Not much imagination is needed to have a pretty good explanation of the human practical life. First we desire something (set a goal), then form a belief that by doing something we get what we desire, then put ourselves in motion, and then: go and get it. That (simplified as the model is) applies to almost anything that we do in the course of an ordinary day.

To explain what goes on in human mind is far more complicated. What fascinates our mind, often obsessively, deep down in each and everyone of us, what gets it going, and why, remains a mystery to outsiders. What bothers other minds can only be seen and experienced indirectly by looking at the results of the inner world functioning.

Not having a direct access to others’ inner world, and despite our helplessness and wordlessness in front of it, is no excuse for not trying to approach its creative achievements, particularly if the outcome is aesthetically as fascinating as with Anna Zemánková.

I did try. This summer in Switzerland, at the Museum of L’Art Brut of Lausanne. Always a great museum to pay a visit. One of its kind.

In Anna Zemánková’s (1908-1986) life the window opened up into her inner world when she was more than 50, had lost one of her sons and had gone through ”several bouts of depression”.

It is known that, deeply concentrated, Anna would begin drawing at about 4 am, and in a ”state of ecstasy” to capture the ”magnetic forces emanated by a parallel world”. For twenty-five years, she devoted herself to her artistic creation resulting in the production of several thousand works!

The Collection de l’Art Brut’s exhibition is the first major retrospective presentation of works by Anna Zemánková, many of the works being shown for the first time. The exhibition covers a selection of nearly 130 drawings assembled in close conjunction with the Anna’s family.

The exhibition is open until 26 November 2017.

