”If there is to be a definition of art that fits contemporary art as well as all previous art, it has to be consistent not only with the fact that there are no limits on what can be art but also with the possibility that artworks and mere objects can resemble one another to any degree whatever” (Danto 1999, 8).

In his first major one-man exhibition in Europe, On the Other Side of the Borders (“Jenseits der Grenzen”) at the MAK (“Museum für angewandte Kunst”) in Vienna in 1996, Burden exhibited his “Flying Steamroller” which was kept in the air by a counter-weight of 40 tons. Unfortunately the 12 ton steamroller was lifted into the air only every second hour instead of every two minutes as the Burden originally wanted. By this limitation the show did not match the machine concept which the artist had in mind. When Burden’s “Flying Steamroller” was part of the 1997 Lyon Biennale, the steamroller was made to ‘fly’ correctly by a mechanical system which included a counter-weight of 16 tons. It was a favorite with the audience (Haase 1997).

The piece demonstrates nicely just how unlimited art can nowadays be. In an interview with Johanna Hofleitner, Burden is convinced that art has an impact on how people think (Kunstforum, 134, May-September 1996, pp.336-345). He sees himself “more like” a scientist or an experimental researcher with a strong interest in problems such as what is art, and how is art related to the real world, to life, to our perception.

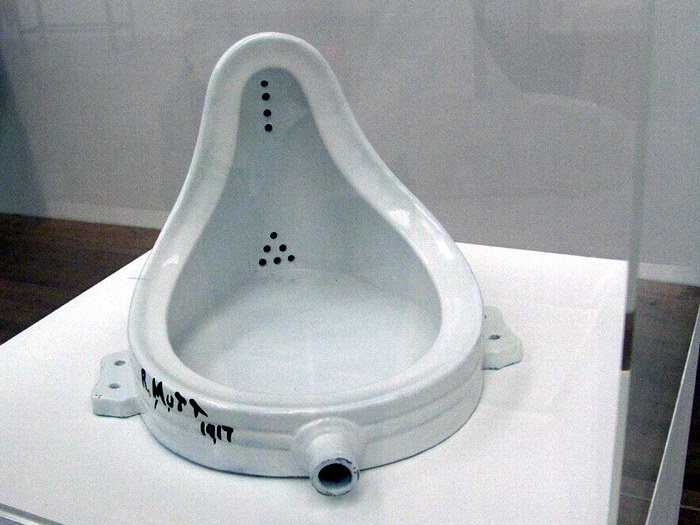

Burden isn’t of course the only contemporary artist who’ve participated in the ongoing dialogue of the artists with the concept of art. In 1995 April, the Hamburger Kunsthalle (Museum of Fine Art) exhibited a white earthenware and heavily damaged urinal entitled Ghost Falling Down the Staircase (“Gespenst die Treppe herabstürzend”) by a German artist of the name of Klaus Kumrow. The piece is an obvious reference to Marcel Duchamp’s The Fountain while the title points to Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (“Nu descendant un escalier”) which was first exhibited at the Amory Show, New York, in 1913. Kumrow’s Ghost, just like Burden’s Steamroller, demonstrates the substantial inertia in this dialogue with the concept of art as it took a while before the art world was aware of the dialogue. No doubt, earlier works of art also raised these questions but it is fair to say that at least in the view of conceptual artists, the discussion was dominated by formalistic issues: problems of color and form, perspective, representation, etc.

Marcel Duchamp is often credited for raising the function of art as a question and defining it as its content of art, thus “giving art its own identity”. “With the unassisted Readymade, art changed its focus from the form of the language to what was being said. Which means that it changed the nature of art from a question of morphology to a question of function. This change – one from ‘appearance’ to ‘conception’ –-was the beginning of ‘modern’ art and the beginning of ‘conceptual’ art. All art (after Duchamp) is conceptual (in nature) because art only exists conceptually” (Kosuth 1974, 146). “The ‘made-ready’ and the tradition of the readymade has shown us what the process of art is; the path of that showing has meant the development. through its self-reflection, to the critical location of an ideological self-knowledge; this alternative tradition sees art, simply put, as a questioning process” (Kosuth 1991, 18). Here the “made-ready” is the constructive appropriation of the object which is a precondition such that the process of art is accountable and demystification is possible. “The practice of the ‘made-ready’ has clarified, within its constructions, how specific elements (or forms) used within art, as within language, are by and large arbitrary; the sense can only be understood in the systematic whole. And it is such a systematic whole that not only makes possible the production of further meaning, but joins the viewer/reader and artist author within a social whole as well” (Kosuth 1991, 23). This, of course, also holds for the unassisted readymade.

