Human life is ruled by two deep/basic forces, two different aspects of the same, in itself positive thing. On one hand there is this contemplative Apollonian reason, and on the other hand, the emotionally oriented Dionysian life of pleasure and sensual attitude towards life.

The dichotomy between a rational soul, and a more advanced and passionate desire-life was already familiar in ancient Greece, but waves of the discussion have permeated the entire history of Western culture, through the centuries up to the industrial design from the end of 19th century up to the present day.

Normally the division is explained so that engineers, who support rational thinking and order (Apollo), emphasize both technical functionality and performance. Industrial designers and art directors, who give preference to sensual life (Dionysos), focus on hiding technology from the eye even when it could be kept safely visible.

Technology is ugly. As long as it has existed, it has been hidden: in the car under the hood, in buildings behind the walls and the boards, in watches under the clock face, in the home appliances, including sound reproduction equipment, by disguising the equipment as furniture or at least by fading away anything that refers to technology from the front panel. It takes a real male look to see in the innards of the device, in the actual technology, something aesthetically valuable, let alone beauty.

B&O’s own demons

A perfect example of the tension between the two ideals is the industrial history of Bang & Olufsen, founded in 1925. The dichotomy arose as early as in the 1930s, with B&O having to replace its aging walnut-shaped gramophone radio receivers, inspired by Art Deco and exoticism, with Bauhaus-inspired devices. Still in the 1950s, the B&O manufactured, from one and the same device, an everyday folk model and a more stylish model for architects.

An important milestone/landmark in this development was the Beolab 5000 amplifier from 1967, made for the nascent Hi-Fi markets in Europe. B&O set a demanding technical goal for the Beolab 5000: the amplifier had to be able to compete with the first professional stereo amplifiers developed by Scott and Fisher in the United States. Together with the Beomaster 5000 tuner, the package was marketed as “the world’s most complete Hi-Fi system”. And it did not fall far short of the target: The Beolab 5000 offered at the time an efficient and advanced 2 x 60 W transistor amplifier and the Beomaster 5000 a highly selective tuner.

But it was not enough. The products were not allowed to look as if torn off from the 19-inch equipment racks with at the time common front panel handles. So two award-winning industrial designers, Jakob Jensen and Davis Lewis, were asked to design a different, non-audio-like look for the amplifier, including many design features that reshaped permanently product design: really flat chassis, and slider switches familiar from the calculator in order to give an impression of precision hardware. The then industry standard, the gold-colored front plate, was replaced by an anodized gray aluminum plate. The handles were replaced by hex countersunk screws on the front panel.

The Beolab 5000 & Beomaster 5000 combo was a huge success. However, it did not remove the in-house tension between technology and more artistic concerns. The question of the primacy of either remained alive.

The last battle

The inevitable collision came five years later when B&O launched the design of the Beogram 4000 turntable. Karl Gustav Zeuthen and Subir Pramanik represented Apollo in the project. Zeuthen (1909–1989) was a prominent Danish engineer who, before joining B&O, designed and built the famous Kramme & Zeuthen (KZ) ambulance aircraft for Skandinavisk Aero Industri A / S. Subir K. Pramanik, on the other hand, was an engineer trained in India and England, and someone who was personally interested in turntables and especially cartridges. In order to test them, he developed test equipment and measuring instruments. Pramarik was also rewarded for his meritorious writings in industry journals.

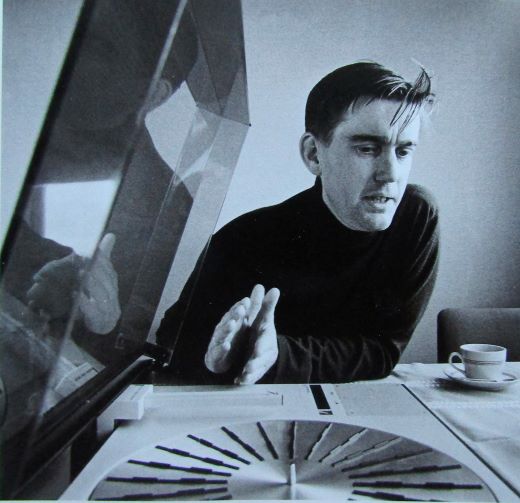

The role of Dionysus was handed over to Jakob Jensen, Denmark’s first trained industrial designer who represented modernism of the so-called golden period. Jensen did not follow the model of Bauhaus / Ulm-style rationalism, where form always follows function, or minimalism, where less is more, but relied on an international style that drew from American glass / steel architecture. He was also inspired by Raymond Loewy’s (1893–1986) MAYA style. The influences were merged by Jensen into his own ultramodern design language with the motto “different but not strange”.

Jensen’s design language matured during the 27 years (1964–1991) that he collaborated with Bang & Olufsen. It is largely thanks to Jensen that B&O changed from a Danish quality brand to an international icon. In him, B&O found itself. In all, Jensen was responsible for 234 B&O products, including such evergreens as Beolit 400, Beomaster 5000, Beomaster 1900 and, of course, the Beogram 4000 turntable.

From a small willy to a tune fork

At the peak of Beolab 5000’s popularity B&O decided to design a completely new range of products and at first, a turntable leaning on the same design principles as the Beolab 5000. As there were no skilled turntable engineer in the house, Zeuthen was recruited. He then did what he was asked to do and built a full-size, almost finished prototype in his garage, and which he was also prepared to show to B&O’s management.

