender identities.

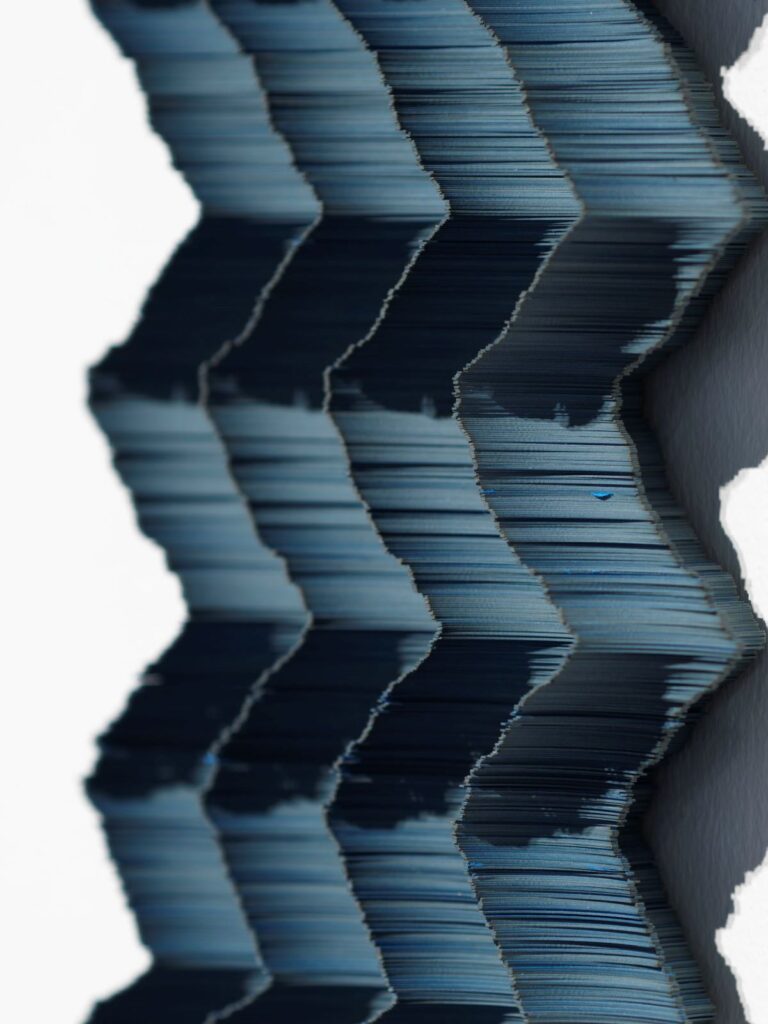

FRAGILE

Many works of Concrete art play with the texture of the materials. Inka Bell (b. 1981) works on coloured using repetition, layering and varying shapes. The works look different from different angles and distances. In line with the requirements of concretism, Bell’s works escape verbal explanation or narrative, but her textures risk of being dangerously sensual.

FROM PAINTINGS TO 3D OBJECTS

Fifties and Sixties onwards, the term Concrete began gradually to be extended to other disciplines than painting, including sculpture and photography. Majority of the works at this exhibition are not paintings. The untitled work of Ragna Róbertsdóttir (b. 1945) consist of precisely stacked blocks of lava and peat. Both materials are shaped by the earth and are the results of sustained processes. This work reminds me of Jopseph Boyes, and the works for which he used felt.

GEOMETRY

Team Play by Elina Autio (b. 1985) consists of twelve identical components, which can be installed in different ways to create new versions. The work is made out of laminated veneer lumber from the construction site, along with triangular strips of wood. This is no exception because apart from colour, Autio’s sculptures and installations often explore materials and structures, and make use of ready-made elements such as pipes and battens. The geometric abstraction of the work reminds the mathematical works of Victor Vasarély.

