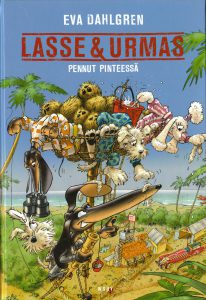

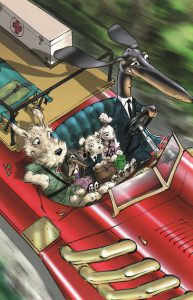

In Eva Dahlgren’s four children books (2001-2007) the dogs – the dachshund Lasse (an ambulance driver) and a poodle Urmas (a male nurse) – are the stars. They dream in their dreaming potholes until they get an idea. Very often the idea is about going to some place. One way or another Eva’s children books are about leaving for somewhere.

Preparations are made in their home territory, Hurtholm. The dogs take swimming lessons and language lessons. They build a rocket, collect useful gadgets for the travel. Tough situations and numerous obstacles they overcome with their wit.

Dahlgren’s children books are adventure stories, and that’s how Dahlgren wanted them to come out. Her favourite books from her childhood are Francine Pascal’s ”Sweet Valley High” and Enid Blyton’s ”Famous Five”. The influence of the latter is fairly obvious.

There is action, there are quick turns in the plot. Some events are, perhaps, too obvious and the text too explanatory for adults, but children read it differently. And children’s judgement Eva trusts, although she doesn’t write for them only.

The stories are products of her imagination, but they are not asburd or unreal. Dahlgren’s children books do not represent the nowadays so fashionable fantasy literature. The books don’t describe another reality; for Eva the perceived reality is a much greater source of inspiration than the imaginary world seen from inside.

Adventurous as her books are, emotions are always present. The dogs are sad, and the dogs are joyful. ”Never stop dreaming” is their greatest consolation. Eva has said that more than anything she wants to convey feelings of togetherness and reunion. These feelings have a deeper personal ground but at the same time there is something genuinly Swedish in them: the dogs sincerely care about their fellow dogs, also globally.

As is common in the tradition, Eva’s books too are tiny morality stories. The ideal society is such where sensible and sensitive dogs – people – are tolerant towards each other. While reading Eva’s children books one starts to wonder how, if at all, is their text related to her other literary outputs, lyrics for example?

As is common in the tradition, Eva’s books too are tiny morality stories. The ideal society is such where sensible and sensitive dogs – people – are tolerant towards each other. While reading Eva’s children books one starts to wonder how, if at all, is their text related to her other literary outputs, lyrics for example?

Inner: Having read the three Lars & Urban books it seems to me that writing music and writing books for children are two separate aspirations to you: the former being far more personal than the latter. Is there any truth in this, and is there anything at all in these stories that is fueled by e.g. your childhood memories?

Eva: They are almost two completely different things. Writing music is like a moment of meditation, to get in touch with one’s innermost, to illuminate each corner of it and then try to find words for what I see. To write a book for children is like trying to tell a story in the most entertaining way possible, while trying to get the reader understand the message written between the lines. In my children’s books there is of course much of myself. In all of the books there is one character that bears more on my personal characteristics than the others, and much of my life now and memories from my childhood, are the basis for the stories I tell.

Inner: Lars and Urban are frequently dreaming, and often their dreams relate to leaving for somewhere. What does this tell of them? Is it simply for narrative reasons that Lars and Urban are not fully satisfied with their present life as it is? Dreaming, longing for something, is also to be found in your lyrics?

Eva: To long for something is to maintain curiosity towards life. Longing is one of the strongest instincts of self-preservation, a survival instinct. Not longing is to give up. That does not mean that one would not enjoy his or her life as it is. Longing and dreaming is something very private, and that is why it is so wonderful to the friends, Lars and Urban, that they can dream together. It shows that they are emotionally mature. Two emotionally courageous dogs, ha ha ..

Eva: To long for something is to maintain curiosity towards life. Longing is one of the strongest instincts of self-preservation, a survival instinct. Not longing is to give up. That does not mean that one would not enjoy his or her life as it is. Longing and dreaming is something very private, and that is why it is so wonderful to the friends, Lars and Urban, that they can dream together. It shows that they are emotionally mature. Two emotionally courageous dogs, ha ha ..

Inner: Your children books appear to be classic adventure books with action and incidents. But they’re also emotionally loaded. In another interview you picked up the feelings of togetherness and reunion as the emotions you wanted specifically to convey. Why these two? For the sake of promoting sociability? For some more private reason?

