While attending to the HIGHEND 2024 in Munich this spring, I took a day off just to visit Haus der Kunst München, and witness Rebecca Horn’s retrospective exhibition (26.4.–13.10.24) designed to provide an overview of this internationally renowned artist’s life’s work spanning six decades. I did so believing it would be at least as relevant as experiencing new amplifiers, players and loudspeakers at the Hi-Fi Show. Why is that?

The first placard tells the following:

“The life’s work of Rebecca Horn, … , is concerned with the boundaries between nature and culture, technology and biological capital. Whether described as an inventor, film director, author, composer, … Horn describes her practice as the creation of precisely calculated relationships between space, light, physicality, sound, and rhythm. Her performative, sculptural, and filmic works explore the connections between humans, machines, animals, and the earth. They aim at the physical experience of a visible, tangible, and audible existence.” (my ital.)

Meeting technology at a Hi-Fi Show may, every now and then, be intellectually challenging, it may be childlike inspiring, it may be romantic, it may be nostalgic, and dozens of other genuine (mainly male) emotions and other states of mind. But there is a more profound level in how technology surrounds us, and it’s artists such as Rebecca Horn who are able to delve deeper and bring out these undercurrents, give them an aesthetic look and meaning.

“She does it by celebrating the horror of the machine as a continuation of the body, … creating existences of the unpresentable, and gives a face to the abysmal. Her oeuvre is a lifelong and currently volatile echo of the progressive decentering of humanity.”

Rebecca Horn

Born in Michelstadt, Germany, Rebecca Horn (24 March 1944 – 6 September 2024) initially studied at the Hochschule für bildende Künste in Hamburg in the 1960s, before gaining a scholarship at St Martin’s School of Art in London. In the 1970s and 1980s, she lived and worked in New York and Berlin. She taught as a guest lecturer at the California Art Institute (1974) and the University of San Diego (1974) and was a professor of multimedia at the Berlin University of the Arts for many years (1989–2010). In 2007, she founded the “Moontower Foundation” in Bad König, Odenwald, which is primarily concerned with the preservation, research and documentation of her work. Her works of art, ranging from her first works on paper in the 1960s to the early performances and films of the 1970s, the mechanical sculptures of the 1980s, and the expansive installations of the 1990s up to the present day. These works have been on display in numerous exhibitions over the decades all over the world, a far too many to be listed here.

The below is mainly taken from the written material provided by the museum for the exhibition.

