Fragrance of the orange / Flowering at last in June / Wafts through the summer night / The memory of scented sleeves / Of someone long ago

The sense of taste, touch and smell are senses of a primitive man. They penetrate human rationality more efficiently than hearing, not to mention the vision. How the related sensations are experiences is often in a completely different way inexplicable as listening to music or viewing an image.

Of all the sensations, the sense of smell is the most fleeting and subtle. The importance and impact of odors and scents was known and appreciated in Ancient Greece, in the Roman Empire, in Egypt and elsewhere in the Middle East even before the Christian era. Of the subsequent cultures the most advanced, France, China and Japan, have refined the art of odors.

Although it may be hard to believe in our odor-free times, unpleasant odors are fundamental to human life. Masking the natural odors with new, pleasant ones, as well as pleasantness of fragrances itself, lead to the development of the art of perfumes in Europe, mainly in France. In Asia, first in China and then in Japan, the odors/scents were first more closely linked to religious practices and beliefs, which led to burning incense. While perfumes are still extravagant fun of residents of the West, incense has become part of popular culture in Asia.

Although it may be hard to believe in our odor-free times, unpleasant odors are fundamental to human life. Masking the natural odors with new, pleasant ones, as well as pleasantness of fragrances itself, lead to the development of the art of perfumes in Europe, mainly in France. In Asia, first in China and then in Japan, the odors/scents were first more closely linked to religious practices and beliefs, which led to burning incense. While perfumes are still extravagant fun of residents of the West, incense has become part of popular culture in Asia.

The Latin word perfumum, from which the word “perfume” is derived, means the ”smoke” coming from trees and plants. While playing with perfumes people do not always remember that the scents are originally connected to burning of an aromatic substance obtained from the trees and plants (less often from animals). The smell of incense too is almost always based on a combustion process. Unlike perfumes, incenses are always natural substances, never synthetic.

Burning incense spread along with Buddhism from China to Japan in the 6th century. At first, a mixture of 5-7 aromatic substance was used in rituals; eg. aloe tree (jinkoh), sandalwood, clove, cinnamon and camphor. The mixture was thrown in the embers.

Jinkoh ie. aloe tree had a special position from the outset in the tradition of Japanese incense. Jinkoh means heavy, “water submersible” wood, which emits a strong aromatic smell when burned. No one knows exactly on what the tree’s aromaticity is based on, other than that it is some rare biochemical reaction.

Two early pieces of aromatic jinkoh are stored in a temple built in the Eight century. The larger piece, which was a gift of the emperor to the temple in 756, originally weighed 13 kg. Today, 1250 years later, its weight is 11.6 kg. Small pieces of the wood have been used for a variety of festive purposes over the centuries. In contrast to perfumes, which when oxidized, lose their flavor in 25 years, frankincense ?? fragrance remains the same for hundreds of years.

Towards the end of the first millennium, the tradition of incense in Japan disengaged from religious rites. From this so called ”useless use”, soradak, emerged for example the tradition using smells for rooms and clothes, smell-related games and poetry and the art of fragrances in general, in addition to the art of tee ceremony and flower arrangement. From this period also is transmitted the praise of seasons with scents, occurring only in Japan.

In Kamakura period (1185 -1333) people moved from burning mixes of smells to burning of frankincense. The “incense road” peaked the Muromachi period (1336-1573). From that time on the ceremony of “fragrance listening” is known, in which the participants of the ceremony, under the supervision of the ceremony master, detect scents by listening to them (mon-koh).

The ceremony resembles blind tests of the audiophiles. In one version of Mon-Koh the master of the ceremony selects three different types of incense (eg. mist in the capital, september wind and Shirakawa border station). After having done that, he burns two of them as samples (say, mist in the capital and September wind) telling participants which scents are in question. He then mixes the order of the incense and burns each of them for a certain period of time participants not knowing what is what. The participants listen to each scent in turn and mark their answer on a sheet of paper. Responses are then evaluated.

The ceremony resembles blind tests of the audiophiles. In one version of Mon-Koh the master of the ceremony selects three different types of incense (eg. mist in the capital, september wind and Shirakawa border station). After having done that, he burns two of them as samples (say, mist in the capital and September wind) telling participants which scents are in question. He then mixes the order of the incense and burns each of them for a certain period of time participants not knowing what is what. The participants listen to each scent in turn and mark their answer on a sheet of paper. Responses are then evaluated.