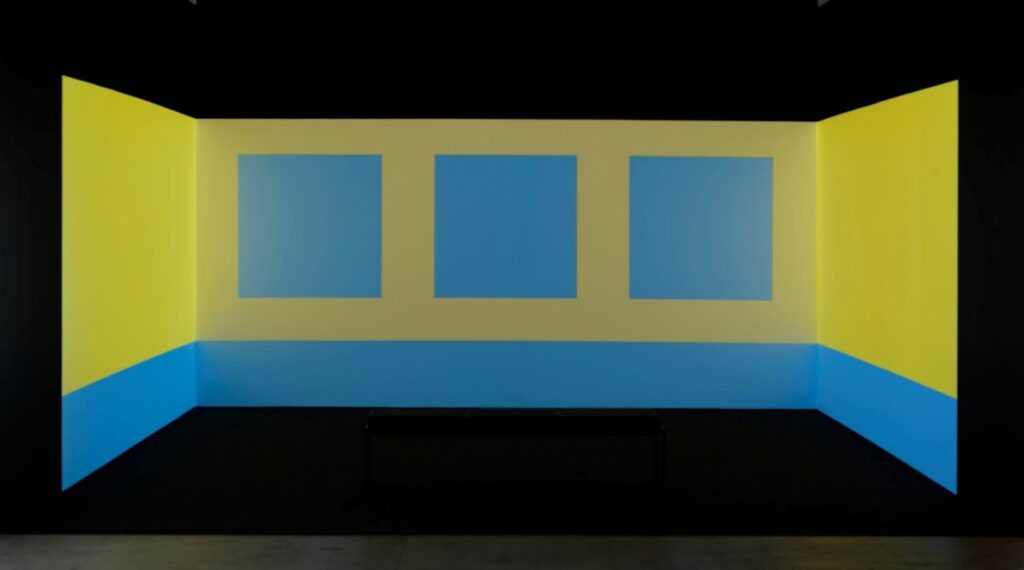

A CONCRETE VIDEO

Pekka Sassi’s (b. 1969) video work COLOURS is non-representational geometric art in that its main operating tools are simple alternating shapes and colours. It’s an immersive 3D work surrounding the viewer, complemented by a calm soundscape. It pushes the traditional boundaries of concrete art towards that of a holistic and spiritual experience.

STEP ON ME

Jacob Dahlgren’s (b. 1970) Heaven Is a Place On Earth (2018) is made on 240 scales (everyday material) that can be stepped on. The work mostly meets the criteria of the Doesburg’s manifesto but the fact that it can be physically experienced is a bit problematic mixing the experience of art with everyday life. Best abstract art always distracts, not attracts. But it is a geometric and symmetric work nevertheless. Food for thought.

WALL TEXTILES ON THE FLOOR

Elina Juopperi’s HERITAGE (2010) is made up of raanus, smooth woven textiles that were traditionally used as a blanket or covering on pole tents in the Northern Scandinavia. This is a much telling example of a modern concrete art: a neat pile of textiles on a concrete floor brought to a large art museum. The whole thing becomes abstract, and the viewer is left with her/his own ideas and aesthetic impressions, activating and challenging the viewer’s faculties of perception. Concrete art and abstract art in general is more about the viewer than on the object of art itself. The more abstract the work is, the more spiritual it becomes. Superiority of concrete abstract art in posing the ontological question is one of its major strengths.

Artists featured in the exhibition:

Timo Aalto, Martti Aiha, Siim-Tanel Annus, Elina Autio, Stig Baumgartner, Inka Bell, Juhana Blomstedt, Bård Breivik, Birger Carlstedt, Kari Cavén, Lars Christensen, Jacob Dahlgren, Sonia Delaunay, Ann Edholm, Carolus Enckell, Beryl Furman, Kristján Guðmundsson, Jorma Hautala, Erkki Hervo, Mikko Jalavisto, Elina Juopperi, Kaisu Koivisto, Ola Kolehmainen, Matti Koskela, Matti Kujasalo, Muriel Kuoppala, Antti Kytömäki, Leonhard Lapin, Maija Lavonen, Ernst Mether-Borgström, Eila Minkkinen, Sarah Morris, Kasper Muttonen, Pekka Nevalainen, Jussi Niva, Lars-Gunnar Nordström, Maija Närhinen, Paul Osipow, Kyösti Pärkinen, Ritva Puotila, Mari Rantanen, Silja Rantanen, Louis Reith, Ragna Róbertsdóttir, Pekka Ryynänen, Piila Saksela, Pekka Sassi, Hannu Siren, Sandra Sirp, Airi Snellman-Hänninen, Antti Ukkonen, Raimo Utriainen and Irma Weckman.