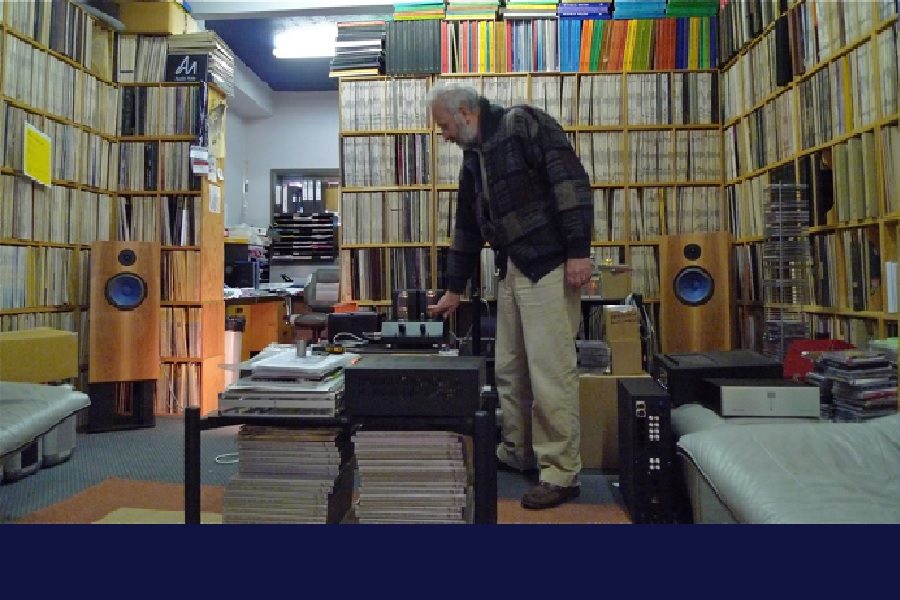

Audio Note UK participated in the 2011 Helsinki HifiExpo with a system comprising of AN-E/SEC Signature loudspeakers, ANJ UK’s Onkagu integrated, Level Five CD-transport and Fifth Element DAC, the AN-TT Two turntable with the new ARM Three and IoI MC cartridge, M9 Phono pre-amplifier, and AN-SOGON cables. Many were truly impressed by the performance, and the secret – and the price – of the sound was afterwards vividly debated.

Prior to the interview I had sent Peter copies of the latest Issues of Inner-Magazine (paper copy), and asked, as a starter, what did he make of Jules Coleman’s piece “Musical Value and Its reproduction” in Issue 6?

Peter: I have read and reread Jules’s piece, and it really asks many questions and answers none. He has clearly grown up in the sterile US audiophile environment, which alienates music from passion, enchantment and beauty, and tries to break it down into one-dimensional constituent components, detail, bass-midrange-treble, frequency, linearity, sound stage, imaging etc., none of which really describe in any meaningful way the musical experience, and his comments and views are clearly a reaction to that.

In essence I have no real argument with his overall aim, my problem with what he says is that there is absolutely no hints as to how one goes about achieving his stated goal, which makes the whole interview vapid and weak, and for someone who is clearly both eloquent, smart and literate that to me is baffling.

Inner: So what’s your own aim or method?

Peter: Well, we at Audio Note UK use a method that has been developed and refined over many years, called “Comparison by Contrast”. It involves the following relatively simple deduction: We really know only one thing about recordings and that is that they must be different, … that is, they have an individual character apart from the music on the recording itself, why?

Because every recording was done at a different time by different people, in a different location/room, using different equipment, microphones, mixers, amplifiers, cables etc. etc. every one of these differences will have left their “mark” in the sonics of each recording, and a good audio system or component should therefore be able to reveal these differences and thus differentiate the sonic individuality of each recording, this being the ultimate arbiter of quality. The less the equipment interferes with what is on the software the more of the individual character will reveal itself and differentiate the recording’s sound from that of other recordings. And the better the gear.

So rather than have a bunch of reference recordings, where you make assumptions about what is actually on the recording and thus make a biased judgement based on what you feel “what should be there” – or hear something that was not there before and assume it is more information -, we always use a few randomly chosen recordings, some good some not so good, and then make a judgement as to how well the system or component draws out the individual character of the sound of each of these recordings.

