Don’t feel embarrassed if, when watching this loudspeaker, you think what you see is a design speaker. It certainly looks as if it were a design speaker, and your belief surely would be justified in view of the fact that the speaker ended up being an item in the MoMA (NY) permanent collection as well as in half a dozen other design venues all over the world.

The name of the speaker is Gradient 1.X. The X can take the value of 0, 1, 2, 3 or 5, depending on the model – the 1.4 was launched just a few weeks ago. The 1.0 – 1.3 have nothing in common with what we commonly understand by a design speaker. It’s born solely out of acoustical concerns, not aesthetic. Every corner and edge are dictated by reason. Every form you can see – round, oval, square, rectangular, pillar – slavishly follow a strictly predetermined function.

Gradient do occasionally refer to the contribution of the industrial designer Jukka Vaajakallio who did design, for example, Gradient Avanti speaker. But when it comes to the Gradient 1.2 or 1.3 he’s role was limited to giving his blessing to the acoustic design and trying to save what could be saved within the given strict limits.

The cylinder bass cabinet of the 1.3 looks like a design element but the use of the cylinder shape, rather than the box of the 1.2, was well grounded from the technical and engineering perspective. Plus, and even more importantly, it was much more convenient and durable to stand hardships of transportation.

The Gradient 1.2 and the 1.3 look as they look after a number of technical solutions have been applied to them. When the founder and head designer of Gradient Labs, Jorma Salmi, was once asked what prompted the visual design of the 1.3, what are the aesthetic principles behind its shape and form, Salmi responded: “There are none.”

The fact that they look like a robot is accidental, not planned.

What then are the true reasons for the cheerful outlooks of the Gradient 1.X speakers? To answer that question is greatly facilitated by the fact that very rarely the reasons for the shape of a loudspeaker are so unfolding and explicit as in this case. But lets not put the cart before the horse.

All loudspeakers sound equally well

Everyone may not remember Gradient’s famous experiment in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The experiment, the results and the interpretation of the results were presented in the AES Paper No 1871, 1982, co-authored by Salmi and Anders Weckström.

