Right now, as I’m writing this piece, in millions of homes around the globe, passive dynamic loudspeakers are driven by low output impedance audio amplifiers. The lower the impedance, the better, says conventional audio wisdom. But is it?

Here’s what’s gets wrong. Think, as Robin Audio does, of a dynamic loudspeaker as nothing but a voice coil suspended by springs (that’s what it essentially is), the whole mathematically described with a complex impedance. The voice coil moves (i.e. the cone accelerates) only when current passes through it. When an electrodynamic element is driven with voltage with a low output impedance amplifier, that complex impedance converts voltage into current, and like Esa Meriläinen has indisputably shown in his book, the conversion is far from linear (see. Esa Meriläinen, Current-Driving of Loudspeakers – Eliminating Major Distortion and Interference Effects by the Physically Correct Operation Method, 2011. The book is still perhaps the most comprehensive work on the disadvantages of voltage control, and advantages of current control of loudspeakers.).

Why? Because when a dynamic speaker is voltage controlled, indeterminate electromotive forces induced in the voice coil can freely distort the voice coil current. Part of these uncontrollable EMF factors impairing the voltage/current conversion appear in the distortion measurements, part as other harmful factors. When the speaker is current driven/controlled, no internal voltage/current conversion is needed.

No matter. The loudspeaker industry has not warmed up for current control, one excuse being that there are no suitable drivers for it. The trouble can be circumvented by building a loudspeaker, as Esa Meriläinen has done, around a conventional dynamic driver (Scan-Speak 15W/8434G00) but by using a series impedance and a step-up transformer, enabling the use of a small output impedance voltage amplifier (the speaker is introduced in Meriläinen’s book). However, nothing prevents one from building a true current-controlled loudspeaker, and that’s exactly what Philippe Robin has done with his Oloron series of loudspeakers.

Philippe Robin, an engineer from the French Riviera, knows Esa Meriläinen’s book like his pockets, as well as relevant papers eg. by Mills & Hawksford and others. One day then he decided to put the wisdom of the books into practice and build his own loudspeaker. Thus was born the 100 kg 2-way active speaker Oloron Classic with a built-in-house 350mm coaxial driver in a large spherical cabinet full of digital technology. The experience gained from the Oloron Classic, and the feedback received, inspired and encouraged Robin to build a series of more practical and commercial speakers. This resulted in three box speakers of different size: Tenor, Monitor and Domino, in order of magnitude from largest to smallest. Let’s focus on the smallest: Domino.

OLORON DOMINO

Domino is 36,5 cm high, 27,5 cm wide, and 13 kg two-way active speaker with the manufacturer’s own 200 mm (8-inch) coaxial driver in a 12 liter sealed cabinet. It’s a two-way because, according to the manufacturer, the best dynamic woofers can work nowadays easily also in the mid-range, and when correctly implemented, a 2-way speaker is sufficient to cover all the 10 octaves of music just like multi-ways – but at lower cost. The driver is coaxial because for Philippe Robin, just like for many other French audio enthusiasts, a coaxial driver is still the best way to emulate the theoretical ideal: a full-range point-source widebandwidth speaker (ie. one-way).

And Domino is closed/sealed because bass reflex, despite its popularity, produces an “uncontrollable bass response”, which according to Robin should have nothing to do with Hi-Fi speaker. For him, the movement of the woofer cone can only be controlled accurately enough in a closed cabinet. For those who hesitate, Philippe Robin recommends Grimm Audio’s Robert-H Munnig Schmidt’s article “Why Bassreflex is not Suitable for Low-Frequency Musical Sound Reproduction” from 2017 (available on the net). The article resembles Esa Meriläinen’s book in that it shows how loudspeaker industry, for purely commercial reasons, works against better technical knowledge.