Inner: Right. That’s the theory part. Any evidence that your method also works in practice?

Peter: The inductive “proof” that this methodology works is twofold. First, it has allowed us to develop a product range where price and quality have a linear relationship, so that as products get more expensive they also get proportionally better, no diminishing returns here. It is easily demonstrated how the benefits of better materials, silver for example, improve the sound, giving it greater authenticity and believability. Since this method has guided our research and development program since the late 1980’s, it has helped build a deep understanding of what matters in audio design and what does not.

Secondly, we can also look at this from the recordings’ perspective. It is clear that the consistency achieved, for example, by DECCA with the Orchestra de la Suisse Romande, Ernest Ansermet conducting, or with their Vienna Philharmonic recordings, where they had a permanent set up that was perfected over many years, resulted in a predictable and consistently high quality of sound. More silver means that one can more quickly or more easily make this conclusion or how does it manifests itself. There are many other great recordings out there with a consistent sonic vision, and that can be clearly and unequivocally demonstrated by the Comparison by Contrast methodology.

Inner: “Easily demonstrated” …? How exactly is the listener supposed to know when the equipment interferes and when it doesn’t interfere, or interferes less than some other equipment? After all, the presupposition was that the only thing that the listener knows about the sound of a recording is that it’s different from another recording. The listener is not, for example, supposed know how “close” or “distant” the recording should sound, and use that info for his judgement of the sound quality. If I understood you correctly, in your method the listener somehow infers from the sound what is the correct mixed/ mastered distance or perspective of the sound? Intuitively that seems like a really tough task, given that it must be done without any prior knowledge of the disc. It seems that the listener needs to have at least some expertise in recording engineering in order to appreciate the Comparison by Contrast method? Do people understand and agree what is meant by “consistent sonic vision”, for instance?

Peter: This is where using a number of recordings is essential, as the differences between each recording … in some cases there are marked differences between different tracks on the same record as well …, we do not make a judgement in the way you infer, we simply make a judgement on how different the recordings sound, not how they were recorded or how the were mixed or balanced, all we look for is the extent to which they differ in sound from each other and the more they differ the better the system differentiates and highlights the differences, and what that allows the listener to do is appreciate the consistency of the sonic presentation of the recordings I mentioned above, which over time singles out the recordings which have a better and more satisfying balance and musical presentation.

Interestingly many of these are also more widely regarded as great recordings, but whilst these act as references to many people ultimately they do not necessarily make them ultimate evaluation tools when judging a system, as they generally sound good on most systems and therefore do not allow for critical evaluation.

Inner: Ok. So the fundamental difference between you and Jules is that you reference the sound quality, for the sake of “objectivity”, to recordings, whereas Coleman fails to see why the reference should be the recordings. Instead he wants to tie the sound quality to the system’s ability to be “musically rewarding”, engaging and immersive, which idea you find vague and baffling. Is that right?

Peter: Yes … I think Jules’s inability to formulate a clearer path to musical bliss reflects a view, increasingly popular in modern-day America and elsewhere, that everything is relative, based on personal experience and beliefs, and that nothing fact-based enters into the process and thus nothing can be guided by science, empirical or otherwise. In audio the spectacular failure of our “science” to square the circle between providing any consistently realistic musical experience with equipment that perform well under the steady state measurements that the audio industry applies to the design of its products, has undermined the validity of the science used, but no attempts have been made to develop a science that is closer to the sonic end results it yields. In other words, Jules’s position looks like a reaction to what he hears in the products that current scientific theory creates, more than any deeper philosophical insight into how one achieves a more musically satisfying experience.

Instead, our “system” works in every respect, one, as a design reference tool to determine whether a given circuit, component or system improves the sound or not, and two, as a way for a consumer to work his way through the maze of different equipment out there. This is in stark contrast to Jules’s aim or method, which allows you to claim preference for something without having any scientific basis for the claim. It could just as well make your car radio musically engaging, as it does not give anyone any idea what it actually means.