Zeuthen’s own record player, Beogram 1000 from 1965, reacted to all vibrations coming from the floor. Therefore, Zeuthen’s first priority was to design a player that was effectively isolated from the outer resonances. He designed a floating subframe, for which Pramanik made the necessary mathematical calculations (including spring constants). The men also agreed on the tangential tonearm. For Zeuthen, it offered welcomed little inertia (an inability to resist movement) and for Pramanik, a cartridge without a tracking error.

Meanwhile, Jakob Jensen had drawn a modern-looking turntable with a long arm with a standard bearing. Jensen made no secret of his dislike of Zeuthen & Pramarik’s proposal. Especially its short tonearm looked awful to his eyes, it looked like “a small willy that doesn’t communicate potency”. The engineers stuck to their own proposal, Jensen to his own. The tension within the design team heated up to the point of splitting up.

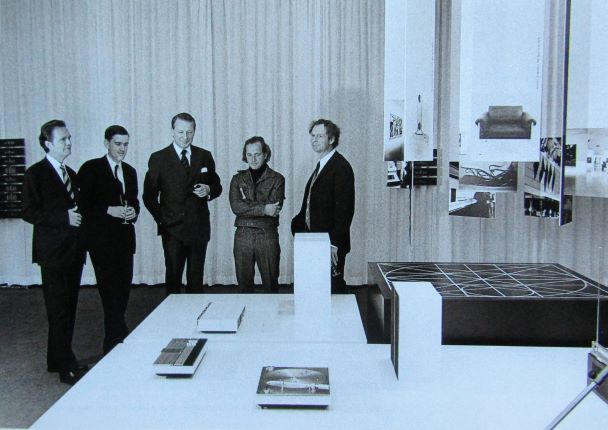

Product Design Manager, Jens Bang, the son of the B&O founder, Peter Bang, intervened and reformulated the assignment: “let’s not make a turntable for the little Hi-Fi camp who only uses it for testing their own equipment, but let’s make one that can best pick up music from a record groove.” Thus the target audience would be music lovers rather that ”fanatical Hi-Fi hobbyists”.

In practice, this meant that the technology developed by Zeuthen and Pramanik would be largely preserved but covered under a stylish top plate designed by Jensen. The tangential arm was allowed to stay as it picked up the music “just as it was engraved on the record”. Since there now were two short arms instead of one, the tonearm looked like a tuning fork rather than a little willy, so Jensen too could accept the solution.

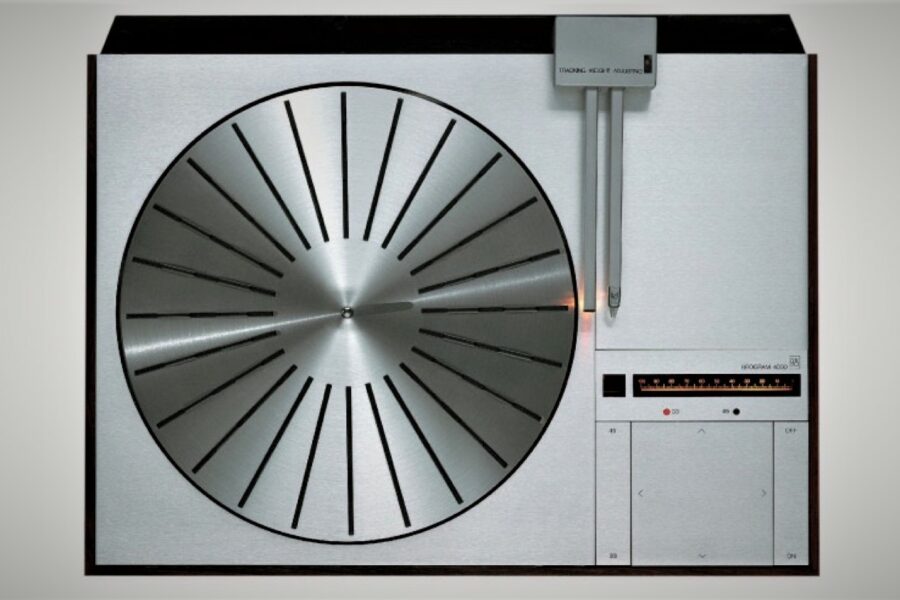

The double tonearm together with the control panel made the Beogram 4000 one of the market’s easiest turntables to handle, but just as important was its message: this turntable works completely differently than previous B&O turntable models.

Beogram 4000

Thus was born, in 1972, one of the most culturally important turntable of the last century, the Beogram 4000. If not the most important. It was reportedly also the world’s first record player with an electrically controlled tangential arm, but I’m not sure about that. The technically advanced turntable was also an extremely stylish and, eventually, an unprecedented commercial success.

After Beogram 4000, B&O was never the same!

The conflict taught B&O that competing with the Japanese and American audio manufacturers alone within the technical high-fidelity concept might not be its way. The episode deepened the spirit of experimentation and improved Jensen’s collaboration with Bang & Olufsen’s engineers. Thanks to all this, B&O was able to launch several commercially successful products in the coming years. The Beogram 4000 was also crucially important because the distinctive clear lines created by Jacob Jensen, its timeless simplicity and the grand style, made all Bang & Olufsen products easily recognizable well into the future.

Within a short period of time, the Beogram 4000 ended up in design museums and design books. It also won several international design awards between 1970 and 1990. The MoMa New York acquired one for its permanent collection in 1973, and later arranged a Design For Sound exhibition dedicated to B&O only. From there on, it was clear that Bang & Olufsen and Jakob Jensen had redeemed their place in the forefront of 20th-century industrial design.

* The information given in the article is mostly from the B&O company history: From Spark to Icon (2005).