Decadent: a person or a community, characterized by or reflecting a state of moral or cultural decline (decay, degeneration, self-indulgence).

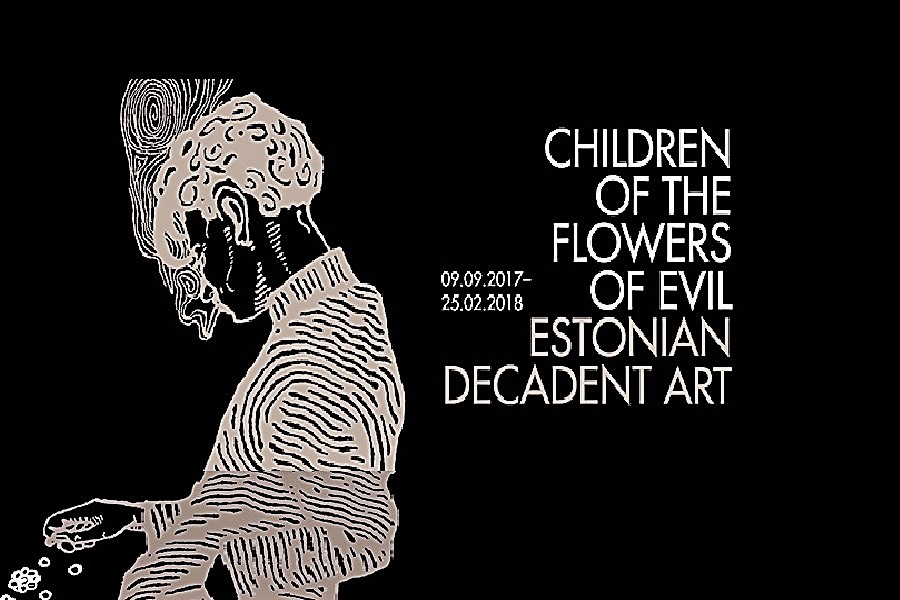

Decadent art? One would expect that it’s art dressing the state of moral or cultural decline in a visual form. Wrong. Decadent art is multiplicatively more than that, and one of the great features of the “Children of Flowers of Evil”, KUMU art museum’s exhibition displaying Estonian decadent art of the early 20th century, is that it doesn’t content itself just to show the public the imagery of the ”decadent art”. That is, it doesn’t just demonstrate how the idea or ideology of decadence simply manifested itself in the paintings of a few Estonian artists that could be classified as being part of the larger decadent artistic movement.

Instead, the exhibition turned out to be a thorough research study providing analysis of the ”decadent spirit and searches of the Estonian artists of early 20th century” by establishing comparative links between literature and fine arts. That is, the exhibition went a way beyond pure aesthetics, and I’m glad that it did.

What sort of study? Analysis?

We are told that ”decadent art (degenarated art) was born out of the growing awareness that the great achievements of modernisation: urbanisation, individual freedom, material wealth, appreciation of success, and a cosmopolitan civilisation founded on rational/scientific knowledge and technology, were not producing the brighter future it had promised earlier in the 19th century”. That is all fine. It places the exhibition in a historical and social context, the late 19th-century Western Europe ”swept by revolt and pessimism, anarchy and hysteria”.

Interestingly, in Estonia (so it is said) “reactions to abruptly accelerated social modernisation and celebrated individualism coincided with a rise in national self-awareness. Trying to rid themselves from the influences of the superimposed Russian educational system and German cultural influences, and to create indigenous culture, a group of Estonian artists revolted against bourgeois and outdated academic approaches to art (eg. national romanticism) by introducing a more ambivalent perception of modernity in order to consciously modernise and Westernise Estonian culture.”

Dwelling on European or Estonian roots of decadent art could make one ponder whether the exhibition, and its background research project, would just offer an overview of the history of art and cultural policy. Wrong again. To the spectator’s positive surprise, the exhibition exceeded historical and cultural concerns, and chose a more profound and intimate approach: that of social-psychology and literary criticims.