But why must the scents be identified by listening, and not by smelling? The explanation can be found in Buddhism. In an old writing called Monja, (the Buddha’s wisdom and intelligence belong to the patron) a Saint tells how, in the world of Buddha, everything has its own scent, including Buddha’s words and teachings. So burning of incense is like listening to the words of Buddha, rather than smelling. (Burning of myrrh in the Bible results in a scent that was believed to be able to convey messages between the dead and the living.) The underlying idea behind listening is also that unlike many perfumes, smells of incense are truly fine-grained and weak, and therefore recognizable only by listening!

Listening to fragrances, in all of its dimensions, was most popular in the 18th century Japan. It was regarded as the highest art form, and placed on top of tea ceremony, poetry and music performing. Mon-koh books became more common, and the practice of the ceremony was taught in special incense schools. When Japan started to open up to the Western world in the second half of the 19th century, traditional Japanese arts began to lose popularity – listening to scents included. Also, search for the mass popularity had transformed listening to scents more commercial, emphasizing technical skills and superficial ritualistic features instead of pure aesthetic appreciation.

However, Mon-Koh tradition revived again in the second half of the 20th century. The old incense schools, Oiye and Shino, who are still in operation, began to teach again the old tradition of listening to fragrances.

Shoyeido is one of Japan’s oldest incense shops. It was founded about 1705 in Kyoto, where it still continues to influence. Shoyeido has made Mon-Koh known in the Western world from the end of the 19th century onwards. In recent decades, it has also developed many new fragrances and other incense products such as cone and coil shaped incense.

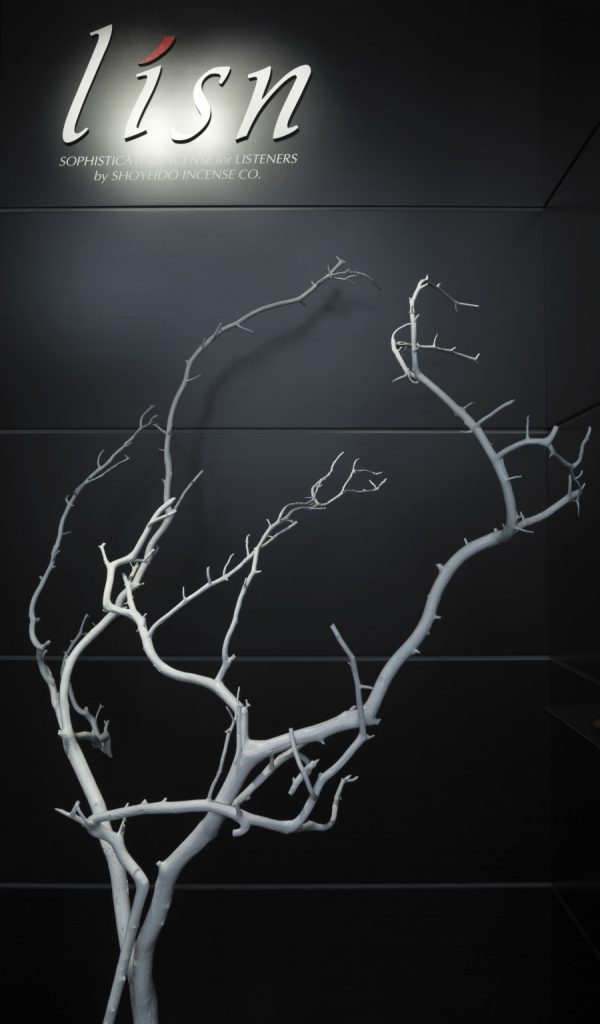

Lisn – Sopihisticated Incense for Listeners – is Shoyeido’s side branch. Lisn products combine traditional Japanese aesthetics with modern. Apart from Kyoto and Tokyo only one Lisn shop exists in the world, and that is situated in Helsinki.

The shop sells about 120 different kinds of fragrance – classics as well more modern ones – out of the total 260. The shop is tastefully decorated taking into account the spirit of the products sold.

Each incense has its own name and comes with a definition of the picture (eg. “The quiet bouquet of Same of Rita”, “The cactus clarity of Naughty”, “Squall with white flowers in Rhythm”), which the fragrance is meant to evoke. The description is meant to stimulate the imagination of the listener.

The sticks are carefully selected and hand-packed in design boxes. The boxes and other paraphernalia have been designed by internationally known designers such as Harri Koskinen and Ilkka Suppanen.