Inner: I think Jules would deny that a car radio, or his example Bose, could be musically engaging because even if it was, it would be it for wrong reasons! He wants that the listener’s reaction – the pleasure, joy or immersion – must be connected to musically significant and valuable features of the musical experience, and a car radio or a Bose simply cannot ensure the connection. Jules writes that an “audio system should help us gain access to those features of the music performance that define it as the performance that it is and which picks out those features of it that are musically significant and valuable”.

He doesn’t explain what those features are but an idea sometimes put forward is that the sound of an audio system should be particularly responsive to precisely those features of the performance that musicians have control over while performing the piece (dynamics, accelerations, tempo variations etc.), these being the features of the music performance that define it as the performance it is. Thus, a system that picks up these features would be preferable to Jules over those that don’t. This deviates from your approach in that here we have a short list of known sonic variables to be auditioned while evaluating an audio system. The features are not just reactively deduced from certain sonic signs buried in the recording. Is that right?

Peter: Jules is quite right stating that, it is important, but how does one achieve this? What is satisfying to him may not be what someone else is looking for in a performance, or what the recording engineer focused on during the recording, so whilst it may have some validity on some recordings an some system, it is highly unlikely to be braodly valid or relevant.

In contrast to this our method is the only one that has any possibility of achieving the essence of a performance across a wide range of recordings and music, precisely because it is value neutral.

Also, to say that a system should responsive to the features of the performance that the musicians have control over, what exactly does that mean for different musical genres, ranging from dub step, hard house, heavy rock, dance, electronica, death metal, drone or hip hop and so on where the instruments are more or less fully electronic when compared to acoustic instruments playing alone or in great unison in an orchestra?

Audio engineering is a very soft science, what Comparison by Contrast does is attempt to harden it a bit until such time when we are able to work out how to measure the differences we hear and create a technically more competent overview.

Inner: Supposing your method yields results that you say it does: brings forward differences between audio equipment in their ability to reveal sonic differences between individual recordings. Then what? How is the ability to differentiate the sonic individuality of each recording – the “mark” in the sonics – relevant to being passionately engaged and immersed in music? How the two are connected? For example, to be able to hear “consistency of the sonic vision” of a recording is hardly a sufficient condition for being “relaxed, rejuvenated, repositioned and reinvented” by music. Or is it? Your method looks like an intellectually rewarding exercise, void of emotion and passion, which mind-states Jules so highly values in audio. Am I missing something here?

Peter: Our method is not as “cold” as it sounds, because buried deep in the software are not only the clues to the way the recording was made but primarily how the music was played, which is exactly what I think Jules is trying to say when he says “musically rewarding”. A system that individualizes each recording not only differentiates or separates the sound of each recording but primarily digs deeper into how the musicians’ handle a given piece, and thus separates the great from the merely good in a way that relying on reference recordings generally cannot do consistently. Getting the maximum amount of information off the record most certainly includes all the musical subtleties that allow you greater emotional access to the quality of sound, depth of the interpretation and degree of musicianship on any given record.

What I think Jules is confused by is the need to find an alternative to the audiophile jargon – which I most certainly agree with – but in so doing he comes up with something that is also pretty unspecific and unusable as a way of achieving a repeatable experience with different recordings, which is what I think he seeks to achieve.

What we want to achieve is clear, an “inverted” version of the original event, whether a live take, such as a 78 transfer, or a multi-track studio recording, which once laid down on the software is the original.

Inner: That’s interesting. Could you elaborate a little on how and when in the process the “sonic subtleties” are transformed into “musically relevant details”? Because this I think is at the core of the issue. What Jules very specifically rejects, is not only to measure the system’s quality by its ‘fidelity’ to the recording, but also the common aspiration to excavate as much detail as possible from the recording. A Hi-Fi system is not a a microscope. A quote: “It is not obvious that the musical point requires anything like uncovering ‘details’; it requires uncovering musically relevant details. And not just as details, but as parts of a resolved musical whole. Something capable of conveying musical information, or expressing a narrative – in words or music or both.” It seems to me that what Jules is after is some kind of Gestalt theory of music reception, focusing holistically on “forms” rather than on individual details – whatever that means. And he doesn’t tell us what it is. But in view of this, it would be useful to hear more about how exactly your method “digs deeper”?