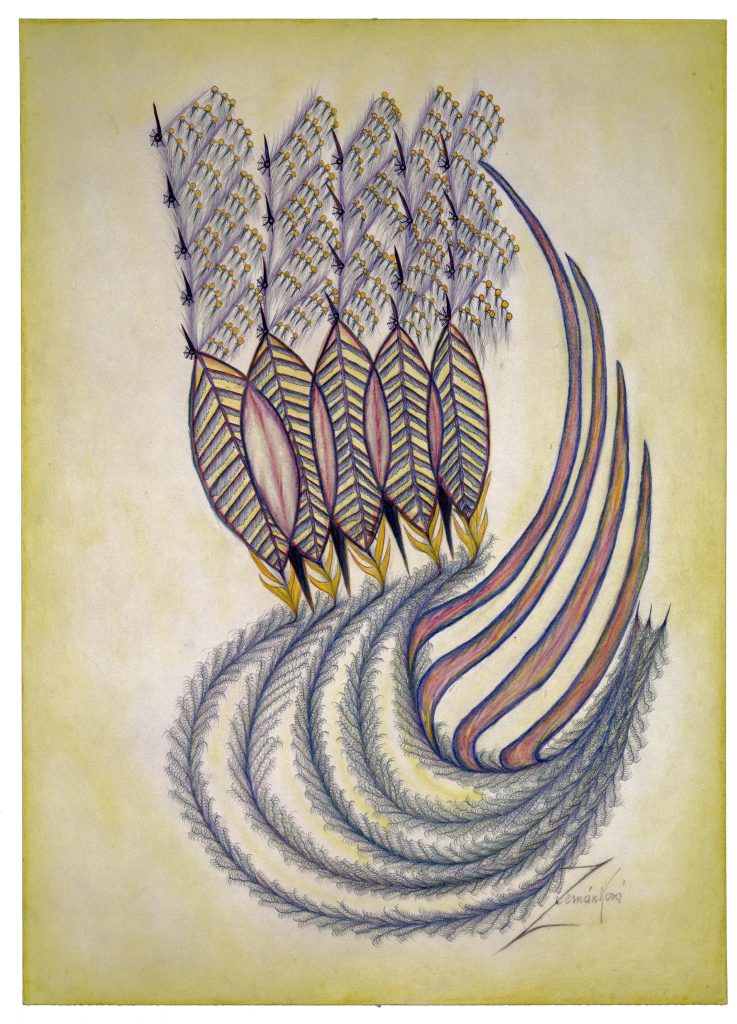

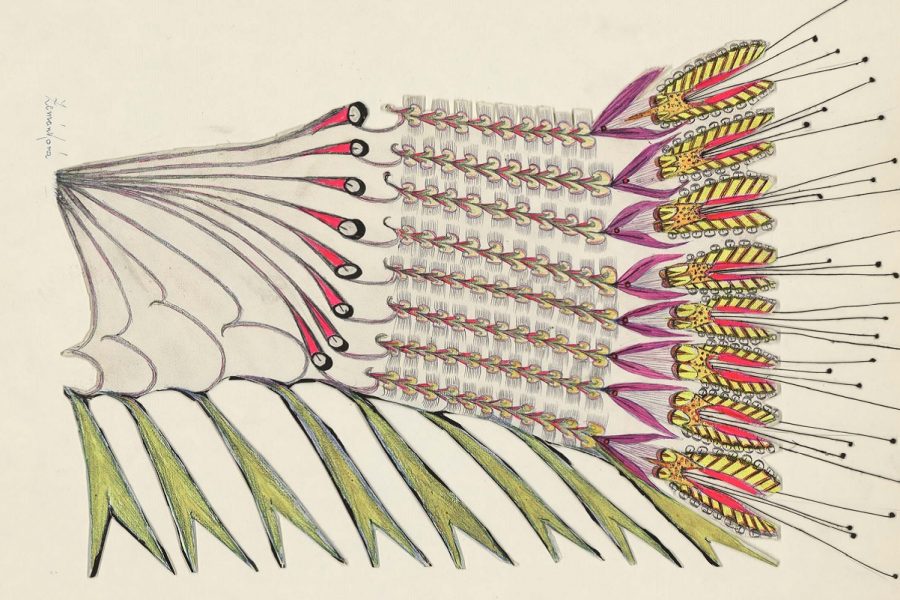

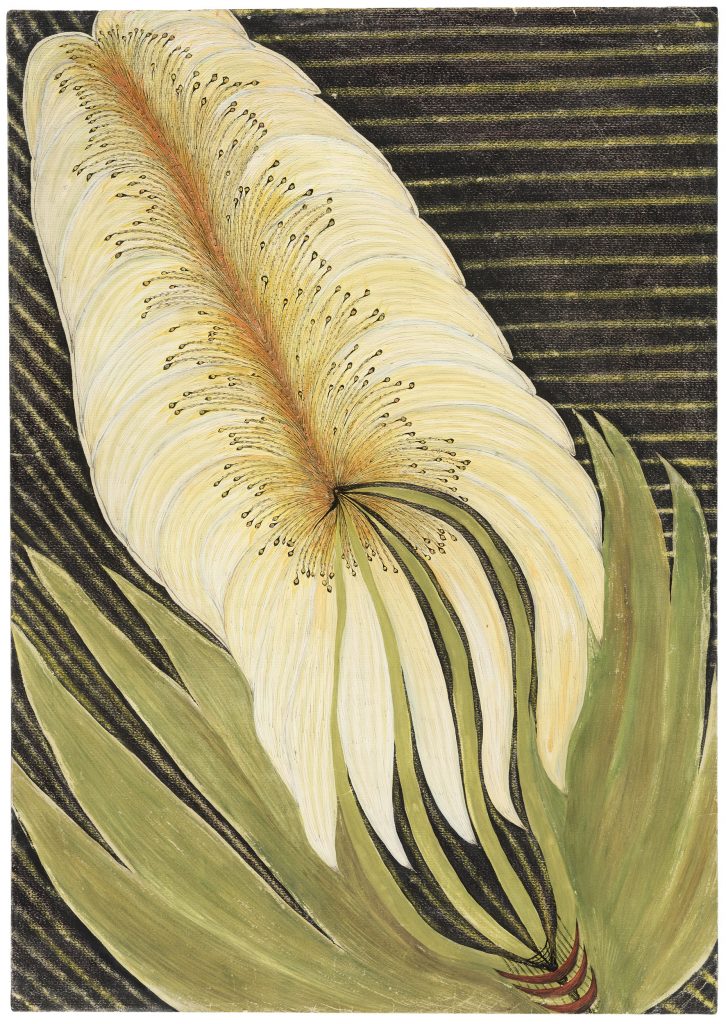

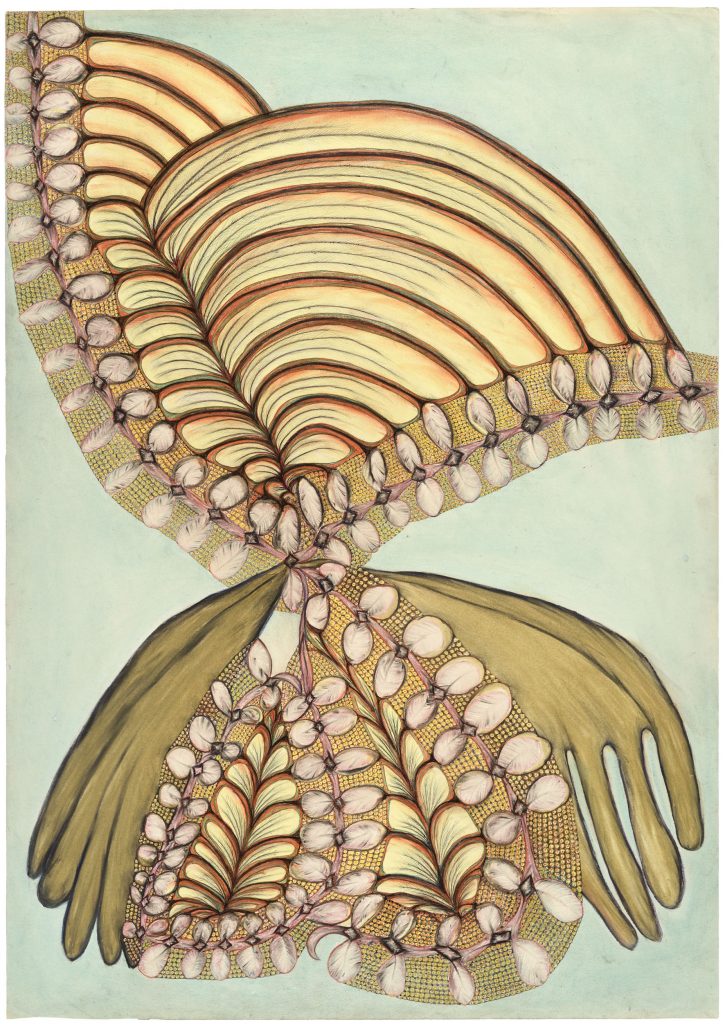

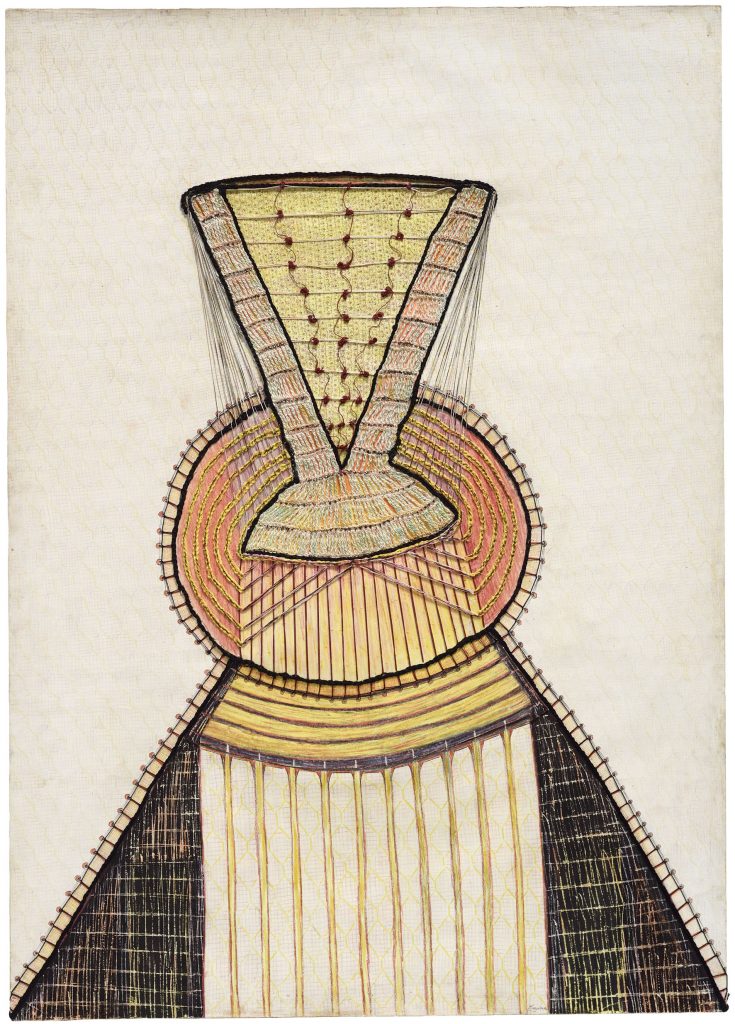

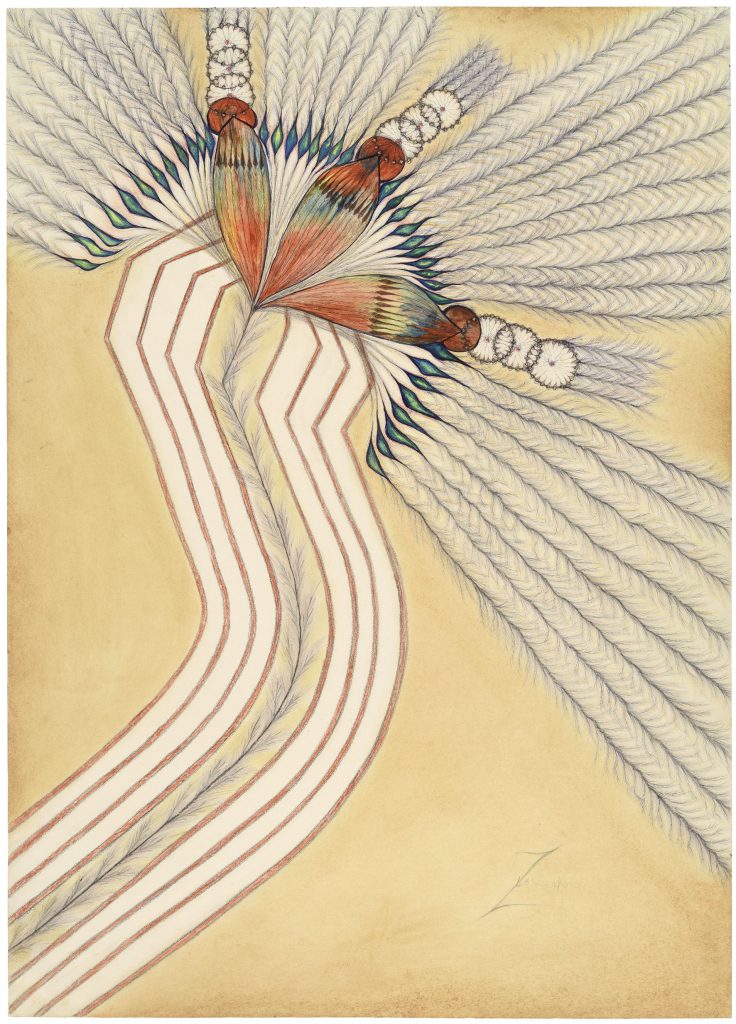