Duchamp’s readymades entered the art world through the reactions of his fellow artists, the art critics, and the public. Following Duchamp’s path, in the second half of the 1960s, some artists no longer sought dialogue with the art audience but with art itself. Art is a very complex and demanding partner and one that is not always very spontaneous in its reaction. The dialogue is also not without complications. Moreover, the objects of the dialogue are ideas and the regular art audiences –- museums, galleries, collectors and art critics –- had to rest content with traces of them since objects were seen as conceptually irrelevant to the condition of art. Often these traces were words which are difficult to hang on walls. I am talking about conceptual art which is seen as an inquiry into the foundations of art. Its content is to question the nature of art. By this, Joseph Kosuth (1974, 148) claims, “art ‘lives’ through influencing other art, not by existing as the physical residue of an artist’s ideas”. “The ‘value’ of particular artists after Duchamp can be weighed according to how much they questioned the nature of art; which is another way of saying ‘what they added to the conception of art’ or what was not there before they started” (Kosuth 1974, 146). There is a potential of conceptual growth in this definition.

Creation, Creativity, and Style

The use of readymades as art naturally challenges the notion of the artist as creator which is widely shared by the audience. However, it also concurred with the focus on creativity (or originality) as one of the core principles of Abstract Expressionism. Oscar Wilde summarizes this view in his Preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray: “The artist is the creator of beautiful things”. By creation it is meant something new, something which did not exist before. Wilde was a proponent of aestheticism and to him “living” meant “living beautifully, down to the last detail. Despite its apparent superficiality – or indeed, because of its apparent superficiality – the insistence that every aspect of lived life be exquisite and unconventional was part of a philosophical and artistic project of subversion” (Mendelsohn 2002, 18).

The Middle Ages lacked a concept of beauty as a general principle and an idea of the artist as creator: the creation was God’s work with the result that the fine arts did not exist. In the tradition of Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas made a distinction between the servile and the liberal arts: manual arts were servile, and the superiority of the liberal arts was due to their rational subject-matter and their being arts of mind the rather than the body. The belief in the inferiority of manual activity and the low social status of the artist in these fields are most likely the result of the verdict that the artist can make new compositions, but he cannot make new things. Only God– and Nature under God’s Law –can create new things: “The artist can help or hasten the productive rhythm of nature, but he cannot compete with it” (Eco 1986, 96). Not surprisingly, this view has an echo in Marcel Duchamp’s perspective on art as a craft. He “denounced the superstition of craft. The artist is not the maker of things; his works are not pieces of workmanship – they are acts” (Paz 1978, 23). Duchamp’s readymades are a straightforward consequence of this view.

In the middle ages, beauty had not yet been discovered as a general principle for characterizing art (at least in some periods), although there were clearly pioneers in this direction. St. Bonaventure (1217 (1221?) -1274), for instance, “distinguished two reasons for the beauty of an image, even when the object imitated was not beautiful in itself. An image, he said, was beautiful if it was well constructed, and if it faithfully represented its objects” (Eco 1986, 102). It should be noted that at the time of St. Bonaventure, angles and devils were common objects of representation. One need only look at the great works of Giotto (1270? – 1337), the Tuskan father of art, and his Roman “rival” Pietro Cavallini (1250? – 1325?). The question is, then, what guaranteed their faithful representation? Tradition, style, or the words of the Scripture?