COAXIAL ELEMENT AND AMPLIFIERS

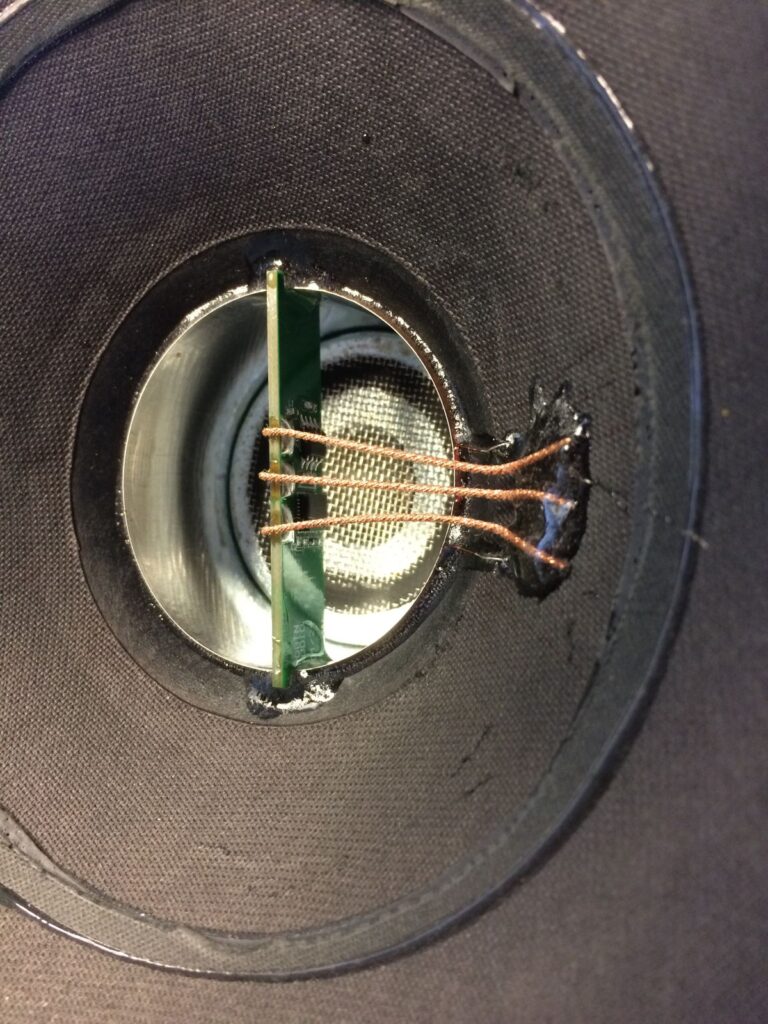

The woofer of the Domino’s coaxial driver is Beyma 200mm 8BR40/N with a ferrite magnet and a 25.4 mm copper voice coil. The tweeter is Beyma 32mm T-2030 aluminum dome with a ferrite magnet and 60º waveguide. The tweeter is set concentrically in front of the woofer with a thick grid, and its signals are digitally delayed in relation to the woofer. The crossover frequency is around 3 kHz, but there is no conventional passive crossover filter. Amplifiers ‘see’ the drivers directly while the electronics dose the power precisely for both drivers in order to maintain the response uniform and even.