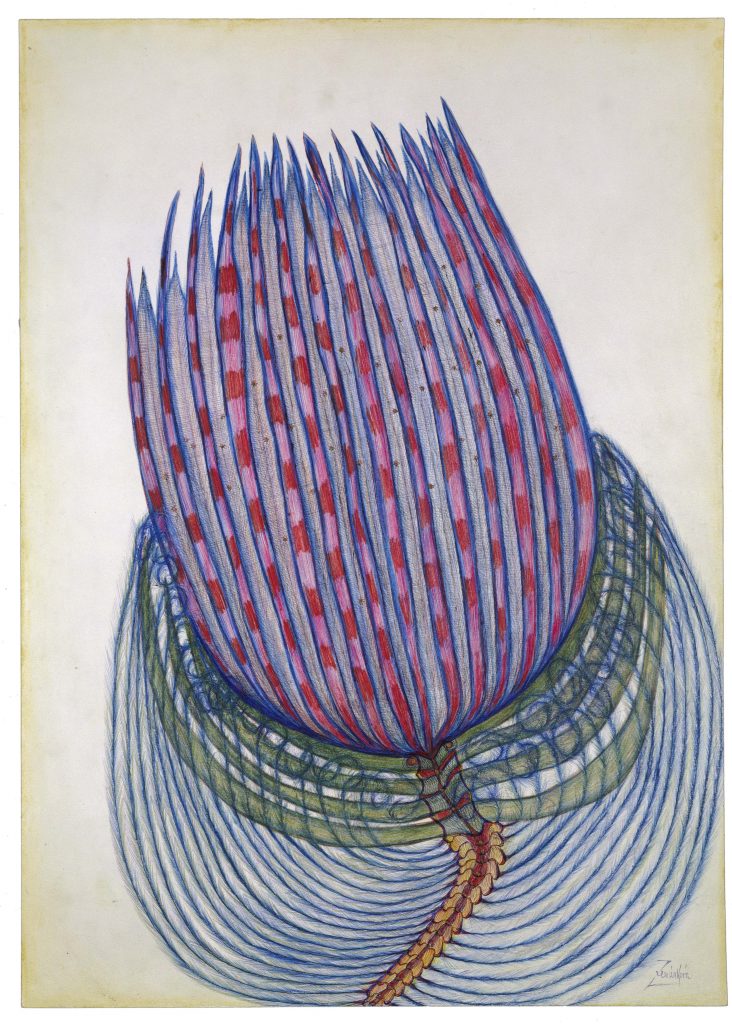

When I saw Zemánková’s works (large sheets of paper blending pencil, ink, pastels, perforation, collage, cut-outs, embossing and embroidery), and realized what they had required, physically and mentally, the encounter made me first stupefied, then humble. Perseverance behind all the works distressed me, even though it’s apparent that for the artist herself the parallel world to which the paintings permitted her to access, was more rewarding than the “real” world.