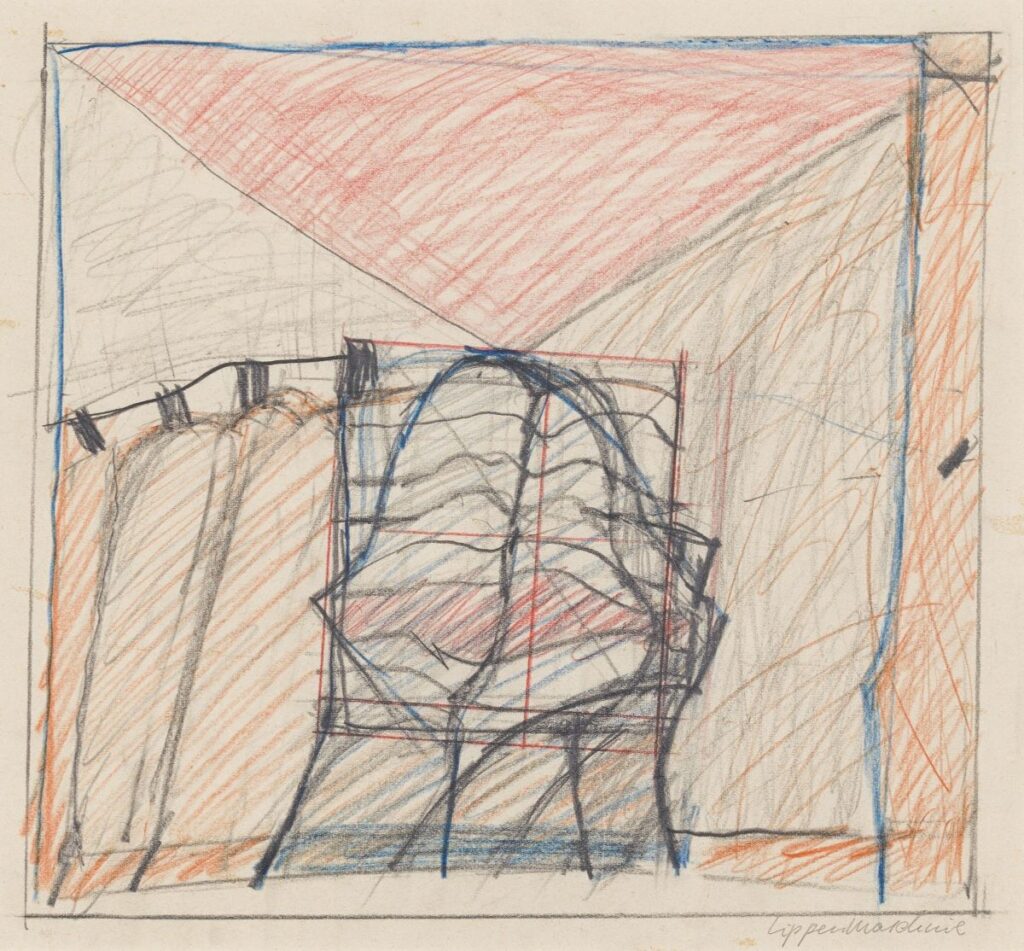

Lip Machine, 1964

In her early work, Horn saw herself first and foremost as a choreographer, centering on the human body and its relationship to nature, culture, technology, but she also created visionary symbols for the interconnectedness of bodies and technology, as shown in her first works on paper in the 1960s. In Lip Machine from 1964, the connections between the human body and technology come out as the fragmentation of bodies, their dissection into individual parts. The title of the drawing creates an image of the mechanisation of a body part read as feminine.

Measure Box, 1970

Even in her earliest sculptures, such as the Measure Box from 1970, Rebecca Horn questions the dissolving boundaries between human and machine. She addresses the protection and vulnerability of the human body in radical ways, focusing on the relationship of bodies to internal and external spaces.

The Peacock Machine, 1982

Horn’s performative early work includes motorized sculptures, such as the Peacock Machine from 1982 with its multiple, long, tapered aluminum rods imitating the impressive raising of the tail feathers of male peacocks during courtship. The sculpture’s endlessly repeating motion sequence is reminiscent of the dissection of movement patterns familiar from industrial production processes, whereas the mechanical movement gives the impression of a living being. The title explains the symbiosis of bird and technology. Here Horn stages the human fear of no longer being able to control one’s own body, referring to automatons and monsters in literature (e.g. Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, 1915).