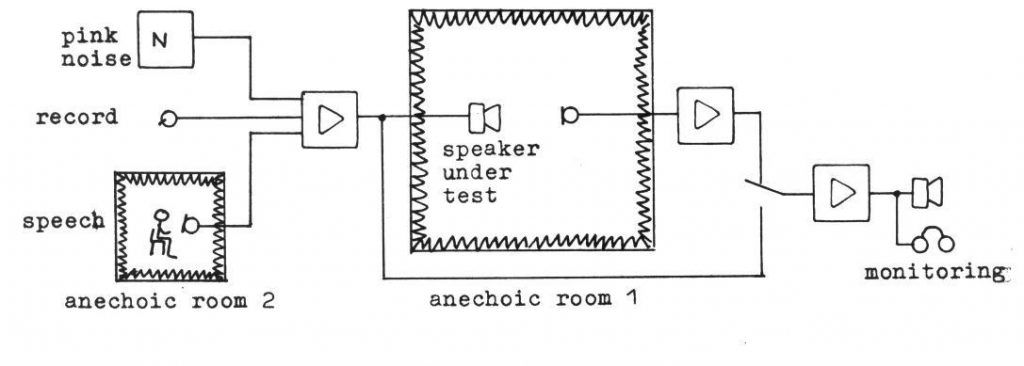

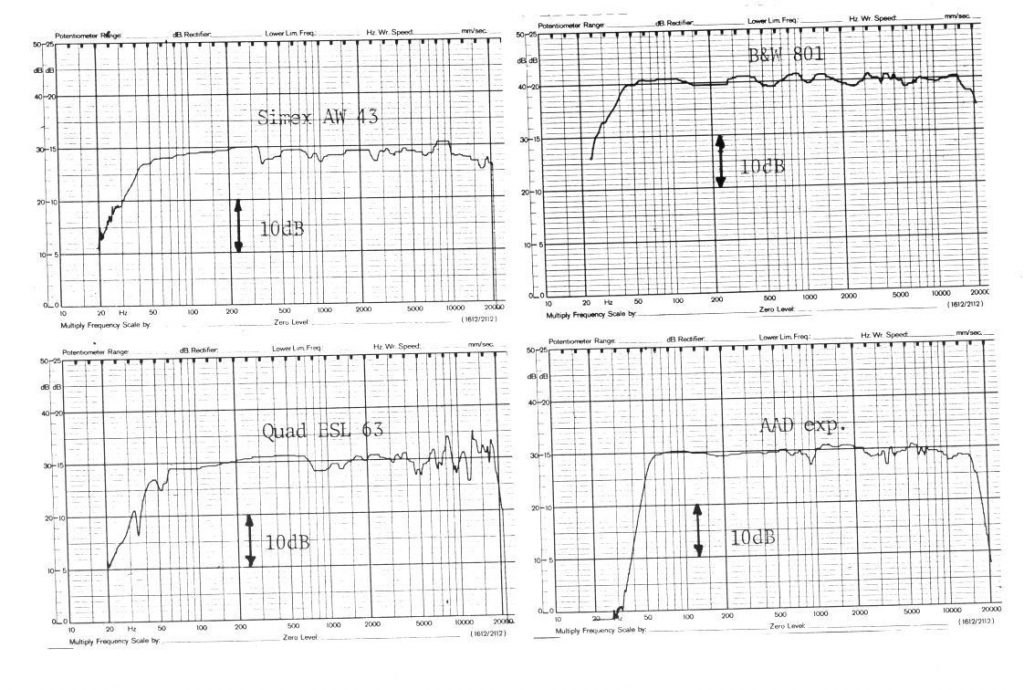

The test concerned a listening test made in an anechoic chamber (as shown in the illustration below). The switch enabled the AB test between the loudspeaker-microphone combination in the echoless room outside the anechoic chamber and the straight wire. Before listening, the levels of A and B were adjusted equal. The microphone was B & K 4133 and it was located on-axis. After listening, the loudspeakers were measured with the same microphone set (the second figure shows measurement results of some of the speakers in the test).

Furthermore, Salmi and Weckström explored both objectively and subjectively, the effect of the room on the tone of the sound and the coloration of the sound by simulating the early reflections from the nearby surfaces. The test signal was mainly pink noise. The same signal was added to itself delayed by an adjustable delay line. Using the AB test (delayed signal added or not), and different delay times, the level of the delayed signal was determined in which the difference was just about audible. The ear seemed to be the most sensitive for <2ms delays. As the delay increased, the sensitivity gradually deteriorated. The same phenomenon was also experimented with music. A broadband signal (eg. a big orchestra) was almost as good as noise, but more time was required for detecting it.

The conclusion drawn from the experiment was obvious: in an anechoic room speakers with a smooth free-field response, regardless of the brand, sounded pretty good and not too dissimilar between each other. Under ”normal” circumstances, these “well-designed” speakers sounded colored and mutually different. Thus, the colored tone of the sound had to result from the room interaction. No question about that.

What Gradient, with these experiments, wanted to convey to the field of loudspeaker manufacturing, was that when we listen to a loudspeaker, what we actually hear is, to a large extent, room reflections, and when we listen to the reflections, what we’re actually listening is more or less the frequency response measured at the listening position, and nothing else.

And what about other possible factors affecting the sound quality? Cabinet resonances, distortion, phase shifts and many other sound deteriorating causes? It would be wrong to say that Gradient did not care about them, but their effect on the whole has always been secondary to Gradient as compared to the influence of the room.

From this theoretical and empirical work began Gradient’s “ferocious” struggle against the room and its sound-spoiling effect. That battle has got more sophisticated forms (such as the cardioid solutions) later and is still going on.

Salmi and Weckström were not the first, nor the only speaker designers who were concerned about the room effect. However, unlike other manufacturers who also commented on the subject, Gradient and Salmi took the matter further, consistently and stubbornly to its logical end.

To Gradient’s big surprise, the situation in the loudspeaker market did not substantially change after the introduction of the Gradient 1.2 or 1.3. The corrective measures of other speaker manufacturers continued to be fairly conventional. Just in recent years, with the emergence of digital room correction and dsp technology, the situation has somewhat changed. There’s a difference though. Those using digital technology try to remedy the flaws of their designs electronically, whereas Salmi/Gradient aims to attack the problem before it occurs on the level of basic loudspeaker design, by making their speakers less sensitive to the room influence in the first place.

From zero to three

From zero to three

The first 1-series Gradient was Gradient 1.0. It was manufactured in 1984. Even before that, Gradient tried to satisfy the demand coming from it first customer: the Sibelius Academy of Music.

In the following year, 1.0 was replaced by 1.1 the changes being mainly mechanical. The upper part of the supporting arm was now made of flat iron, and the ends of the tweeter housing were now tin plate instead of “easily dropping plastic bags”.

In 1987 the 1.2 was published with entirely different tweeter elements (the old ones were no longer available). The new tweeter was one designed by Knud Thorborg for Peerless in the early 50s, and had a deeper cone profile. At the same time, the grill in front of the treble tower was redesigned in order to remove standing waves from between the grill and the tweeter cones.