One could think that the admiration, say, toward all the marvellous landscape paintings of the Romantic period, with their magnificent details and painting techniques, and the atmosphere, would be similar to what one feels about Anna’s ”phantasmagoric herbarium of flowers and plants, all radiating in a blaze of colors”. But I’m inclined to think that the question is not, qualitatively and subjectively speaking, about the same thing or phenomenon at all. And the same is true of many 20th century more or less abstract paintings that on the object level come close to Zemánková’s style and image world. Anna’s works are not artworks in the same sense: their art comes from somewhere “deeper” (she had no plans, the motifs of her compositions emerging during the course of execution) and out of inner necessity. And the spectator feels it. This feature, of course, Anna’s works have in common with many other works that are displayed at the L’Art Brut museum, and that’s what’s so humanly great about them – in addition to their obvious aesthetic value.

Having married and settled in Prague, Anna worked as a dental technician before giving up the profession upon the birth of a second son. How many dental technicians, civil servants, shop assistants, guides, night watchmen, sales representatives, journalists, waiters etc. are out there with a similar artistic potential and zeal never having a chance to come true and flourish under the pressure of every-day practical life. Many.

PUBLICATION EXCERPT

Searching for roots of the work of Anna Zemánková

By Barbara Safarova, independant curator and critic

… Zemánková’s drawings do not seem to be inspired only by the floral and the vegetal; the inorganic element is present too in her hybridized objects. The inspiration in the inanimate is perhaps one of the things that connects her to the spiritualist artists of Nova Paka, drawing the so-called “metamorphoses“ during the spiritualist seances taking place in the 1920s. Some forms recall minerals in the gangue, which abound in the region of Nova Paka. Since the fourteenth century, those searching for precious stones and metals have come to this area to collect agates, jasper and amethyst. The soil also contains many fossilized animal and plant forms. When the gangue are opened, the stones cut and polished, the veins in the crystals become visible, revealing strange anthropomorphic or geometric motifs. We can get easily carried away by the magical beauty of these natural forms produced by the volcanic magma or by successive layers of silt, bringing us closer — at least in our mind — to the original matrix. Similarly to the terrestrial magma creating these wonderful stones, the automatic gesture brings out sprawling filaments, sometimes shaped into mysterious flowers or composite beings reminiscent of animals from far away times or planets. Zemánková’s hybrid motifs often seem to be composed from two radically different parts, glued to each other, without necessarily functioning as a harmonious whole. It is as if the artist were trying to transcend oppositions, above all the duality between male and female.

… Anna Zemánková’s artistic production is rooted in a number of cultural elements — secret doctrines, occultism and the Avant-garde — that would be regarded as contradictory anywhere else than in Central Europe. The Cubism of Central Europe, and more particularly the Cubism the way it developed in Prague, with the figures such as Bohumil Kubista, Emil Filla, and Otto Gutfreund, differs from Western Europe by the turbulent and magic atmosphere surrounding it; by seeking the expression of certain themes — suffering, death, religion — or by giving them a particular colour. The Czech Cubists are aware of not only Braque and Picasso but also of Orphism, spiritualism and psychoanalysis. Such particular syncretic experience results in works in which both magic and anxiety are present. After the Second World War, spiritualism seems to be less of an political obstacle than a possible escape from repression and from the communist attempt to impose a particular aesthetics. While rationalism dominates the political and economic landscape of post-war Czechoslovakia, some artists lean in their creation on their ancestral beliefs, combined with sometimes critical and syncretic return to psychoanalysis to escape Socialist Realism. Continuing to develop Surrealism — which did not lose anything from its intellectual appeal — artists, writers and philosophers consider the exploration of the subconscious as their true aesthetic program.

Exhibition Curator : Pascale Jeanneret, Curator with the Collection de l’Art Brut, and Terezie Zemánková, art critic and freelance exhibition curator