Peter: I think it is important to state that the system has no idea what is being played and therefore only responds to electrical impulses, it is the quality and accuracy of these electrical impulses that determines has closely a system converts the signal on the software to a musical experience.

Here’s an example. We once wrote an article “Your System is no Better than Your Worst Record”, which is based on the idea that using truly poor software, eg. mainly 78 transfers, where there is very little ”good” information for the system to “work with”, is a good test of how good it is at ”digging” out the musical message and separate it from the noise to make it intelligible. One interesting aspect of this test is how the greatest performers seem to transcend the medium even on the most appalling recordings, something that repeats itself on later analogue recordings, but which seems to get lost once we most to all digital recording media, a fact which then begs many questions about the homogenizing effect of the digital processing itself.

One of the most interesting aspects of using recordings like this is the way systems that are generally regarded as accurate completely fail to separate the music from the noise and in so doing largely fail to give a decent rendition of 78 recordings for example.

Inner: You said earlier that your method results in a sound that has more “authenticity” and “believability”. Those are highly metaphoric expressions as are “detailed”, “aggressive”, “solemn”, “transparent”, “dull” etc. Inevitable as these metaphoric descriptions are, I’m curious to know how “truthful” or reliable you think they are? Can we communicate some objective contents by calling a sound eg. “authentic” or “believable”? A signature can be “authentic”, and an excuse “believable”. But a sound?

Peter: Does the metaphoricity of the language not do the same for most other things as well, like the taste of food, wine and other such aspects of where our senses have to express what we are experiencing? I remember going to a demonstration put on by Riedel who makes some of the worlds better wine glasses and Peter Riedel used audio related metaphors throughout the demonstration to describe the way the taste of the wine changed in each glass, and for me these metaphors worked fine, but for some of the other participants they were less clear.

When we at Audio Note UK talk about the sound coming from a system or a component, I prefer to say that the sound has “medium”, “dynamic density”, “elasticity”, “authenticity”, “believability”, “immediacy”, “authority”, “evenness”, “colour”, “refinement” etc. I think the standard audiophile terms are mainly based around either sonic packaging, like imaging, sound stage and focus, or refers to pure frequency phenomena such as highs, lows, range, or distortive like harsh, bright, sharp etc.

It is actually quite obvious what is meant when we say “medium” or “authenticity” once you hear it. The problem is that generally very few, if any, systems actually draw these aspects from the recording, so it is like talking to the deaf in some respects. Once an Audio Note customer you will understand! He he!

Inner: “Obvious”?

Peter: “Obvious” is perhaps not the best choice of word, but as you said yourself language is actually quite impoverished in some respects. Basically, as I said before, the contrast method is a two prong affair, as it is meant to give customers a consistent way of judging the sound but it is also meant to give us the necessary understanding of which audio technologies do the better job, with a view to then study these to gain a better understanding of how they differ from the ones that do not, to explain why they yield better results, … this is really a lifetime project for me, and Andy Grove, to work out why, and as a result move audio engineering closer to be a “hard” science if that is possible.

Our belief is that many missing links in our understanding are hidden in what we hear but cannot substantiate through measurements, and if we can unearth some of these, for example why does silver sound so much better than copper, especially when wound into a transformer coil, because none of the measured data make that even remotely obvious, then there has to be something there that we do not know how to measure, and if we can find out what that is, then perhaps we can explain other phenomena in science, some of which we may not even realise exist yet, – who knows, we may be able to advance other aspects of science overall.

Inner: If what we mean by goodness in this case is “technical goodness”, then indeed it should not be too difficult to tell which gear is good and which better. But if what we mean by goodness, as I think we do, “goodness for some purpose”, eg. “good to listen to”, then chances to tell in some unambiguous way, which gear is good or better, are much less promising. The reason is the difficulty of giving an account of “good to listen to” that would be independent of who’s listening. It would be no use, for instance, to call together a group of experts to solve the problem. Your seem to hope that one day we managed to have an account of “good (better) to listen to” that would be entirely reduced to “technical goodness”. I just wonder if that is even conceptually possible?