Eva: I grew up at the library. It was our kinder-garden when I was little and when I was a teenager. I read everything. High and low. From comic books to Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago to manuals on how to build a composting toilet. What separated good from bad was reunion. Without that I really needed to think about it, I grew and matured as a person just because I could identify with the characters in the books, people or animals, who were at a crossroad in their life or faced a moral dilemma.

I want to live in a society of emotionally intelligent people. Children understand more than adults believe they do. My books are my small contribution, but nevertheless. That’s my private reason.

Inner: Lars is after material wealth (gold), Urban seeks personal love. Is your message here that there’s an ongoing tension between the two sources of personal security?

Inner: Lars is after material wealth (gold), Urban seeks personal love. Is your message here that there’s an ongoing tension between the two sources of personal security?

Eva: No, what I want show with these two extremes is that even if we have two completely different goals of life, people can be best friends and best companions. They can have the same love for dreaming, for imagining, build things together, make good sausage stew with chocolate sauce. If there is a common will to play, the Pope and an atheist can be best friends.

Inner: It is generally acknowledged that when writing for children – or composing for that matter – it is important to address adults as well. But can this happen simply by assuming or hoping that children’s preferences coincide with those of the adults, or the other way around? What’s your opinion of this subject?

Eva: Perhaps because of my upbringing in the library and the memory of how I understood the books that were considered too difficult for my age, I write with no regard to age itself. Maybe a few times I choose not to use certain words but I know that one need not have to sidestep all the difficult words, as long as they appear in a context of the story. I can even think that I have a responsibility to occasionally sneak in such words as décolletee, sympathy and dynamics. But when it comes to the story as a whole, it is my strong belief that children and adults are affected by the same content. Good wins evil, love wins hate, forgiveness wins judgment, and impossibility that threats everything becomes possible.

Inner: Your stories are wild and imaginative but not really absurd or unreal. Was it ever on your agenda to write a book on a fantasy world looked from inside? Lars and Urban in the Wonderland?

Eva: I’m not a big friend of fantasy literature. Such stories have never really captured my interest. To me the strange wondrous reality outside is enough. Look out the window! One cannot help but smile.

Inner: You made Lars and Urban be dogs. How well you know dogs? Did you live together with them as a child? Do you own a dog now or have you owned one? If so, which breed, and why that breed?

Eva: I grew up with a cat, Hampus, who lived almost 20 years. I did not have a closer relationship with dogs when I began writing my books but over the years I have developed a great love for them.

Inner: What feature you value most in dogs? Speechless communication? Unlike Lars and Urban, their being always or almost always in a good and happy mood? Their dependence on their master? A good excuse to go outdoors, and perhaps meet same-minded people?

Eva: I like them just for what they are, dogs. They’re different kind of beings. All animals are amazing. Birds. Giraffes. Ants. I am not trying to humanize the dogs I meet, it would be to disparage them. They’re magnificent just as they are. Dogs.

Inner: But you are humanizing Lars and Urban, Urban especially?

Eva: Lars and Urban are not really dogs but not humans either. They are fantasy figures. I think children understand that.

Inner: Have you got something against Afgan hounds?

Eva: Had I been politically correct, I had chosen another breed to play the character. Maybe my allergy shot here, a lot of fur, a lot of colds.

Inner: H.C. Andersen from Denmark, Astrid Lindgren from Sweden, Tove Jansson from Finland … Why do you think Scandinavia has produced so many outstanding authors of children books?

Eva: The darkness, seasons, long distances, tradition of telling stories, relative prosperity … plus we are people with a good taste.

Inner: As a Swede, what’s your mental relationship with Pippi? Or Moomin?

Eva: I grew up with Pippi and Emil, those stories are part of my childhood. Moomin has come to me as an adult.

Inner: How do you find the supply and quality of children culture, not just literature, in Sweden nowadays? Has the very alive Swedish pop-culture cut down the audience and resources from the more ‘serious’ children culture e.g. theatre and opera?

Eva: Right now we have an uneven battle against the internet crap, but I think and believe that quality will triumph over all short-term superficial commercial stuff that prevent children from developing their own imagination.

Inner: Have you ever considered writing music for children?

Eva: I’ll do it already!

Thank you Eva so much!