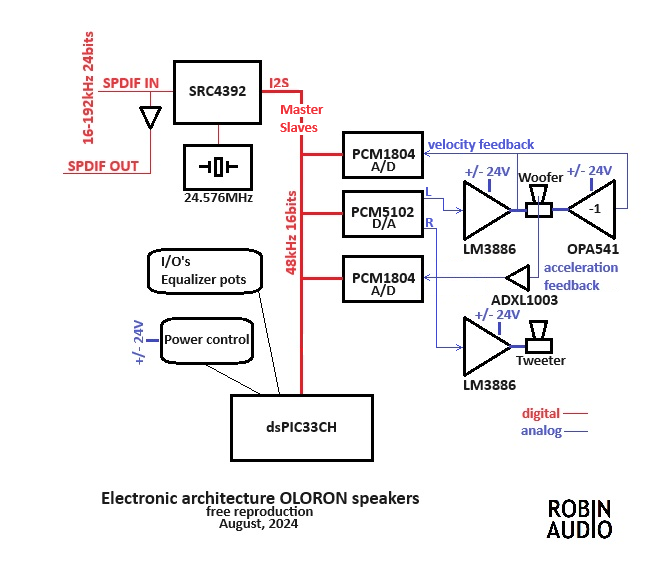

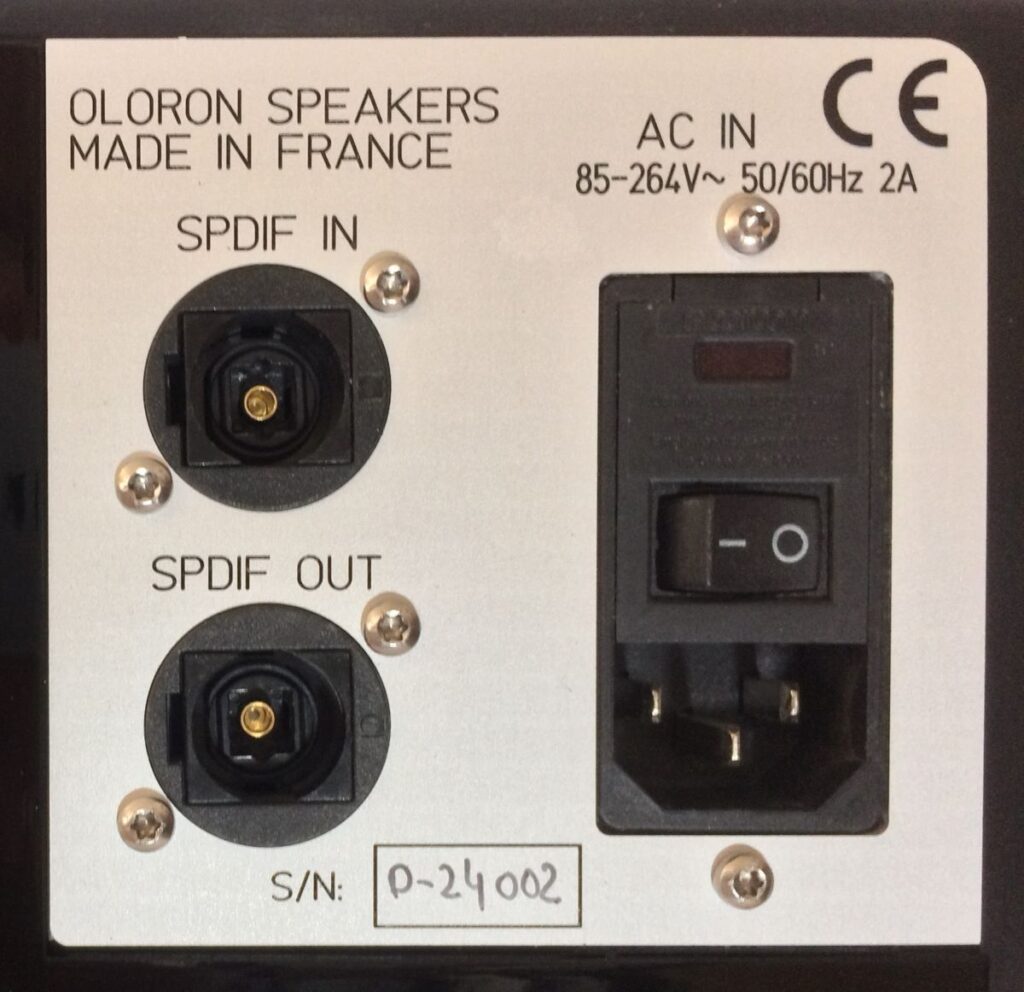

When removing Domino’s backplate (I didn’t and you shouldn’t either, but look at the image below), things become exciting. Behind the cooling elements the eye meets first the heart of the speaker: a multi-core digital signal controller (Microchip dsPIC33CH) with efficient DA/AD converters and and other digital peripherals. Incoming audio signal is optical SPDIF only.

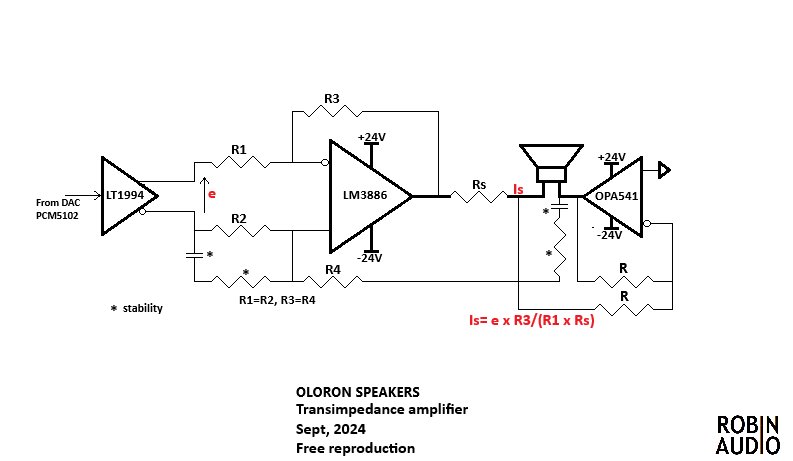

Then come the current drive transconductance amplifiers. They are built around, in itself a simple but in practice not that easily implemented, Modified Howland Current Pump circuit (Texas Instruments, Application Report AN-1515) consisting of operational amplifiers and resistors, in Domino’s case, Texas Instruments’ linear Class AB LM3886 microcircuit and standard adjusted 0.1% resistors. The same could have been realized discretely, but Robin didn’t see any good technical reason for that. According to him, the output impedance of the amplifiers never drops below 40 ohms.