Peter: The idea to create an alternative measurement system that more adequately describes what we hear is the end goal of this “effort”. But it is really not a goodness issue as I see it; it is a question of moving our understanding of the entire subject of audio engineering closer to the reality we experience when we listen to reproduced music, for good or bad the starting point has to be the recording, as that is all we have and by using recordings the way we do at least ensures a certain subject “neutrality” and removes or for want of a better word reduces the main obstacle, which is complete unbridled subjectivity, which is where the standard subjective evaluation system finds itself, as your paragraph below aptly states.

By current definitions, there are two relatively clearly defined schools, the “objective” school who bases quality on measurements and which denies that subjective differences exist and the subjective, which uses reference recordings and an everchanging mish-mash of equipment to try to determine what is better and what is not, according to both schools we should already have achieved better than perfection, a fact that makes reviewing less and less credible in the eye of the users.

At Audio Note UK we have different criteria. Comparison by Contrast method, of course, but we can also look at the history. One of my early thesis about audio was that the products that are highly prized now, this was in the early 1980s, were the ones that had certain inherent qualities. Nostalgia aside, only a small number of people will buy older products for that reason. So the products that survive and retain their value over long periods of time must have something that attracts enough interest to keep them worthwhile, and that is empirical proof that the technology used in these products has to be better sonically if it is more desirable over time. So a study of the technology in these products produced the idea that valve amplifiers were the best, hence my starting Audio Innovations as a starting point to study the technology in closer detail, and Audio Note is really only an extension of that, and with commercial success comes the financial ability to explore more deeply and expensively, of course, into the subject, but the reality remains that AN is as much a research and development engine as a commercial enterprise and I intend to maintain that “balance” as much as I possibly can.

And what I say above about history and time, applies to prized recordings and musicians as well. The problem with judging artists is that the ones that are flavour of the month now have a disproportionate “weight” when the panel passes judgement, whereas historical figures will not feature the way they should, because they are long dead and therefore not performing or recording anymore. For example, there is little or no debate amongst people who really understand and appreciate true performance quality that Caruso was the greatest tenor in recorded history or Casals was the greatest cellist, all you have to do is listen to some of their performances and compare to other later or current performances; however as recording starts proliferating, marketing has become ever more important and noise from the selling machine with it endless need for selling the new rarther than focussing on the best creates an ever increasing cacaphony of sales pitch favouring new, this in turn creates an illusion that we are moving forward, new is good old is redundant so to speak.

Meanwhile the cost of the music reproducing equipment keeps coming down since around the start of the 1960s, music becomes portable and suddenly is a consumarable rather than an artform and then the current artists increasingly take the limelight and history disappears into the memory of the history books or on the odd nostalgic radio program.

Eventually it comes round that the greatest music and the best products reproducing it go hand in hand in history’s gallery, and only a study of the performance styles and readings of the past can give us a real gauge of how good our current crop of performers really are, and it is the same with audio equipment, without this perspective, no self-appointed expert or expert’s opinion have any value whatsoever, and only really have use as yet another way of selling products of little value.

Inner: Ok, thanks. I still wonder why you are so against listeners’ having preconceived ideas about how the music should sound? Not sound but music. Following Glenn Gould’s train of thought, it could be argued that music is nothing but endless manipulation. Starting from the composers, eg. Bach, who revise other composers’ pieces for their own purposes, every link in the chain – the musicians, the technological staff etc. – participate in manipulating the end result. Why should the last link, the listener of recorded music, be disallowed to carry out his or her own manipulation of the sound along the lines of his or her preconceived ideas about how the music at hand should sound? Isn’t that what audiophiles’ sophisticated playback systems are fundamentally for?

Peter: Of course music is a sophisticated form of manipulation. It is also true that it is a fine form of emotional and intellectual communication that transcends any language, but does that not also mean that we should not try to make a piano sound like a piano or attempt to achieve a level of ability to differentiate between the intonation of Gould’s finger work, which is critical to understanding his particular view of the music he is playing? Ultimately an audiophile can manipulate his/her system as much as they like, but does that mean they can claim their system reproduces the full potential of each recording in their collection?