According to Salmi, the crossover of the 1.0 and 1.1 sported a cap in series with the woofer, to extend the loudspeaker’s bass response even though the fall behind the resonance frequency was then steeper. However, all the amplifiers of the period did not stand such a load, and the cap was removed from the 1.2.

The cone of the original midrange driver was discontinued in 1988. At first Gradient used an Audax driver as the replacement, but soon began to develop a new better sounding one together with Peerless. The 1.3 was already under development. The last individuals of the 1.2 shared many parts with the 1.3 such as the new Peerless midrange unit, and the new aluminum profile for the tweeter column. In the autumn of 1989, the 1.2 was finally discontinued and made way for the 1.3 with the polyurethane cylindrical woofer cabinet with the 20mm plywood bottom plate.

The cone of the original midrange driver was discontinued in 1988. At first Gradient used an Audax driver as the replacement, but soon began to develop a new better sounding one together with Peerless. The 1.3 was already under development. The last individuals of the 1.2 shared many parts with the 1.3 such as the new Peerless midrange unit, and the new aluminum profile for the tweeter column. In the autumn of 1989, the 1.2 was finally discontinued and made way for the 1.3 with the polyurethane cylindrical woofer cabinet with the 20mm plywood bottom plate.

The 1.3 was manufactured till 1997. It was Gradient’s first export model. As such, it received an excellent reception in many countries, including the US where eg. The Absolute Sound praised it loudly.

Gradient 1.3 and the fight against the room

So what explains the design of the Gradient 1.3?

Whatever it was going to be it had to meet certain criteria: early reflections and especially the floor reflection had to be cancelled at all cost; the direct and the reflected sound had to be as far apart as possible in the time domain; and the free field/power response as smooth and uniform as possible. Also, the loudspeaker should sound good in the widest possible area.

These goals, Salmi/Gradient set off to obtain a frequency band at a time. To undo the floor reflection and limit the radiation at bass frequencies, Salmi did what Snell had done earlier with the Type A speaker: made a reflex-tuned 8 inch woofer shoot directly to the floor from a distance of a few centimeters. In this way, in the frequency range of the woofer, the direct and reflected sound are practically in the same phase, and there is less energy available for the room to cause problems.

For frequencies up from the 250Hz crossover point, Salmi chose a 12 inch dynamic driver without an enclosure. With the figure 8 radiation pattern, the driver directs the sound to both directions, front and rear, but not to the sides, the directivity increasing toward the highest frequencies. Due to the short circuit at the lowest frequencies of the midrange driver, the upper end of the spectrum had to be electronically equalized to keep the response smooth. The driver is angled 30 degrees to eliminate the floor reflection.

The tweeter is a line source with four 1.4 inch cone tweeters in a sealed box. The tweeter column takes the responsibility for the sound reproduction at frequencies higher than 1500 Hz and are thus EQ’ed that the response stays even and the directivity constant up to the highest frequencies.

Harmonizing radiation patterns and keeping the power levels smooth from the three completely different cabinet solutions, especially around the lower crossover point, proves Salmi’s design skills and pragmatic approach. To keep the sound uniform and integrated from the down-firing bass and open back midrange driver Salmi trusts the low crossover frequency (vis-a-vis the mutual distance/wave length), and the diffused sound-field so that whatever directivity differences there may be, they are effectively masked. The power response has been made smooth by choosing the right mutual level for the bass and middle area element.

Airy, non-box sound

There are speakers that work in theory but not in practice. There are other speakers that work in practice despite the dubious underlying theory. Salmi is known for speakers (eg. Helsinki) whose background theory is solid but does not unobtrusively show that the speakers would also work de facto. But they do.

To me the 1.3 was once such a ear-opening revelation that my old B&W floorstanders got their heads off. I can not remember that I would ever have had any frequency-band related problems with the 1.3. Some people complained about the protruding treble but I never quite understood what the accusation was all about. The bass too was quite excellent given the smallish volume (20L) of the cabinet.

Personally the most significant new feature that the sound of the 1.3 brought on was how magically the speakers disappeared. Especially in the beginning the 1.3’s airy and open and non-cabinet-like sound was really impressive and very, very addictive. It’s still a fascinating feature of its sound. Especially with recordings that contain plenty of well-recorded spatial information, the speaker is unbeatable. The sound is not just airy and spacious, it’s also plain and genuinely stereophonic.

When one gets a chance to hear the direct sound to this extent, in relation to the reflected sound, experience is new and fascinating, but also a bit confusing. Many recordings sound as if something was missing from the sound. The sound is “different” and so peculiar that it raises the question whether the price paid for the amazing disappearance of the speakers and the magnificent airiness of the sound has been too high? Has the battle against the room gone a step too far?