If there is no creation in art, can there be progress? Paul Feyerabend (1984, 29) remarks: “There is no progress in art, but there are different styles and each style is perfect in itself and follows its own law. Art is the production of styles and art history is the history of their sequence”. Here, Feyerabend draws on Alois Riegl’s work on the Late Roman art industry and his interpretation. In his book on the Spätrömische Kunstindustrie, first published in 1901, Riegl (1973 [1901]) analyzes the early Christian art which is widely considered as a rather primitive imitation of the art of antiquity – cleansed of some of the characteristics which are thought to contradict Christian ideals. However, the critics overlooked that the early Christian art reveals a completely different understanding of the representation of space than in antiquity, a fact which is later most eminently amnifested in the gothic cathedral. This understanding necessitates a more isolated presentation of figures in space which often violated the proportionality of figures in size, shape and position to each other. This is not a decline, but change of style.

Le Style c’est l’homme (méme). (“Style is man himself.”) There are many interpretations to this quote made by the 18th century natural scientist Comte de Buffon. The definition has often been wrongly taken to mean that style is a personal idiosyncrasy to be cultivated deliberately. But as Heinrich von Stein (1857-1887) claimed, Buffon is to be understood in general and not specific terms: The human dimension lies in the stylizing of the material, in giving material a style, in its “rational presentation”, and not just in collecting it (see Wölfflin (1984 [1905]). Style is characteristic of human productions at their best, not something to be added as an ornament. In his Discourse on Style (1753), delivered on his admission to the Academie Francaise, Buffon protested against the artificialities of the day, in favor of a simple direct manner, suitable for intelligent communication. Can we classify Duchamp’s readymades and the “made ready” à la Kosuth as a farewell to artificialities?