I think not.

Which may explain why the neurosis surrounding “upgrading” is so pronounced, I have customers who have owned the same component 3 or 4 times, each time in the belief that they missed something last time rather than realizing it was some other part of the system they were hearing, which caused them to change. Of course this is perfect for an industry, which also has no idea, which direction it wants to go, apart from one that pays the next month instalment on the new Porsche!

Inner: You care about the “full potential of a recording” because the reference to you is the recording. But I assume that those who take the manipulation idea seriously do not care so much about the recording but of how the music sounds. For example, I like the idea that my system does not have a sound, because it has many sounds, depending on how I decide to manipulate it. If Joni Mitchell’s voice and guitar appear under-represented on a particular track, I go and fix it – easy with an active system. Or if the bass line in some baroque music sample needs strengthening, I strengthen it. For some reason I find most recordings of Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden” inadequate, and therefore manipulate the sound as I feel is essential for listening this particular music. Why should we take the view of the sound engineers at face value? They have their ideas of how the music should sound, I have mine, and I’m the king in my listening room. In the end, it’s Bach that I want to listen to, not Glenn Gould or some sound engineer. Is this unacceptably subjective or solipsistic to you?

Peter: That is off course correct, you are free to change what you do not like, however, I think most music lovers would prefer a system that makes a sufficiently good job of 85% of their records, rather than trying to correct a recording to the balance you prefer, in which case you are no better than the recording engineer.

The fact remains that all we have is the recording and using that as the basis is the only logical thing to do, we can fantasize as much as we like about how much better it would be if we could have the live performance in our living room, but that will never happen, so we depend on musicians to play and recording engineers to record their efforts, we can supplement this by going to live concerts, but again i may feel like listening to some Slayer and all there is playing at the local halls is a quartet or a jazz band, so I have to resort to listening to a record or CD with Slayer, for good and for bad.

As far as listening to Bach – or Chopin, or Cesar Franck – , and not Glenn Gould or his recording engineer, unless you invent a time machine sometime soon, there is no way you will ever achieve that, to me it is a benefit, as it allows me to listen to a wide range of performers playing Bach and each of them bring an interpretation to the piano which give me a different perspective on the same music, just as Gould does, whether one then prefers one performance over another is a matter of taste and has little to do with the sound itself.

Inner: Your ban on using selected reference recordings brings to my mind the practice of the French Hi-FI magazine “Nouvelle Revue Du Son”. They release regularly Disque Test with music samples, mainly classic, chosen by Jean Hiraga and his team for the purpose of checking certain aspects of the sound quality. For each sample, they tell exactly what to listen to (1-3 variables) and exactly when: a piece of lute music for evaluating the nature of attacks, two closely recorded violins for detecting HF aggressiveness etc. They tell explicitly what happens if the system/room interferes in a wrong way, and how the sound would be if the system did not interfere in a wrong way. I guess they feel justified to make these claims because they’ve accumulated massive empirical evidence over the decades. So contrary to what you say, it seems possible, if cleverly executed, to use reference recordings, of which one can reliably assume how they ought to sound? I’ve found some of their test CDs useful and informative.

Peter: Well there is not necessarily anything wrong with that mainly because a good recording generally always sounds better, even on a lousy system, which may explain why most systems I have ever heard set up by Jean Hiraga and Patrick Vercher sounded thoroughly dreadful. Reference recordings “pull” in different directions, so depending on the system used at any given time, if you take several of these reference recordings, the comparison by contrast system will show you that Jean & co used different equipment each time they decided on which pieces to include on each issue.

Can I close this interview with one of my favourite quotes?

Inner: Please, go ahead.

Peter: It is by the author of Discworld, Terry Pratchett, and goes like this: “Reality is not digital, an on-off state, but analogue, something gradual. In other words, reality is a quality that things possess in the same way that they possess, say weight.” I really like this way of expressing the difference.

Inner: Thanks, Peter, so much for this interview!