Beaudelaire

Beaudelaire

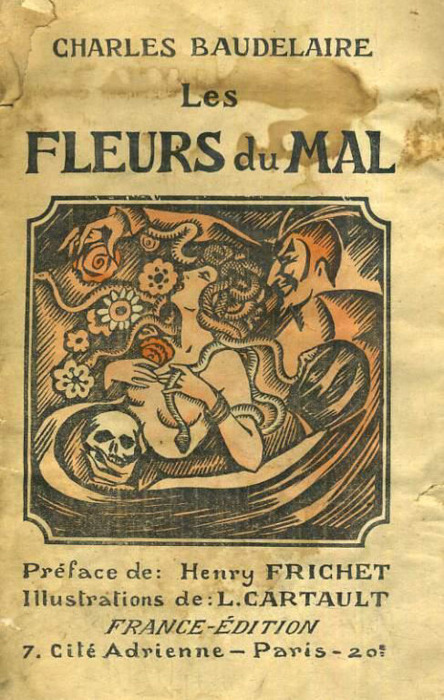

As the title of the exhibition suggests, the exhibition was wrapped around Charles Baudelaire, the father of symbolism and decadence, whose writings are a precondition of understanding modernism. The exhibition was divided into nine sections or departments, all labelled after Baudelaire’s poems from The Flowers of Evil (Les Fleurs du mal, 1857) and the book Artificial Paradises from 1860.

The paintings displayed were not directly linked to Baudelaire’s texts, but rather aiming to exemplify ”semi-conscious and unconscious divergences and elaborations in modernising, hence decadent, Estonian art”, its most significant topics, images and moods of decadence.

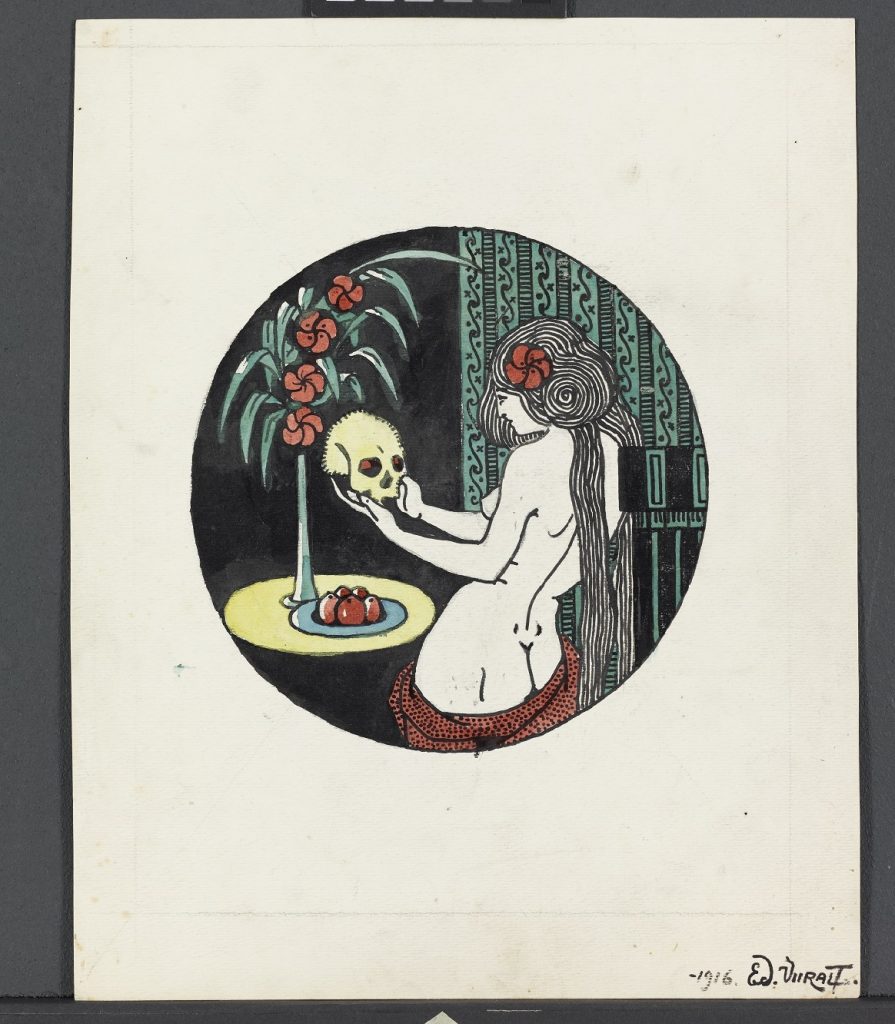

The “Flowers of Evil” was the first attempt to gather together Estonian decadent art of the early 20th century: many of the works by Eduard Wiiralt, Ado Vabbe, Erich Kügelgen, ALeksander Promet, Erna Brinckmann, Erik Obermann and others – the children of flowers of evil – have never been displayed before.