For the woofer, there is an H-bridge, the LM3886 on one side, and on the other side, a traditional operational amplifier (OPA541) to increase power and improve compatibility. The output power of the amplifier for the woofer is said to be about 50 W and 15 W for the tweeter. With this power reserve Domino is claimed to produce about 100 dB SPL to the distance of one meter.

Here’s the whole architecture:

MOTIONAL FEEDBACK

Current drive takes care of the treble response and distortion, but to control the woofer behaviour is a way more difficult when approaching the resonance frequency. Meriläinen solved the problem by constructing a closed rear labyrinth to his speaker. In the Domino’s case, the bass resonance is controlled with a help of a digital feedback loop, including both the acceleration signal (Analog Devices’ ADXL1003 accelerometer) and velocity signal. The accelerometer recognizes the acceleration of the voice coil/cone, which information is sent to the feedback loop accompanied by the audio signal. The difference/error signal is fed to the amps controlling the woofer. The method is familiar from Philips 1970s Motional Feed Back (MFB) speakers.

Motional feedback reduces distortion (according to the manufacturer at worst: 1.5%/92dB at 75Hz), but also transfers the resonance frequency, in a closed cabinet, half an octave lower while the velocity servo levels the resonance peak. Domino’s woofer response is further adjusted with the equalizer for the first two octaves, as is the treble response (two highest octaves) in order to compensate for the increasing impedance at the tweeter voice coil.

DAISY CHAINING

Two Dominos are connected as a stereo pair digitally with an optical SPDIF cable. For those whose digital source doesn’t feature a volume control, Robin Audio offers a small control box designated as Channel Selector, with volume and channel balance adjustment plus four digital inputs (mini-XLR, optical SPDIF, mini-USB, Bluetooth). The fact that inputs are digital only is Robin’s conscious choice. Domino was designed with the ethos that what fits for the needs of professional sound reproduction, is, as a matter of principle, also suitable for amateur audiophiles.

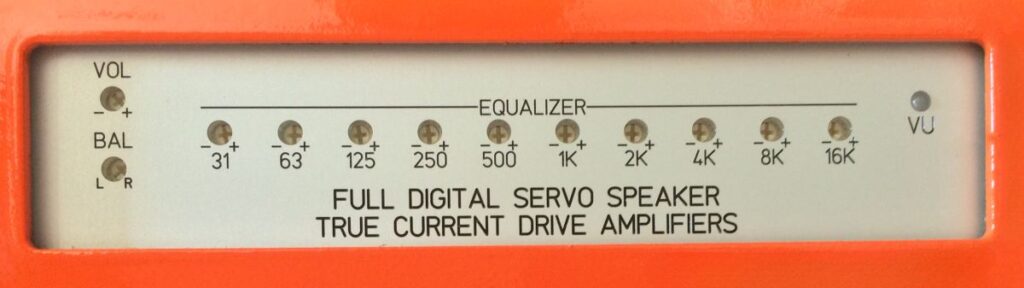

The selector box is connected to one of the speaker (doesn’t matter which one) with an optical cable. From the small front plate trims the user chooses the channel (left/right) and the local volume control is set on the max position. Using Domino was trouble-free. All inputs worked as expected. I could have made use of a remote but I realize that it’s my vanity. The speaker cuts itself off fairly quickly when detects no signal, but also comes back to life in a few seconds. The idle power consumption is 1.5 VA, so no no bankruptcy if left on.

For the audition, I placed the speakers more or less as the manufacturer recommends, i.e. either listened on axis or just a little off-axis. Marrying a small tweeter with a relatively large woofer will inevitably result in off-axis responses starting to drop early on. More off-axis and, for instance, human voice becomes colored. The directivity of the Domino is something Philippe Robin was well aware of. He is, however, strongly of the opinion that whenever the assumption is that the listener(s) stays still in the spot, a directional speaker is the winner, whether in a studio or at home. As he puts it: nobody needs Hi-Fi speakers for dancing and partying!

In the same manner, I didn’t touch Domino’s front panel 10 band EQ (31Hz – 63Hz – 125Hz – 250Hz – 500Hz – 1kHz – 2kHz – 4kHz – 8kHz – 16kHz) digital EQ (-60dB .. +12dB), because I didn’t want to manipulate the frequency response selected by the manufacturer (also, the trims could have been a tad bigger). But I do like the idea of Domino’s manual EQ. After all, it’s the ear that is often the ultimate judge for telling what’s wrong with the sound of that particular music. But as said, I kept the trims of the equalizer in their zero position because in this speaker the EQ is the nerve center and fully responsible for the tonal balance chosen by the manufacturer.