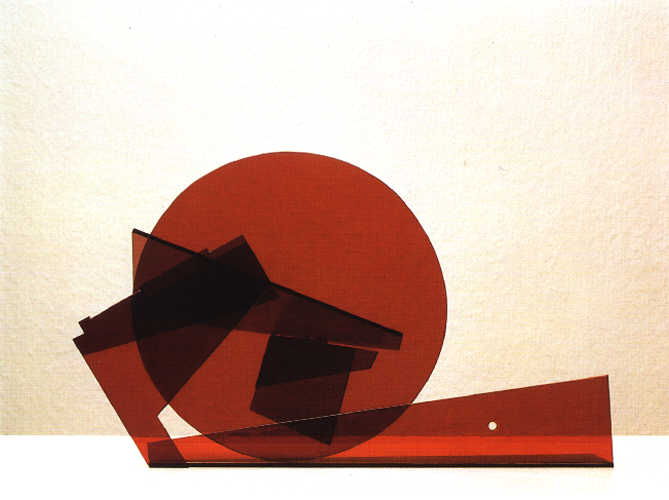

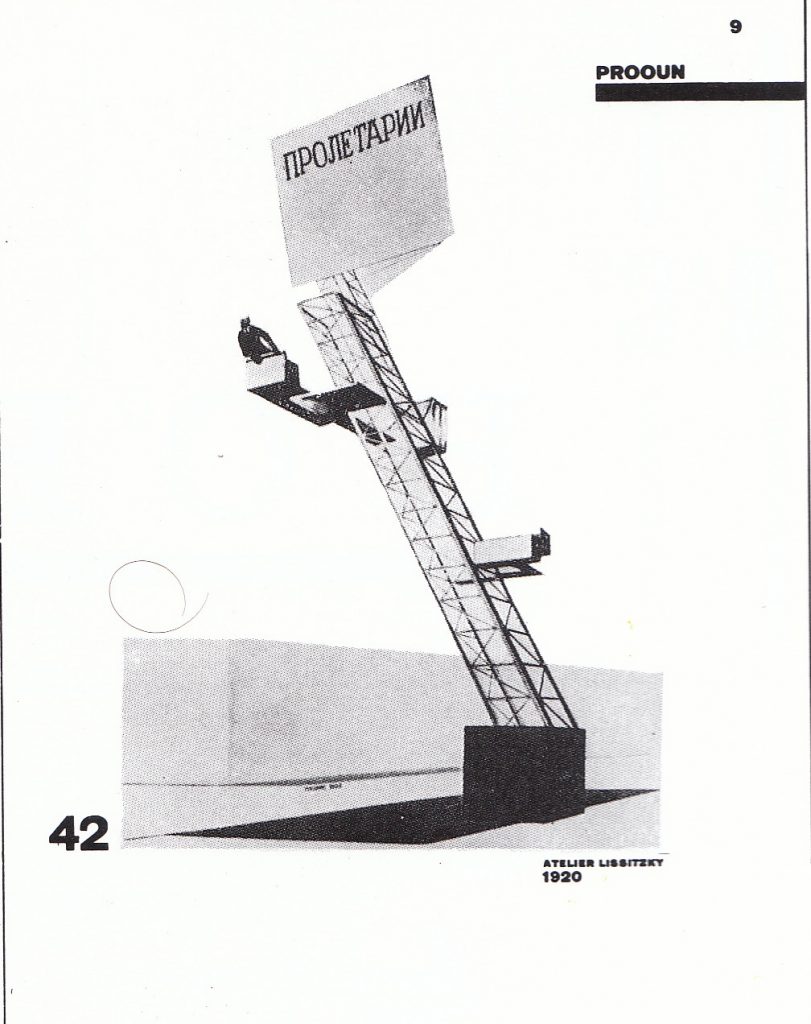

In his recent book, Paths to the Abolute, John Golding points out that, in a special sense, Mondrian, Malevich,and Kandinsky accepted nature as object to be “made ready.” They drew inspirations from science and from various kinds of mystical thought. Kandinsky was particularly interested in the ‘fourth dimension’ and in Theosophy. Malevich was obsessed by the scientific and mystical properties of geometry. Mondrian “sought an art that would give expression to a higher order of reality by transcending subjective experience and eliminating what he called the ‘tragic’ from his painting” (Flam 2002, 12). The abstract expressionists of the 1940s and 1950s, i.e. the painters of the New York School, considered painting as a means to discover nature. Robert Motherwell’s psychic automatism implied that painting started with a process of “doodling” or scribbling – it “really was what the hands did, acting on their own” (Danto 1999, 30). It was a method to abandon consciousness and to find out what is there: Nature.

When Jackson Pollock was asked why he did not paint from nature, he famously responded, “I am Nature.” “Painting is self-discovery. Every good artist paints what he is.” (quoted after Flam 2000, 12).

* This material for this article derives from Holler (2008).

Danto, Arthur C. (1999): Philosophizing Art: Selected Essays, Berkeley. University of California Press.

Eco, Umberto (1986): Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages. Translated by Hugh Bredin, New Haven and London. Yale University Press.

Feyerabend, Paul (1984): Wissenschaft als Kunst. Frankfurt. Suhrkamp-Verlag.

Flam, Jack (2001): Review of ‘Paths to the Absolute: Mondrian, Malevich, Kandinsky,

Pollock, Newman, Rothko, and Still by John Golding’. New York Review of Books 48, (April 26), 10-14.

Haase, Amine (1997): Panik in der Kunstwelt, Kunstforum 138 (September-November), 254-269.

Holler, Manfred J. (2008): Re-defining Arts, Readymades and Secrets. Homo Oeconomicus 25 (in print).

Kosuth, Joseph (1974): Art after Philosophy, in: G. de Vries (ed.), Künstlertexte zum veränderten Kunstverständnis nach 1965. Köln.

Kosuth, Joseph (1991): No Exit. Ostfildern /Stuttgart. Edition Cantz

Mendelsohn, Daniel (2002): The Two Oscar Wildes. New York Review of Books 49, (October 10), 18-22.

Paz, Octavio (1990): Marcel Duchamp: Appearance, Stripped, Bare. New York. Arcade Publishing.

Riegl, Alois (1973 [1901]): Spätrömische Kunstindustrie, Darmstadt. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Wölfflin, Heinrich (1984 [1905]): Die Kunst Albrecht Dürers (Preface to the1st Edition, reprinted in the 9th Edition). Munich. Bruckmann.