Aesthetics of ugliness

Baudelaire’s Flowers of evil didn’t become the title of the exhibition by accident. The name bears an important symbolic function, as is pertinent to an exhibition dealing with decadent art. It was Baudelaire who taught the Western world to see, in flowers, more than just beauty and an ”unattainable ideal”: (idealization of) melancholy, sadness, desease, mystery and decay (toxic). Thus Flowers of evil can be taken as a lesson of ”aethetics of ugliness”: the artistic beauty hidden in ”ugly” such as ”decomposing carcass, syhpilitic prostitute, wounded soul, wild night life”, and to see beauty, pleasantness and enjoyment in such works. Beaudelaire was a ”game changer” (pardon me the modern expression): without him this exhibition, along with any other exhibitions of modern art and literature, would not have been possible.

Since decadent artists were fond of ”unusual beauty” (subtle and peculiar beauty intertwined with melancholia and mysticisms) it was only natural that their search, by definition, contradicted bourgeois norms and values, sexual and other.

Soul wanders in the gutter

If it is hard to see ugliness and decay in flowers (it isn’t in fact), it was certainly not hard to see it in the way Estonian decadent artists depicted themselves (self-portraits) and their fellow artists: spleen, sullenness, melancholia. Or in images on brothels and cafes ”where blase souls search for solace”. These works also include depictions of mental and perceptive disorders (as seen in “distorted physiques, illustrations of hallunications, hysterical-grotesque characters and so on”). This section of the exhibition made me a strong impact.

Dance macabre

Another intriguing section of the exhibition was the one devoted ‘dance macabre’: “esthetically celebrated, sensually fantasized morbidity, love for the skull, angels, death”. The supporting pessimistic cultural theories and philosophies are said to have came from the pen of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Freud. One might think that the horror movies of the late 20th century would continue the tradition, but their ‘philosophies’ come from the Hollywood entertainment houses. Decadence exported to the extreme?

The litanies of satan

Many examples are shown of the fact that “erocitism dominating decadent art does not show good taste and often exhibits imaginative-perverse scenes”. The purpose of these works is to sit on a fence between being dangerous and attractive at the same time. An important sub-culture is formed around ”fatal erocitism”: “satanic or blasphemous imagery starring a satanic male figure, symbolizing human being’s slavery to natural-bestial instincts”.