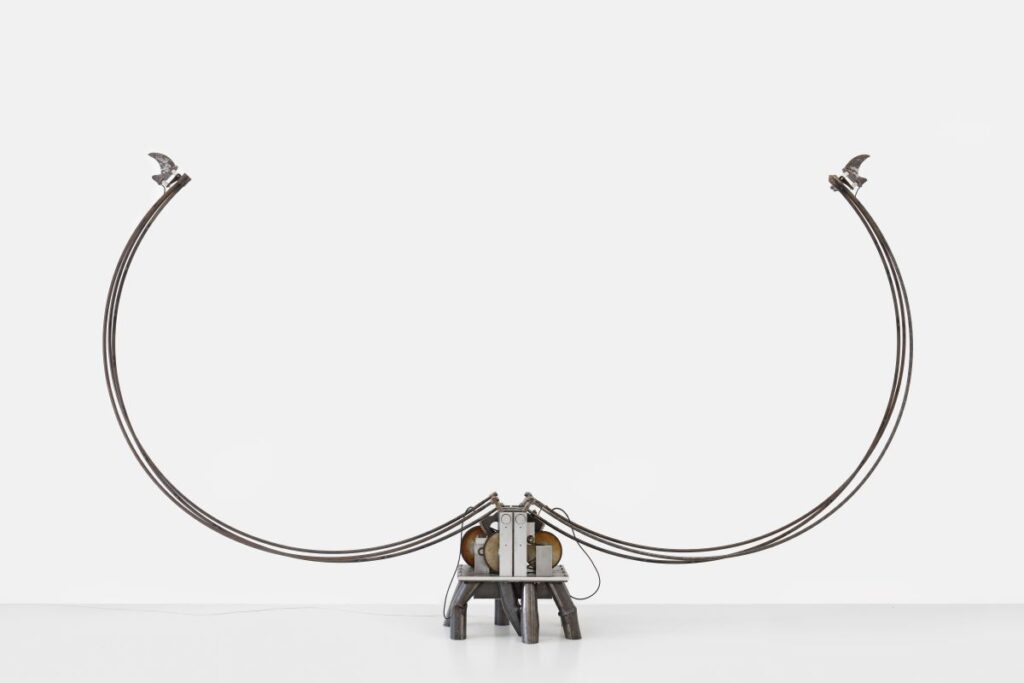

Kiss of the Rhinoceros, 1989

The 1980s onwards Horn’s mechanical sculptures have keep serving as symbols of the interconnectedness of technology and the body, which from today’s perspective seem like bold premonitions of a world controlled by machines. In Kiss of the Rhinoceros from 1989 two semicircular metal rods driven by a motor come together to form a closed circle. When the ends of the fragments, reminiscent of rhinoceros horns, make fleeting contact with each other, an electrical discharge occurs that has the effect of an electrifying kiss. Here sexual energy is visualized in an utmost stripped-down technical manner. By presenting interpersonal encounters through animal-like, animated machines, the artist points to the similarities in behavior and affect between human and nonhuman actors.

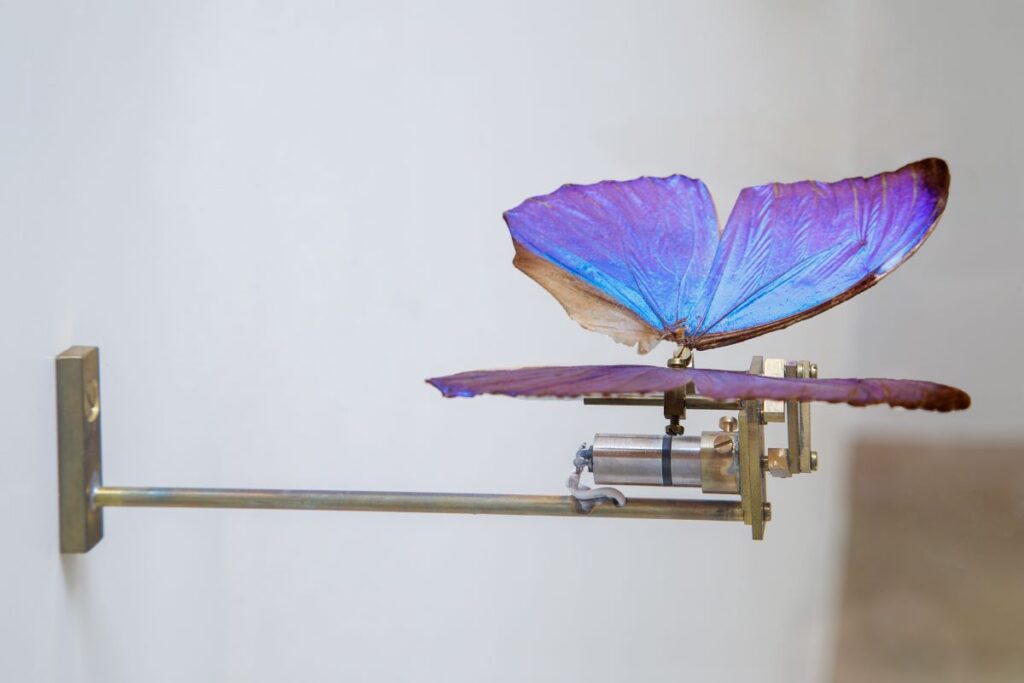

Butterfly, 1990

Here a Butterfly (1990), with a help of a sensor and a electric motor, starts to flap its wings as soon as it’s approached.

Concert for Anarchy, 1990

An upside-down grand piano, hanging from the ceiling by heavy wires, occasionally coming to life in a noisy outburst, spitting out its keys at regular intervals, and composing its own music. This is one example of how Horn’s machines often appear to act like living creatures: “They react as we react. My machines are not washing machines or cars. They have a human quality and they must change. They get nervous and must stop sometimes. If a machine stops, it doesn’t mean it’s broken. It’s just tired. The tragic or melancholic aspect of machines is very important to me. I don’t want them to run forever. It’s part of their life that they stop and faint.”