Axioms and theorems

A friend of mine, who’s got both the 1.2 and Dali monitors, once pointed out to me, without explaining it any further, that to his ears the Dalis sounded more pleasing. I do understand him. The question is not whether Dali’s modern dome tweeters would reproduce the highest harmonics so much more beautifully than the paper cone tweeters of the 1.2, even though there certainly is a difference in tone between the two.

I’d say the difference had more to do with the fact that the Dalis performed and sounded like loudspeakers usually do: predictably and soaking up support and color from the room. Many recordings are enriched with fullness and mellowness in this way, and the result may sound pleasing even if the sound itself is not completely clean and uncolored.

By Gradient’s criteria – the amount of direct sound and non-speakerlikeness – Dalis have no chance. But is the unattached and airy sound or even the absolute colourlessness everything?

Here we come to an interesting question about theories and their basic assumptions, that is, the axioms. An axiom is a claim that the theory takes as true, for example simply because it is considered obviously true. Other propositions made within the theory follow from the axiom(s).

I would not argue with Salmi about the way he has developed his basic claims from the initial assumptions. Nor would I doubt the conclusions he has drawn from his theory. Flawless.

But no loudspeaker manufacturer, including Gradient, can tell other manufacturers to share the same axioms. Gradient’s starting assumption has unquestionably always been that the recordings ought to have all the required information (spatial and other) stored on them, and that the function of the loudspeaker is just to reproduce the material on a disc, as it was originally recorded, without the speaker or the room interfering it or at least interfering as little as possible. The Gradient 1.3 with wealth of direct immersive sound is the kind of loudspeaker.

Another loudspeaker manufacture may, however, choose different assumptions though, for example that majority of acoustic recordings (studio productions are a different story) do not contain enough reflected sound, and therefore conclude that partial omni-directionality of the loudspeakers, and some reflections from the room, are not entirely harmful. Speaker cabinets are in such listening revealed, but the sound from various recordings may be more pleasant and sensible than without the support of the room.

Not unrelatedly, I have been sitting in several professionally acousticated listening rooms the treatment costing tens of thousands euros, where reflections are pressed to a minimum and the reverberation times optimized, and where the sound in itself has been just fine, but yet somehow unnatural (with music) to my ears.

The difference in default assumptions is important, but should not be over-emphasized. Dali monitors are just fine for playing back remotely recorded (with a single microphone pair) recordings. The Gradient 1.2 and 1.3 can reproduce studio material on a large scale though some tracks may sound a bit special.

The rationality of the heart

The rationality of the heart

One of the milestones of my hifi career was an Audio Fair in Paris in 1994 or 1995. I was walking around the Le Palais de Congres, passing from one room to another, until I arrived in one where the sound and the speakers were as if from a different reality. The speakers were prominent and clearly visible, but the sound and they did not seem to have anything to do with each other. I was totally stuggered! The Fair had some electrostatic loudspeakers and other speaker designs with higher than average directivity, but none came even close to this. The speakers in point were, or course, the then new Gradient Revolutions.

It wasn’t long that the Revolutions replaced my 1.3s in my home system, and they too were in house for an exceptionally long period of time. Having owned both of them, which one is better? The question is not stupid even though the Revolutions cost twice as much as the 1.3. The 1.3 has its own attractive features, of which the delicious 2.5 octaves between 250-1500Hz is not the least significant. It is clear, however, that Revolutions, in addition to their tight, but not heavy, dipolar bass, carry out the Gradient’s sound-ideal even more faithfully than the 1.3.

Which one do I miss more? Not an easy question. The Revolution is more of a technical achievement and in that sense, also more neutral in terms of the emotions it evokes. The sympathetic 1.3 is an easier case to associate with. With the 1.3 one doesn’t have to sit still and serious in one corner of the stereo triangle, nor constitute one’s self-image as an earnest hifi enthusiast. With the Revolutions the attitude is more professional. That’s why it is possible that if the heart were to choose, it would be the 1.3, the Revolution being the favorite of the reason.

In Finland at least people are pretty well aware of how a high-quality speaker the 1.3 is, which is why the used pairs of the 1.3s do not spend long in the second hand shops. One obvious reason for their scarcity on the second hand market is the timeless design.

The best known Finnish loudspeaker world-wide is probably Genelec. However, as compared to Gradients, Genelecs represent quite traditional and unimaginative implementations (apart perhaps the latest One series).

For me, the Gradient 1.X is the most iconic Finnish loudspeaker – by a large margin.