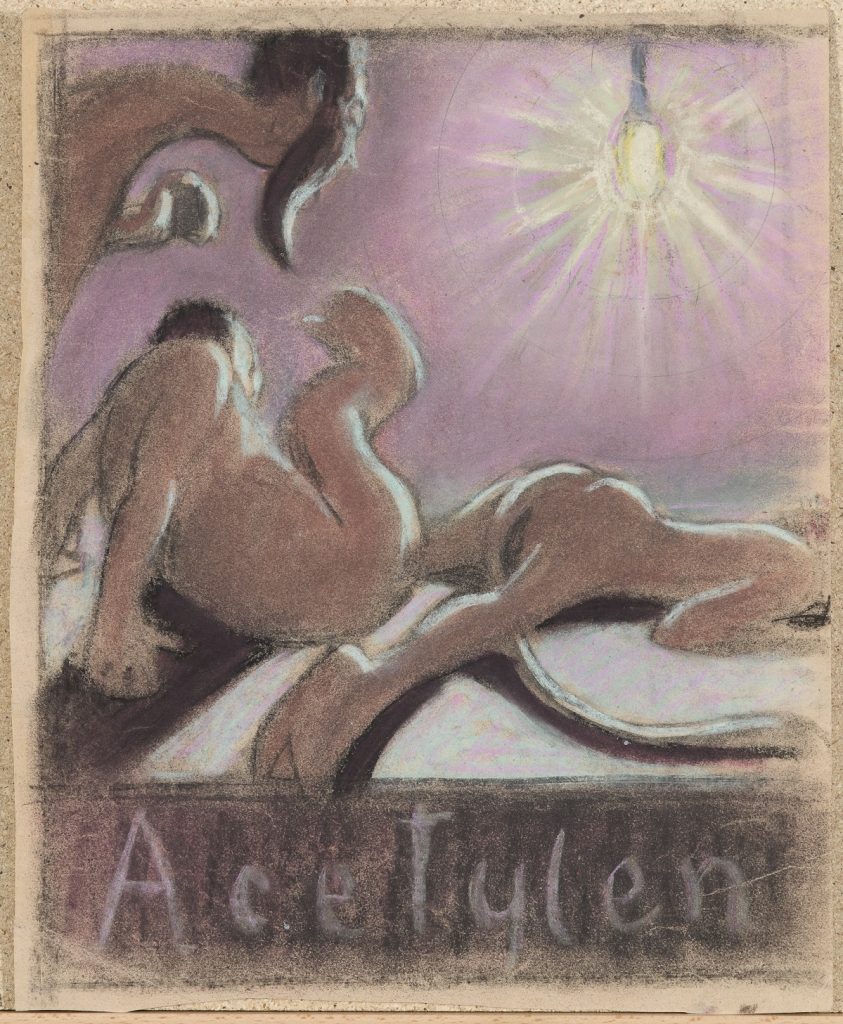

Arificial paradises

If, on the one hand, decadent artists glorified decay and degeneration, they also seeked ways of escaping it, ”ways of getting rid of sullenness or of retreating from the real world”. These artificial paradises could be theatres, cafes, cabarets or brothels (bordells), as could be seen in works of this section, some of them hilarious to look at!

In majority of the works women are often depicted in vulgar ways, eg. as prostitutes, as vampires, in the wilderness, with animals, as a sphinx, as an enchanting dancer. The ambivalence of decadent art shows up here too: a modern, sexually active woman was seen as dangerous, sickly and weak but also admired as a latent ”artificial paradise”.

Technological pessimism

The discourse of decay and decadense in the late 19th and early 20th century Europe focused, to a great extent, on the decline of Western civilisation, and typically took a rather critical attitude towards it. This was expressed in the works of many artists and literary circles of the time, and the exhibition as well.

Against this, the Flowers of evil (the accompanying text) stresses the importance of ambivalence with which artists and writers approached the modernity and modernisation, and its achievements. It is pointed out that “alongside the negative, decay and decadence also meant the possibility of positive deviation from traditional norms and values and approaches to subject matter and art”. Moreover, some would associate the decadent art with certain optimistic attitudes, as it appears to go well with dominance of the subjective viewpoint and extremely individualistic, liberal society.

Anyway, having gone through the exhibition, and having exposed myself to all of its artworks, I was confident that pessimism and the critical view was the dominant and correct one. First off, the praise of individualism and personality itself goes hand in hand with narcissims, nihilism, cynicism, melancholia etc. Not much of help from that direction. But more importantly, as emphasized in the beginning, despite the great achievements of modernisation: urbanisation, individual freedom, material wealth etc., the future didn’t look especially promising to those of us who were most sensitive: artists and writers. All the rational/scientific knowledge and technology available, with all the wealth and health it promised, it wasn’t able (beyond a certain minimum level of sustainability) produce ways of living (existence) that would enable them to be in a meaningful and rich relationship to their work, or to find ultimate satisfaction in their human relationships. These are structural consequences caused by the modernisation process. It’s the cost people in the Western world have to pay for their modern life style and living standard. It’s highly interesting and impressive even that, as the exhibition proved, the first symptoms of the misfortune and uncomfortableness of being were seen already in the late 19th and early 20th century.

Here’s what Jaan Undusk (Director of the Under and Tuglas Literature Centre of the Estonian Academy of Sciences) writes in his foreword to the Flowers of evil -exhibition, and in which I find a seed of wisdom:

”Decadent culture, with the extremely asocial poignancy of its imagery, was a manifesto of creative non-adaptiveness. Audiences had hardly ever been faced with such enormous amounts of pathos faced, which irritated the collective health of society. The urge for total spirituality (melancholy, Platonism, symbols, alcohol, narcotics, hallunications and metaphysics of death), as well as total physicality (sexuality, illness, over- and under-developed bodies and body parts, corpses, anmals, plants, ecstatic and distressing smells, riots of colour born in the slanting rays of the setting sun and other landscapes of the senses), was probably intended to compensate for what machine-based progress had threatened the most.”