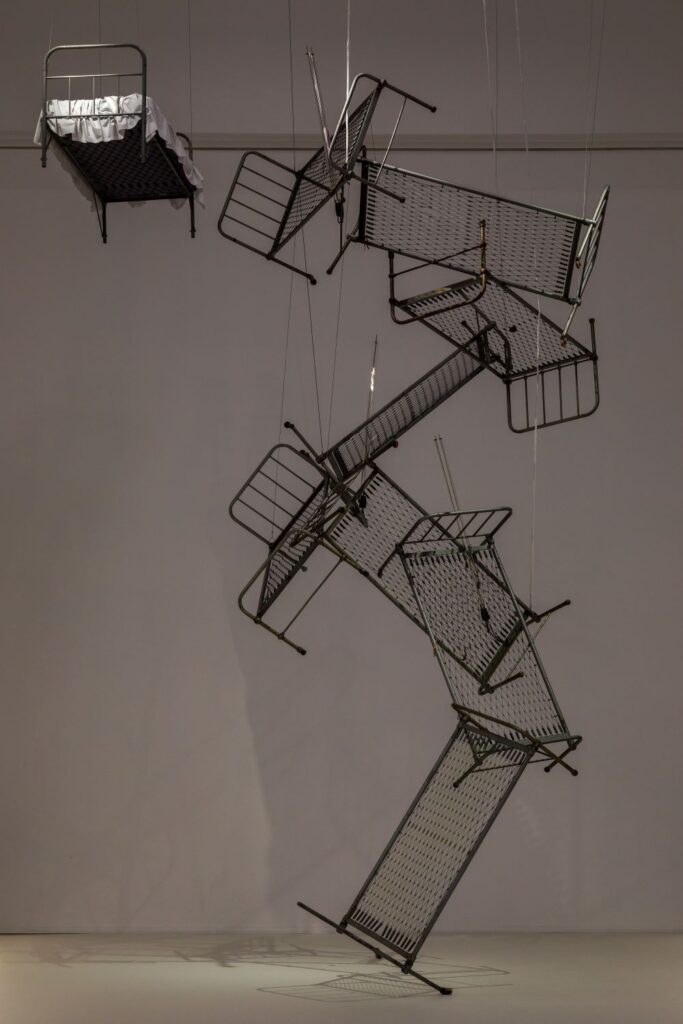

Inferno, 1993

In the 1990s, Horn developed characteristically immersive spatial installations, in which she deconstructs and restages music. One of the oldest examples is Inferno from 1993, an expansive installation of stacked hospital beds. The installation consists of metal bed frames from a psychiatric hospital wedged steeply into each other. Inside the towering structure of dizzying height, glass tubes fitted with electrically charged wires repeatedly light up as if in a lightning storm. The work is said “to be a multisensory, radical exploration of life’s mysteries, desires, dreams, pains, and abysses. For humans, the bed is a place of formative experience, from birth to death. Through the absence of bodies, Horn appeals to the power of imagination and calls for empathy for the suffering of others. The space as a whole thus focuses on the juxtaposition of the presence and absence of bodies, opening up between bodies and memory, bodies and vulnerability, bodies and technology.”

Tower of the Nameless, 1994

The Tower of the Nameless is Horn’s typical kinetic installation from the 1990s. Violins are mounted in a multitude of wooden ladders that are wedged into each other and seem to jut into nowhere. Motorized violin bows produce polyphonic sounds at intervals. Horn transforms the musical instruments into machines and at the same time gives them human capabilities, such as playing a concerto. Through this repetitive, multilayered violin playing, the machines are said “to express human emotions such as sadness and powerlessness”. The Tower of the Nameless is one of Horn’s most important works dealing with history and its catastrophes, such as war, displacement, and death.

Hauchkörper, 2017

In the recent installation Hauchkörper from 2017 twelve upwardly tapering brass rods, mounted on a dark steel base and mechanically driven, sway gracefully. “Their slow and asynchronous movements draw attention to time and its different perceptions, and create an almost hypnotic choreography. Physicality is characterized by a high degree of abstraction. Movement, like breathing, is staged as an invigorating force for human and nonhuman bodies. The work releases an energy which blurs the boundaries between human and machine. Whether Horn’s energy comes from human or mechanical movement, it is used as a force for transformation. This constant connects the early and late works in mystical, poetic, scientific, and performative ways. The exploration of connections with the environment has thus always been at the core of Rebecca Horn’s oeuvre.”