LISTENING IMPRESSIONS

Although I firmly believe that the richer the descriptive vocabulary of the reviewer, the better s/he hears and understands the sound (that’s because ‘sound’ is not a property of ‘air molecules’ that cause it, but depends on the sense impressions/sensations that it causes in the listener), in the Domino’s case I want to keep the subjective description succinct in order to focus on what this speaker does so well.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the Domino’s sound is its purity from bottom to top. This purity should not be confused with what I assume is generally meant by loudspeaker ‘transparency’, which probably has more to do with the characteristics of the speaker’s frequency response. The purity in the Domino’s case means, for one thing, that the speaker has quite an exceptional ability to make clear, a layer after layer, not only what’s happening on the front of the stage of the orchestra, but also on the back stage, in the second and third rows. I find this level of ‘see through’, that is, the ability to make small and distant sonic cues audible, rare, and it reminded me of my tentative impressions regarding Meriläinen’s current driven loudspeaker years back (so perhaps it has to do with current drive and lack of harmful EM effects?) When extra obscurity or haze – I don’t know exactly what to call it – has vanished from the surface of the sound, the listening experience turns more informative and meaningful. Music makes more sense, simply.

The purity equals to more music/sound going into the speaker, including dynamic and complex one. First week I spent by listening solely to classic music on dozens of decades old Nouvelle Revue du Son Test CDs. One of my amusements was playing back the most dynamic/complex samples of orchestral music that I could only find, and do it at rather high volume levels. Apart from a couple of extreme exceptions I did not feel that there would have been too much material for the Domino to chew up. The sound remained clean and sensible throughout.

The second praiseworthy feature of the Domino’s sound is its bass performance (the manufacturer claims -2dB / 52Hz and 40Hz, +/-3dB). One way to formulate the idea here is this: Domino dares to sound mid-rangy. It sounds mid-rangy whenever there’s nothing else on the record than midrange content, but lo and behold when the record really contains mid and upper-bass notes, the speaker reproduces them as they should and without pushing them into the lap of the listener. To me that’s always a mark of a quality speaker. The bass is springy, as it often is from a sealed cabinet (and BR rarely is), but I felt that the Domino took things a step forward in this respect. The Domino doesn’t necessitate a subwoofer but after listening to it for a longer period of time, I became tempted to hear one of the two bigger sister models, Monitor or Tenor. Not so much because of their lower Fc (e.g. Tenor: 25Hz/104dB@1m), but more in view of the general breathability of the sound.

Thirdly, there is no distinct treble to pay attention to. This presumably results from how the sound of the woofer and the treble have been cooked together. Most coaxial drivers excel in this regard to some extent, but there are differences as well. In the Domino’s case, the speaker paused me to think more than once that, compared to conventional 2-way box speakers with two drivers mounted onto the front panel, the ear always senses the presence of a separate tweeter in one way or another, regardless of how meticulously the crossover have been realized, and all other things being equal.

So how was the sound overall? Did it have any characteristic color? Given that the Domino was sculptured to sound like a monitor speaker in a studio, the presumption naturally is that the sound lacks any recognizable color. But since we’re dealing with mortal objects here, the Domino cannot escape of having some sonic qualities of its own; and when it’s does, it cannot be its opposite. For example, although it exudes monitor-like neutrality the Domino ain’t a BBC LS3/5 type of monitor. Not at all. It puts what’s on the record before how pleasing the sound is to the ear. At the other end, some monitor speakers pretend neutrality by sounding raw and metallic, and the Domino isn’t one of these monitors either. The sound of the Domino simply lacks an easy appeal factor, and that’s what makes it so appealing. Very consisting and confident sound. It may take a little while to understand what’s the name of the game here, but once you’ve got it, it’s hard to let go.

SUMMARY

All in all, Domino is a fully digital (dsp 48kHz/16bit) 2-way active speaker with a current driven, motional feedback/servo controlled 8-inch coaxial driver in a closed cabinet featuring a 10 band digital EQ. As such, it’s a highly unusual loudspeaker. It may not be for everybody for it preconditions certain things. It preconditions that one should not listen to it from another room or just in the background. And once you’re stand still in the spot it recommends kind of nearfield listening in which the speakers are directed more or less toward the listener. And for the owners of RIAA-preamps or FM tuners (typically with analogue outputs only) it is of no use. But if and when one accepts the boundary conditions, the Domino is able to offer a sound that has many truly rewarding factors.